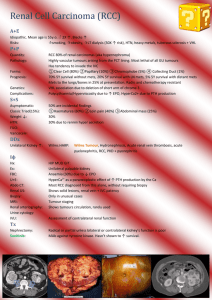

Renal & ureteric neoplasms

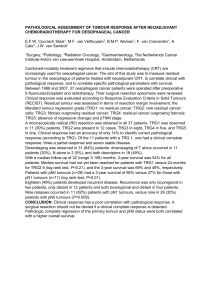

advertisement