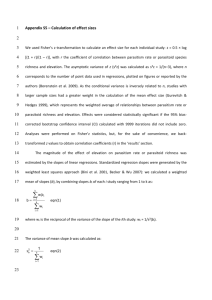

Excerpts-from-the-Rosenberg-Trial-Transcripts

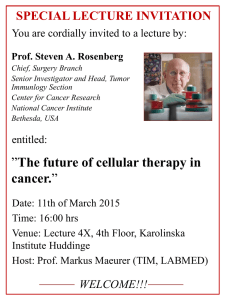

advertisement