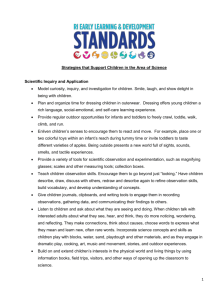

early intervention guidelines for infants and toddlers with visual

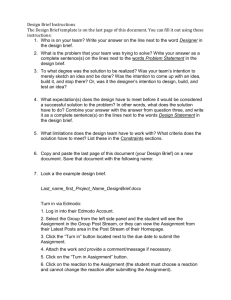

advertisement