EN 101 Lesson 9 – 10

advertisement

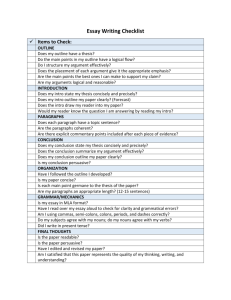

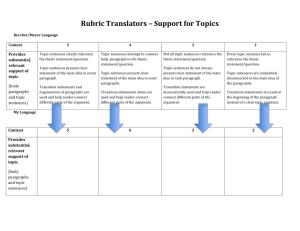

Lessons 9-10: Constructing an Argument and Writing Precise, Concise, Consistent, and Sophisticated Paragraphs Lesson Objectives: o Reinforce the six steps of the writing process. o Discuss in detail the development of effective arguments built around precise, concise, consistent, and sophisticated paragraphs. o Examine the attributes of an effective thesis, fully developed paragraphs, and the fundamentals of argumentative writing. o Briefly address how to identify and rectify comma splice, fused sentence, and pronoun reference errors. Texts: o Lesson 9: o “Writing an Argument,” LBH 211-228 o “Comma Splices and Fused Sentences,” LBH 360-366 o TS/IS – Chapter 5. o Lesson 10: o TS/IS – Chapter 6. o “Writing and Revising Paragraphs,” LBH 79-109 o “Pronoun Reference,” LBH 367-373 Pedagogical Intent: This two-lesson block reinforces the six steps of the writing process (ideation/brainstorming, outlining, drafting, editing, revision, publication) before focusing more precisely upon constructing effective argumentative essays and precise, concise, consistent and sophisticated paragraphs. These lessons are critical as cadets engage in the writing process with an eye towards publishing their draft HWE 1 at the beginning of Lesson 13. Lesson Plan: o Address issues/questions remaining from the previous class and the lesson assignment. o The six steps of the formal writing process: o Ideation/Brainstorming o Outlining o Drafting (x 3) o Editing o Revision o Publication o A few notes about paragraphs and arguments. o A paragraph: Is an indented group of sentences set apart from other groups of sentences. Helps organize ideas. Indicates key changes in the argument. Introduces main points of your arguments. Develops evidence in support of your main points. Form the different elements of your argument. Introduction (and thesis). Body paragraphs (sequentially address the main points of your argument). Conclusion. o What are the ELEMENTS of an effective paragraph? Effective paragraphs are unified, coherent, and fully developed. Unified Paragraphs: Explore 1 and only 1 idea. Introduce and strictly focus upon a clearly stated topic sentence. TIP: Try highlighting the topic sentence in every paragraph you write. Then check each sentence in the paragraph. Does each sentence DIRECTLY support the paragraph’s topic sentence? If you cannot identify your topic sentence – or have added sentences that do not directly support the topic sentence – then you probably have not constructed a unified paragraph. (Stated a bit differently. If you cannot identify your topic sentence, how can you expect a reader to do so?) o Coherent Paragraphs: Are organized precisely and concisely. Achieve effective organization in accordance with the following patterns: o Spatial: Within a specific space or place. o Chronological: Within a specific time frame. o Specific to General: Show how specific instances lead to more general observations. o Problem-Solution: Identify a specific problem…and its solution. o Climactic: Construct building blocks leading to a climax. Employ effective diction: o Precise. o Concise. o Consistent. o Sophisticated. Employ effective transitions. o Fully developed paragraphs: Provide evidentiary support (evidence). o Quantitative evidence (numbers, statistics, figures, etc.) o Qualitative evidence (quotes, quotations, facts, etc.) Implement a strategy. (Pattern of Development) o Description. o Illustration/support. o Definition. o Division/analysis of the parts. o Classification. o Compare/contrast. o Analogy. o Cause and effect. o Process analysis. Paragraph length. o General rule: Between 5 and 8 sentences. o Any shorter than 5 sentences the paragraph usually lacks development. o Any longer than 8 sentences the paragraph usually lacks unity, precision or concision o An argument: Is both a process and a product. Requires justification of its claims. Combines the pursuit of truth and persuasion. Is a rational inquiry. o The essays you will write in this class will rely upon argumentative writing. You will propose a thesis. (“This is what I think and this is why I think it.”) You will then support that thesis with evidence and analysis. AND you will do so in a precise, concise, consistent, and sophisticated manner. What is a thesis statement? o Your thesis is your argument’s main idea, its central, dominant, and focusing point. Quite simply – your thesis is the point you are trying to make with your argument. o Your thesis makes a stand. It says (figuratively) – “This is what I think and why I think it.” o An effective thesis statement: Is reasonable and relevant. Narrows your argument to a single, specific, and significant central idea. Concisely and precisely states this main idea. Accurately reflects your essay’s purpose while being: Expressive Informative Persuasive. Establishes your voice. Must be concisely and precisely worded: Your thesis must be your essay’s most effective sentence / statement. Your thesis should be able to stand alone. Your audience should know exactly what the essay is about from reading this one statement. Do not use vague or imprecise diction/language. Do not confuse your audience with irrelevant or complex terminology. Keep it simple, effective, and thorough. After developing your thesis, you must identify the main ideas you will use to support your thesis. o Do not limit yourself to three main ideas simply to fit the “traditional” five paragraph essay. If you need only two ideas to support your thesis, that is all you need. If you need five main ideas, well – that is how many you should use. o Identify topic sentences you intend to expand upon in the essay’s body paragraphs. What is a topic sentence? The topic statement is, in effect, a thesis statement for a paragraph. It tells your audience exactly what you hope to accomplish in the paragraph. Do not bite off more than you can chew. Break down your argument into enough main ideas that you can precisely, concisely, and consistently support your paragraph’s topic sentence in a paragraph of approximately 5-8 sentences. You should now have the fundamental basis for your argument: o Your thesis. o Your main points you will use to support your thesis in sentence format. o The specific topic sentences you will use to “prove” those points. So, now let’s turn to how one supports an argument with evidence and inductive and/or deductive reasoning. o Claims are “positive statements that require support” (LBH 177). o Evidence includes “the facts, examples, expert opinions, and other information that support the claims” (LBH 177). Statistics, quoted material, verifiable statements of fact, etc. When writing in response to specific texts, as we do in this class, the most persuasive evidence often comes directly from the source material – the readings themselves. Evidence must be: Accurate Relevant Representative Adequate. o Assumptions are “underlying (and often unstated) beliefs, opinions, principles, or inferences that tie the evidence to the claims” (LBH 178). You must avoid common fallacies or “errors in argument” – evasions and oversimplifications. o Evasions – your thesis and subordinate claims must not avoid or dodge the issue you are addressing. Common evasions include: Begging the question – treating, accepting, or offering opinion as fact. Non-sequitur – does not follow – the conclusion does not reasonably follow from the evidence presented – or the evidence is irrelevant. Distracting through the introduction of a “red herring” – introducing an irrelevant issue to distract the reader. Relying upon a false authority – including evidentiary support from an “expert” who is not really an expert in the field in question. Using an inappropriate appeal – ad hominem, ad populum, etc. o Oversimplifications: Common oversimplifications include: Hasty generalizations that jump to a conclusion without providing specific support. Broad, sweeping generalizations – stereotypes, etc. Reductive fallacy – oversimplifies the relationship between a cause and effect. Post hoc fallacy – Because A precedes B, A caused B. False dilemma – reducing a complex issue to either A or B. False analogy. Strong and effective argumentation often relies upon both inductive and deductive reasoning. o Inductive reasoning relies upon specific observations about evidence to induce or infer a claim. Evidence – Assumption - Claim Inductive reasoning “builds from the evidence to the claim, with assumptions connecting evidence to claim” (LBH 200). Inductive reasoning essentially “predicts something about the unknown based on what you know,” thereby “creat[ing] new knowledge out of old” (LBH 200). Absolute certainty is not possible with inductive reasoning alone. Using inductive reasoning: State your evidence clearly. Ensure your evidence is complete enough and strong enough to justify your claims. Clearly state the assumption that connects the evidence and claims. Ensure you avoid common fallacies. o Deductive reasoning proceeds from an assumption thru evidence to make a claim. Assumption – Evidence – Claim. Deductive reasoning often relies upon a syllogistic form: Premise 1: A generalization, fact, principle or belief leads to: Premise 2: New information or a specific case of the first premise which leads to: Conclusion. As long as the premises are true – the conclusion should be true. Using deductive reasoning: Clearly state your premises. Identify exactly what the first premise assumes. Ensure all premises are believable. Ensure the first premise leads directly to the second premise. Avoid common fallacies. Evidence: Effective, convincing evidentiary support: o Does not distort, exaggerate, or twist facts, statistics, etc. simply to fit the argument. o Does not ignore facts, statistics, etc. that oppose or undermine the argument. You will need to address these opposing facts; you cannot simply ignore them. o Does not oversimplify the issue. o Does not misquote primary sources. Organizing an effective argument: o Baseline: Intro – Body – Response to Opposing Views – Conclusion o Modifications: Intro – Claim 1 and Evidence – Response to Opposing Views on Claim 1 – Claim 2 and Evidence – Response to Opposing Views on Claim 2 – Claim n and Evidence – Response to Opposing Views on Claim n – Conclusion Intro – Common ground and Response to Opposing Views – Claim 1 and Evidence – Claim 2 and Evidence – Claim n and Evidence – Conclusion Intro – Analysis of the problem/issue with claims and evidence – Pose a solution with claims and evidence – Response to Opposing Views – Conclusion TS/IS – Chapters 5 and 6 o Chapter 5: You must ensure your readers can distinguish between what “you say” and what “they say”. About the use of the first person – “I” or “we” o Usually, in formal academic writing, we try not to use the first person except in situations where its use might be particularly persuasive or applicable. o The narrative pattern of development, for example, is often quite persuasive in an introduction or conclusion. You use a personal narrative to introduce a subject, to provide context, or to show how it is specifically pertinent to you/your life. Then you move on to the other rhetorical strategies (compare and contrast, definition, exemplification, classification and division, etc.) for the remainder of your argument. o Ultimately, the argument against the use of the first person is not that “I” is necessarily bad – but that it tends to diminish the universal appeal of one’s argument. Removing oneself from one’s argument tends to broaden its appeal. o Graff and Birkenstein contend “I” can be very persuasive. While their point that “well-supported arguments are grounded in persuasive reasons and evidence, not in the use or nonuse of any particular pronouns,” is compelling, we nevertheless tend not to use “I” in formal, academic writing (72). o This does not mean that G & B’s templates are useless. Rather, they are very useful. Use them – and the first person – in your initial drafts. Then edit/revise your essay and either eliminate (or use) the first person based upon a conscious decision. o Bottom Line: If you choose to use the first person, do so only after carefully considering the rhetorical situation and your intended audience. G&B identify “embedded voice markers” (see 74-75). o “Embedding” references to those who oppose your argument informs your reader not only about your opponent’s position but also that you have dealt with the opposing viewpoint – thereby distancing your argument from “theirs.” Chapter 6: You must address a counterargument – what critics of your argument might say about your argument. o Critics might suggest ______; however, ____________. o Though critics might argue ___________, _____________. Anticipate objections to your argument. Incorporate these objections into your argument and then counter them. This reinforces the idea that you are engaged in a scholarly conversation. Be specific when responding to objections – identify / label those who criticize your argument…but do so objectively, without apparent judgment and specifically identify and respond to relevant objections. Templates 84. Add quotations from your critics – and then respond directly (and fairly) to those quotations. There is nothing wrong with conceding one or two points – but you must still hold your ground. Template – 89. Comma Splice: Fused Sentence: Pronoun Reference: Lesson 11: Writing Introductions and Conclusions and Writing Workshop o Complete preliminary draft for HWE 1 o Read “Writing Special Kinds of Paragraphs,” LBH 110-116 o Read TS/IS – Chapter 7 (92-101) o Study “Shifts,” LBH 374-379.