Agentic and Affiliative Extraversion: A

Running head: AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 1

Agentic and Affiliative Extraversion: A Psychometric Study

_____________________________________

A Thesis

Presented to

St. Thomas University

____________________________________

In Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Certificate of Honours Standing in Psychology

____________________________________

Lauren Morrissey

April 2013

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 2

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................3

Abstract............................................................................................................................................4

Introduction.....................................................................................................................................5

Method...........................................................................................................................................17

Results............................................................................................................................................20

Discussion......................................................................................................................................22

References......................................................................................................................................29

Appendix A....................................................................................................................................35

Appendix B....................................................................................................................................40

Appendix C....................................................................................................................................41

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 3

Acknowledgements

The completion of this thesis was not something I was able to accomplish on my own. I would like to express my thanks and gratitude to Dr. Michael Houlihan, my thesis supervisor.

This would not have been possible without your guidance, and I truly appreciate you allowing me to complete this study. Second I would like to thank Dr. Mihailo Perunovic, the reader of my thesis, for his assistance and suggestions and for facilitating the honours thesis seminar, which provided me with a great deal of support. Special thanks also goes to the other honours students, who have been a strong support system to me throughout the year.

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 4

Abstract

Extraversion is a widely studied personality trait consisting of two separate constructs; agentic extraversion (AG) and affiliative extraversion (AF). AG reflects assertiveness, social dominance, and goal oriented behaviour. AF reflects warmth, affection, and the value of interpersonal bonds.

The validity of a new questionnaire measuring AG and AF was evaluated. Results of the new questionnaire were compared to the EPQ-R and the BIS/BAS Scale. In addition, AG and AF were compared to leisure activities and drug use to determine if the questionnaire could be used to predict leisure and drug use. Both AG and AF correlated with extraversion, and with different aspects of the BAS. It was expected that AG and AF would relate to different leisurely pursuits; however, leisure activities with correlations to each construct were similar. Finally, it was expected that due to the different underlying systems AG would correlate with use of stimulants, and AF with opiates; however, alcohol was the only significant correlation. While the questionnaire demonstrates some construct validity, more refinement of the measure is necessary to strengthen other aspects of construct validity.

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 5

Agentic & Affiliative Extraversion: A Psychometric Study

Extraversion

It is possible to understand human behaviour through the study of personality. Behaviour can be studied by examining differences in personality and character. By comprehending and appreciating differences in personality it is feasible to predict how one may react to their environment, others, or how they may perform in certain situations. Personality research is a way of characterizing and understanding each unique human being (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985). In personality research, extraversion is one of the most widely studied traits. It is consistently characterized as one of the major personality traits and is included in essentially all classifications of personality, sometimes with a different title (Depue & Collins, 1999; Eysenck

& Eysenck, 1985). Extraversion has been described as a trait reflecting sociability, vivaciousness, assertiveness, impulsiveness, activeness, and expressiveness (Costa & McCrae,

1995; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985). Furthermore, extraverted individuals are social and value interpersonal behaviour, and social dominance. Positive emotions including achievement and positive affect are also central aspects of extraversion (Depue& Collins, 1999).

Extraversion not only reflects sociability but liveliness, being carefree, responsive, and being outgoing. Venturesomeness and creativity have also been found to be related to extraversion. Individuals with higher levels of extraversion tend to be more talkative, highspirited, cheerful, and have more powerful needs for affiliation. These individuals also may think more positively and value excitement (Costa & McCrae, 1995; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985).

Extraverts seek social situations, value contact with others and leadership. Conversely introverts tend to avoid social situations; they are much more aroused by these situations. According to

Eysenck and Eysenck (1985), levels of cortical arousal differ between extraverts and introverts.

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 6

Eysenck suggested that extraverts often find themselves in situations when cortical arousal levels are too low. When faced with less stimulating situations extraverts will rely on external stimulation to raise their levels; this is often accomplished by contact with others. Those who are introverted typically have consistently higher levels of cortical arousal, leading to avoidance of interpersonal contact. According to this theory extraverts seek out the company of others and value interpersonal interactions due to their low levels of arousal.

In addition to seeking the company of others, extraverts tend to seek leisure activities that induce stimulation and excitement, and facilitate social interaction (Kirkcaldy &Furnham, 1991).

Activities that extraverts choose may include parties, dances, and competitive activities.

Extraverts are also inclined to participate in sports and become members of sporting clubs (Lu &

Hu, 2005). It has been found that extraversion also predicts involvement in competitive sports and sports performance (Kirkcaldy & Furnham, 1991). It has been suggested that for younger individuals, the best way to receive social contact is through team sports (Lu & Hu, 2005).

Extraverts choose leisure activities of a social nature whereas introverts choose solitary activities such as reading and watching television (Argyle & Lu, 1992). In addition to involvement in sports and social activities, extraversion is related to watching television soap operas (Lu & Hu,

2005). The greater involvement of extraverts in a variety of activities lends support to Eysenck and Eysenck’s (1985) hypothesis of lower cortical activity in extraverts (Eysenck, 1957).

Extraverts seek out activities that will increase their cortical arousal, offering explanation as to why extraverts choose to participate in group activities and introverts partake in solitary activities. Extraverts choose activities offering the most excitement, both physical and social (Lu

& Hu, 2005). Engaging in leisure activities also promotes feelings of pleasure and achievement

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 7 which are central aspects of extraversion (Hills & Argyle, 1998; Kirkcaldy & Furnham, 1991; Lu

& Hu, 2005).

Agentic and Affiliative Extraversion

In addition to feelings of pleasure and achievement, positive affect is also one of the defining characteristics of extraversion. Extraversion is comprised of traits that are measures of both behavioural and emotional characteristics that include social dominance, sociability, and achievement (Depue, 2006; Depue & Collins, 1999). There are several traits contributing to interpersonal behaviour, thus extraversion is not considered to be a unitary construct but a trait composed of two separate constructs; agentic and affiliative extraversion. Church and Burke

(1994) found through factor analysis of the NEO Personality Inventory that the traits measuring extraversion could be separated as two separate constructs. The traits were factored into two separate categories, now referred to as agency and affiliation. Agentic extraversion (AG) and affiliative extraversion (AF) are separate constructs that are reflective of the different facets of extraversion. Traits of assertiveness, excitement seeking, and achievement all are traits that load strongly with AG while warmth, positive emotions, and agreeableness all relate to AF. This study also includes a factor analysis of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire and this positive emotionality was also split into agentic and affiliative components. AG has high loadings from social potency and achievement and AF has loadings from social closeness. AG reflects social dominance and the enjoyment of leadership and AF reflects warmth and the value of interpersonal relationships.AG and AF reflect different aspects of personality and therefore surface as separate traits. For example, assertiveness and activity have been related to AG, and warmth and agreeableness likewise can be related only to AF (Church & Burke, 1994; Depue &

Collins, 1999; Depue, 2006; Digman, 1997).

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 8

Traits such as agreeableness, warmth, and affection are represented in AF and the value of interpersonal bonds is a central aspect of the trait. AG reflects social dominance, enjoyment of leadership, assertiveness, and being goal oriented. These traits are consistent with the two major traits that have been determined as warm-agreeable and assured-dominant in Wiggin's (1991) theory of interpersonal behaviour. AG and AF together characterize interpersonal behaviour.

Achievement, persistence, and activity are also attributes of AG, which are not reflected in AF.

Conversely, agreeableness and sociability are associated with AG and not AF. Sociability is central to AF but is a separate concept; sociability is quantitative in nature, referring to the frequency of interpersonal activities and AF is related to the quality and maintenance of interpersonal ties rather than the frequency of interactions (Depue, 2006; Depue & Collins, 1999;

Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005; Morrone-Strupinsky & Depue, 2004; Wiggins, 1991).

AG and AF are independent constructs that include a mutual underlying trait. Both wellbeing and positive emotions are associated equally with AG and AF. The correlation between

AG and AF and positive affect is in fact stronger than the correlation between AG and AF, meaning that positive affect is more related to the constructs than they are to each other (Depue,

2006; Depue & Collins, 1999; Morrone-Strupinsky & Depue, 2004; Watson & Clark, 1997).

This finding is consistent with previous research which has shown that both AG and AF are associated with positive emotions but not with each other (Depue, 2006; Depue & Collins, 1999;

Morrone, Depue, Scherer, & White, 2000).

Morrone-Strupinsky and Depue (2004) used films containing agentic and affiliative material to induce traits in order to discover which traits are linked to each construct. It was found that positive feelings were induced and related to both AF and AG. Films affiliative in nature induced feelings of warmth, and did not induce feelings linked to AG. Films with agentic

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 9 material induced feelings of incentive motivation and achievement, which are central to AG.

Through use of films inclusive of affiliative and agentic material it was possible to identify which positive emotions are associated with AF and AG. The feelings of warmth and affection that correlated to AF had no relation to AG. The different films induced emotions in AG and AF as the material induced feelings that are activated by different underlying neurobehavioural systems (Morrone et al., 2000).

It is proposed that because AG and AF reflect different traits they must be influenced by different underlying systems. Social dominance, goals, and achievement being the central aspects, AG must reflect a system that facilitates these behaviours. The interpersonal nature of

AF therefore displays activation of a system that promotes the formation and preservation of interpersonal bonds (Depue, 2006; Depue & Collins, 1999; Digman, 1997; Morrone et al., 2000).

AG and AF exhibit distinct underlying states and these states motivate response patterns to stimuli that have different effects on behaviour and cognition. Extraversion is associated with positive affect and therefore reflects an underlying system that guides behaviours towards achieving positive affect. The underlying systems of AG and AF guide behaviours toward positive affect, but through different mechanisms and behaviours, meaning the activation of these behaviours is through separate systems (Depue & Collins, 1999).

AG and AF both demonstrate systems that involve directing behaviours toward positive affect and reward; the distinguishing factor is the nature of that reward (Depue & Collins,

1999).The system underlying AG motivates behaviour toward achievement related rewards. AG is based on a neurobiological system that assimilates incentive motivation. Individual differences in AG are proposed to be differences in the functioning of this neurobiological system. AG

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 10 reflects the action of a neurobehavioral approach that is based on incentive and reward motivation that is goal oriented (Depue & Collins, 1999).

Incentive motivation is associated with positive feelings including elation, self-efficacy, wanting, desire, craving and potency. These experiences load very strongly with traits of dominance, persistence, achievement, endurance, activity, efficacy, and energy, which are all concordant with AG (Depue, 2006; Depue & Collins, 1999; Watson & Tellegen, 1985). Feelings of efficacy, ambition and mastery are involved in the behaviour of AG which includes attainment of both social and work related goals. Goals that are agentic in nature are important particularly in achievement related contexts, and interpersonal as well (Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005).

Depue and Collins (1999) refer to the underlying system that facilitates incentive motivation as the behavioural approach based on incentive motivation. AG is manifested in interpersonal contexts as well but goal direction and achievement are the underlying motivational factors. AG and AF are active in separate neurobiological and motivational systems therefore it is proposed that the distinguishing factor between AG and AF is the activational, or motivational component

(Carter, Lederhendler, & Kirkpatrick, 1997; Depue, 2006; Depue& Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005;

Morrone et al., 2000; Morrone-Strupinsky & Depue, 2004).

AG represents activity of a behavioural approach system that is based on positive incentive motivation (Depue, 2006; Depue & Collins, 1999). Previous research in animals demonstrates that positive incentive motivation and the experience of reward relies on a behavioural system that relies on the ventral tegmental area (VTA) as a part of the mesolimbic dopamine (DA) system in the midbrain. Projections from the VTA and DA system go to the nucleus accumbens (NAS) which is the integration site of information regarding incentive motivation. In this system DA is the key to the attainment of reward; DA plays an important role

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 11 in the facilitation of goal directed behaviour. This system facilitates the neural processes completing goal directed behaviour. DA receptor activation in the VTA and the NAS facilitate reward based on positive incentive motivation (Browman, Badiani, & Robinson, 1996; Depue &

Collins 1999; Mark, Blander & Hoebel, 1991; Mirenowicz & Schultz 1996; Mitchell & Gratton,

1992; Schultz, Apicella & Ljungberg, 1993).

DA cells, the majority of which can be found in the VTA, respond to the magnitude of incentive stimuli. These cells also respond actively and rapidly to the anticipation of reward

(Browman, et al., 1996; Depue & Collins 1999; Mark, et al., 1991; Mirenowicz & Schultz 1996;

Mitchell & Gratton, 1992; Schultz, et al., 1993). Individual differences in DA functioning is a factor in the variations of incentive-motivated behaviour, and thus AG (Depue, 2006; Depue&

Collins, 1999). Mice with differences in the number of neurons in the VTA and DA pathways demonstrated variations in behaviours dependent on DA release including self-administration of psychostimulants (Depue, 2006; Depue & Collins, 1999). Differences in this underlying DA system activating incentive motivation is what accounts for differences in AG (Depue & Collins,

1999).

The neurobehavioral process underlying AF involves creating a warm, affectionate state that is created by contact with others, which in turn motivates close interpersonal behaviour.AF represents neurobehavioral processes that create an affectionate subjective emotional state that is induced by others. This positive emotional state created by contact with others motivates further close interpersonal behaviours (Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005). It is this type of reward that has been hypothesized to be an underlying factor in all social relationships that contain a positive emotional element (Crews, 1998; Depue, 2006; Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005; ;

Insel, 1997; Mason & Mendoza, 1998). Psychobiological processes that initiate and maintain

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 12 bonds over longer periods of time are what promote affiliative behaviour through reward (Depue,

2006; Gingrich, Liu, Cascio, Wang, & Insel, 2000). Reward associated with AF is positive affect from interpersonal contact, and endogenous opiates play a key role in the facilitation of this form of reward. The release of endogenous opiates is increased during lactation and nursing, sexual activity, maternal social interaction, brief social isolation, grooming and other tactile stimulation that is not sexual in nature (Depue, 2006; Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005; Keverne, 1996;

Silk, Alberts, & Altmann, 2003). Opiates, along with DA, function to assist reward and interact in the NAS, resulting in independent effects (Depue, 2006; Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005).

The interaction between DA, opiates, and reward involves two processes. First, when anticipating goal acquisition motivated by incentive cues, opiate activation in the VTA increases release of DA in the NAS, facilitating the experience of reward (Depue, 2006; Marinelli &

White, 2000). The effects that ensue reward are a decrease of VTA neural firing rate (Depue,

2006; Marinelli & White, 2000). Opiate self-administration is not directly associated with DA function, meaning AF operates via a separate system from AG (Depue, 2006).

Affiliative reward is most strongly associated with mu opiate receptors. The effects of opiates on AF are from fibres that emerge from the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus and terminate in areas of the brain where mu opiate receptors are found. The mu opiate receptors may promote rewarding effects related to affiliative behaviours (LaBuda, Sora, Uhl, & Fuchs, 2000;

Schlaepfer et al., 1998; Wiedenmayer & Barr, 2000). The effects of reward are modulated in the

VTA and NAS as both structures promote self-administration of mu opiate receptor agonists. Mu opiate receptors provide rewarding effects which is demonstrated by the fact that animals will act for opiate receptor agonists, morphine and heroin, and in humans self-administration is dose dependent (Depue, 2006; Di Chiara, 1995; Nelson & Panksepp, 1998; Olson, Olson, & Kastin,

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 13

1997). Reward associated with AF is necessary in motivating behaviour. Experiencing affiliative reward is an integral element in the acquisition and maintenance of affiliative, or interpersonal, ties. It has been hypothesized that affiliative reward underlies human relationships in which positive affect is experienced (Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005).

Affiliative reward involves cues, such as smiles or sexual gestures, which act as incentive stimuli that will initiate firing of DA. This facilitates motivation such as desire, and the inclination to approach affiliative objects or stimuli. Once the stimulus is reached more proximal stimuli, such as tactile stimulation, activate feelings of reward including warmth and affection

(Depue, 2006; Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005). AF relies on an inherent capacity to experience reward facilitated by affiliative stimuli that is reflected in the emotional state that is assessed in measures of AF (Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005).

Extraversion and Drug Use

Based on the theory that extraverts are chronically under aroused, Eysenck (1957) hypothesized that extraverts will seek stimulation from external sources, such as certain drugs,

Eysenck (1957) proposed that drugs, particularly stimulants, that act on the central nervous system increasing excitation are drugs that extraverts may use. Stimulants, which include amphetamines, caffeine, and cocaine, decrease cortical inhibition leading to increased excitation, thus extraverts are more likely to engage in use of these substances. As extraverts rely on external sources to raise their low levels of cortical arousal to a more optimal level they may be inclined to use stimulants to do so. Research on drug preference shows that stimulants are among extraverts' preferred substances. Cocaine and amphetamines, particularly MDMA, are drugs that extraverts are more likely to use (Feldman, Kumar, Angelini, Pekala, & Porter, 2007;

Spotts & Shontz, 1984). Spotts and Shontz (1984) found that individuals using amphetamines

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 14 were among those scoring highest in extraversion. In addition to stimulants, those high in extraversion also engaged in the use of opiates. Eysenck's (1957) theory postulates that depressants are more likely to be used by introverts; however, AF is a construct activated by opiates. AG relies on the function of DA and AF relies on opiate functioning, therefore there should be different drug use patterns related to AG and AF (Depue& Collins, 1999; Depue,

2006).

Endogenous opiates are essential in order to maintain affiliative behaviour. In a study to find the relationship between opiates and interactions, females administered opiate antagonists had a decrease in social interaction and positive affect from interaction decreased (Depue &

Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005). Administration of morphine induces feelings of interpersonal warmth, well-being, euphoria, and elation (LaBuda, Sora, Uhl, & Fuchs, 2000; Schlaepfer, et al.,

1998; Wiedenmayer & Barr, 2000).When opiate antagonists are administered, selfadministration of opiates changes, that is, there is an increase, providing evidence that AF is related to the self- administration of opiates (Schlaepfer, et al., 1998).

AG is related to the use of substances that affect the DA pathway in the brain. Stimulants affect the central nervous system resulting in an activation of DA. Positive and motivational feelings central to AG such as euphoria, self-efficacy, desire, and craving are induced by DA receptors. In individuals addicted to stimulants, particularly cocaine, feelings associated with AG were activated through administration (Breiter, Aharon, Kahneman, Dale, & Shizgal, 2001;

Depue, 2006; Depue& Collins, 1999; Schlaepfer et al., 1998). Incentive motivation corresponds with positive emotions and motivational feelings, such as desire and self-efficacy, and these feelings can be generated through the use of stimulants. AG relies on the activation of DA for

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 15 incentive motivation, which as research demonstrates can be achieved through the use of stimulants (Drevets et al., 2001).

The Behavioural Activation System

Another construct reliant on DA is the Behavioural Activation System (BAS) (Corr,

2008; Gray, 1976). Gray (1976; 1982; 1987, as cited in Corr, 2008) postulated that the BAS is a part of the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory and is activated by an underlying system of reward.

The BAS is an construct included in the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (RST) of personality.

The BAS is a system underlying personality that is sensitive to reward and is activated by the presence of stimuli associated with reward and the absence of punishment. The BAS has been closely related to extraversion because extraversion reflects incentive motivation, and consists of positive affect and action-readiness Extraverts are more sensitive to signals of reward, as are individuals with a more active BAS (Corr, 2008; Depue& Collins, 1999; Gray, 1970, as cited in

Corr, 2008). The BAS and AG have both been explained in terms of functioning and variability of an underlying reward system. The BAS and AG are both related to a neurobehavioral approach sensitive to incentive and reward. The BAS is associated with reward hence DA is active and plays a key role in directing behaviour towards reward, not unlike AG (Corr, 2008;

Depue& Collins, 1999; Gray, 1976; 1982, as cited in Corr, 2008).

Psychometrics of AG and AF

AG and AF were identified as separate traits when Church (1994), and Church and Burke

(1994) completed a factor analysis of the NEO-PI, and MPQ Positive Emotionality, measuring extraversion. It became apparent that the different traits encompassing extraversion could be divided. It is assumed that agentic and affiliative behaviours and traits are in fact independent of

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 16 each other. At present there are no comprehensive measures of these traits, therefore there is a need for one (Depue, 2006; Gringrich, et al., 2000).

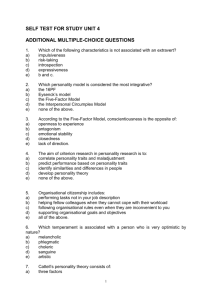

The purpose of the present study is to assess the validity of a new questionnaire measuring AG and AF. The construct validity of the questionnaire will be assessed by comparing the new measure to Eysenck’s Personality Questionnaire Revised (EPQ-R), and Carver and

White’s BIS/BAS Questionnaire. It is anticipated that AG will positively correlate with BAS, particularly the Drive component, as both constructs rely on similar underlying systems of reward (Corr, 2008; Depue& Collins, 1999). As AG and AF together comprise the construct extraversion, both are expected to positively correlate with extraversion (Depue & Collins,

1999).

In addition, leisure activities were measured. Based on research regarding extraversion and leisure activity preferences it is hypothesized that individuals scoring higher in extraversion will be likely to engage in activities that are social in nature (Hills & Argyle, 1998; Kirkcaldy

&Furnham, 1991; Lu & Hu, 2005). It will be possible to examine whether AG and AF are related to different leisure activities. Due to the fact that AG reflects an orientation towards achievement, AG will be related to leisure activities that facilitate achievement such as volunteering, and team sports, whereas AF will be related to leisure activities involving a greater deal of interpersonal interaction such as community activities and team sports (Depue & Collins,

1999; Depue, 2006; Depue & Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005).

Finally drug use was also measured. Based on Eysenck's (1957) theory of personality and drug use, extraversion is expected to be related to the use of drugs activating the CNS, specifically stimulants, as use increases release of DA. AG being a construct activated by DA, it is anticipated to be related to the use of cocaine, amphetamines, and cigarettes (Breiter, et al.,

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 17

2001; Depue & Collins, 1999; Drevets et al., 2001; Eysenck, 1957; Schlaepfer et al., 1998) . As opiates are what facilitate AF it is hypothesized that AF will be related to the use of opiates., particularly heroin and painkillers (Depue, 2006; Depue & Collins, 1999; Depue & Morrone-

Strupinsky, 2005).

Method

Participants

The participants of the current study were undergraduate psychology students. A total of

174 individuals participated aged 17 to 33 ( M =19.08, SD =2.21); 147 female, 23 male, and four who did not specify gender. Compensation was provided in the form of course credit.

Materials

Participants completed a total of five questionnaires: a new questionnaire measuring

AG/AF, BIS/BAS (Carver & White, 1994), EPQ-R (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1991), leisure, and a drug use questionnaire. The AG and AF questionnaire was formulated from scales taken from the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) (Goldberg et al., 2006) which include gregariousness, assertiveness, and warmth. Scales of excitement seeking, gregariousness, cheerfulness, and assertiveness from the IPIP NEO-PI were also added. Other IPIP scales similar to the California Psychological Inventory scales of forcefulness, and dominance have also been included. Finally, three scales were used from the IPIP Multidimensional Personality

Questionnaire Construct which are power seeking, achievement seeking, and joyfulness. The questionnaire contains 102 items with a five point rating scale ranging from very inaccurate to very accurate. The items are descriptive statements such as “ I wait for others to lead the way

”, “

I prefer to be alone ”, and “ I enjoy being a part of a group ” (See Appendix A).

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 18

The EPQ-R (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1991; test-retest reliability of .77, .83, .76 among males for P, E, and N, respectively, and .81, .89, .81 among females) is a 106 item questionnaire that measures extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism. The items are questions with yes and no response options. Items in the questionnaire include questions such as “ does your mood often go up and down?

”, “ do you like mixing with people?

”, and “ do you sometime like teasing animals?” .

Carver and White’s Behavioural Inhibition System and Behavioural Activation System

Scale (Carver & White, 1994; test-retest correlations .66 for BIS, .66 for Drive, .59 for Reward

Responsiveness, and -69 for Fun Seeking). This questionnaire measures the BIS/BAS as being two opposite ends of the personality spectrum. There are a total of 24 items including four response options. Each item is a statement that can be answered as being " very true for me " to

" very false for me " and items include “ I crave new excitement and sensations ”, and “ I worry about making mistakes

”.

Leisure activities among participants was also measured. This questionnaire measures the frequency of engagement in a list of 13 activities. There is a total of five response options ranging from never to very regularly. There is a broad range of activities including solitary activities such as individual sports, and computer use, and group activities such as team sports, community activities, and social clubs. Leisure activities including education and leadership have also been included (See Appendix B).

Drug use will also be included in the study. Items included in the questionnaire measure frequency in the use of a number of substances in the last 12 months with or without a prescription. A 7 point scale from "never" to " 40 times or more " has been implemented to determine the drug usage. A total of 16 different substances have been included, along with

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 19 different names for the substances. This questionnaire includes a number of substances including: stimulants such as cocaine ( also known as coke, snow, blow, etc ), cocaine in the form of crack, cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and amphetamines, opiates including prescription strength painkillers and heroin( also known as H, or junk ), and alcohol (See Appendix C).

Along with the five questionnaires a consent and debriefing form was given to participants. The consent form explained what was expected of participants. The form explains that confidentiality is ensured and that should at any point a participant is too uncomfortable to continue with the study they may withdraw without penalization. The purpose of the study was outlined and contact information of the researchers and departmental chair was provided. In addition a debriefing form was provided describing the purpose and goals of the study.

Procedure

Participants enrolled in the study via St. Thomas University Psychology Information

System. Upon signing up participants were provided with a link to the online questionnaires.

Before completing the study participants completed a consent form explaining the purpose of the study. Participants were informed that it would be possible to withdraw from the study without penalization. After completion of the questionnaires, Pearson’s r correlations were used to determine the relationship between AG and AF with EPQ-R, BIS/BAS Scale and leisure activities and drug use.

Results

The relation of AG and AF were analyzed through 2-tailed bivariate Pearson's r correlations. Results from the AG/AF questionnaire were compared to extraversion, resulting in a significant relationship between extraversion and AG and AF at the p <.01 level (see Table 1).

Table 1

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 20

Correlations between extraversion and AG and AF (separated by gender).

Female Male

Extraversion

AG

.53**

AF

.68**

AG

.32

AF

.68**

Note: Female ( n =146), Male ( n =23). ** p <.01.

Extraversion, AG, and AF were also correlated to the BAS. Among females the relationships between extraversion, AG, and AF, and BAS were significant at the p <.01 level for the BAS Reward Responsiveness, Fun Seeking, and BAS Drive. Furthermore the correlation between AG and BAS Drive was found to be significant. Findings were similar among males with the exception of AG, AF, and Fun Seeking, and extraversion and AF with Drive, at the p

<.05 level (see Table 2).

Table 2

Correlations between Extraversion, AG and AF and BAS components: Reward Responsiveness,

Fun Seeking, and Drive, separated by gender.

BAS Female Male

Extraversion AG AF Extraversion AG AF

Reward 0.42** 0.41** 0.42** 0.61** 0.44* 0.45*

Responsiveness

Fun Seeking

Drive

0.58**

0.32**

0.33**

0.51**

0.45**

0.22**

0.47*

0.33

0.41

0.47*

0.40

0.26

Note: Female ( n =146), Male ( n =23).BAS= Behavioural Activation System.** p <.01, * p <.05.

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 21

The relations among extraversion and leisure activities were significant at the p <.01 level for the following activities: team sports, individual sports, community activities and social clubs for females, and community activities for males. Similar correlations were found for AG and AF among females, with community activities being the only significant finding among males. Only leisure activities specifically related to the hypotheses have been reported (see Table 3).

Table 3

Summary of correlations between Extraversion, AG, and AF, and Leisure activities: Team sports, Individual sports, Computer Use, Community activities, Social clubs and Volunteer work

(separated be gender).

Leisure

Activities

Female Male

Extraversion AG AF Extraversion AG AF

Team Sports .31**

.23*

.20*

.20*

.20*

.31**

.28

.11

.19

.20

.36

.34 Individual

Sports/Exercise

Computer Use

Community

Activities

Social Clubs

Volunteer

Work

-.08

.16*

.33**

-.25*

.23*

.40**

-.05

.21*

.44**

-.06

.50*

.39

-.17

.41*

.26

.15 .37** .27** .28 -.03 .08

Note: Female ( n =146), Male ( n =23).** p <.01, * p <.05.

Significant correlations were found between alcohol and extraversion, and AF among both male and female participants at the p <.05 level (see Table 4).

Table 4

-.17

.30

.10

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 22

Summary of correlations between Extraversion, AG, and AF, and Substances Alcohol,

Stimulants, and Opiates within the last 12 months (separated by gender).

Female Male Substance (Use within last 12 months)

Extraversion AG AF Extraversion AG AF

Alcohol .44** .08 .25* .54* .36 .44*

Stimulants

Opiates

.20*

-.05

.00

.02

.01

-.05

.00

-.04

.35

-.17

.00

-.36

Note: Female ( n =146), Male ( n =23). Stimulants include cocaine, cocaine in the form of crack, methamphetamine and crystal methamphetamine, cigarettes, and smokeless tobacco. Opiates include heroin, and prescription strength pain killers. ** p <.01, * p <.05.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to assess the construct validity of a new questionnaire measuring AG and AF. Research suggests that AG and AF are separate constructs as they not only reflect different facets of extraversion, but are also manifestations of separate underlying systems, therefore is was predicted that AG and AF would be related to equally to extraversion, but would there would be no correlation between the two; however, a correlation was found.

Moreover, extraversion was found to relate to both AG and AF (Depue& Collins, 1999; Depue,

2006; Digman, 1997).

The BAS was also measured to identify the relation to AG. It is evident that extraversion is related to the BAS, however; a goal of this study was to demonstrate that AG and BAS are related because both constructs reflect underlying systems of reward. The correlation between

BAS Drive and AG was particularly significant, as both constructs rely on the achievement of goals (Corr, 2008; Depue & Collins, 1999; Gray, 1982, as cited in Corr, 2008; Marinelli &

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 23

White, 2000). Different aspects of the BAS correlated to AG and AF. In males, extraversion and

BAS Reward Responsiveness, and Fun Seeking were strong correlations among males. AG correlated to all aspects of the BAS as expected: Reward Responsiveness, Fun Seeking, and

Drive with Drive and AG being the strongest correlations. Among female participants all BAS constructs were significantly correlated with extraversion, AG, and AF. These findings support previous work that states extraversion and the BAS are similar (Corr, 2008; Gray, 1970; 1982).

An aim of the current research was to demonstrate that as AG and BAS are related, as both rely on a reward system. AG and BAS were related, but significant correlations were found for AF and BAS also. AF correlated least strongly with Drive, but equally with Reward Responsiveness, and Fun Seeking. It is hypothesized that AF relies on a type of affiliative reward; however, the significant correlations were not expected (Depue & Collins, 1999; Depue, 2006).

The relationship between extraversion and leisure activities is clear; extraverts engage in social activities such as team sports, parties, and going to clubs, bars, and social events

(Kirkcaldy & Furnham, 1991; Lu & Hu, 2005). It was anticipated that leisure activities would correlate differently to AG and AF. Due to the achievement related aspect of AG, activities expected to correlate to AG were team sports, and volunteer work, while activities expected to be related to AF were team sports, and community activities, as both provide interpersonal contact.

Among female participants, team sports, individual sports, community activities, and social clubs all yielded strong correlations to extraversion, AF, and AG. Volunteer work was correlated to both AG and AF, and computer use was negatively correlated to AG. Among males, community activities was the only activity to result in any correlation; a correlation to extraversion, and AG.

There are a number of possible factors influencing these unexpected findings on leisure.

Firstly the sample was primarily female. Second, females may be more inclined to participate in

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 24 a wide variety of activities, whereas males may not be. Individual sports was not expected to correlate to extraversion, AG, or AF; however, the female participants may prefer to participate in solitary exercise as it is not competitive or embarrassing.

Finally, it was expected that there would be differences in drug use between AG and AF.

AG is a system reliant on DA, and DA is increased by way of stimulants; therefore, use of stimulants such as amphetamines, cigarettes, and cocaine, were expected to relate to AG

(Drevets, et al., 2001). Regarding AF research indicates that affiliative behaviour is increased by the administration of opiates (Depue, 2006; Schlaepfer, et al., 1998). It was hypothesized that AF would correlate to the use of opiates such as heroin and painkillers. Based on the theory postulated by Eysenck (1957), extraverts prefer to use stimulants. There is support for this theory as findings suggest extraverts have a preference for amphetamines and cocaine; however, it has also been found that alcohol is among the most preferred substances in extraverts as well as introverts (Feldman et al., 2007; Spotts & Shontz, 1984). The present study found a correlation between extraversion and stimulants, supported by the female sample, conversely, there was no relationship among males. The substance most strongly correlated to extraversion however, was alcohol. There were also strong correlations between AG and AF, and alcohol. A negative

, albeit insignificant relation was observed between AF and opiates among both male and female participants.

One possibility for the relationship between extraversion and alcohol is that social individuals are more likely to be in situations in which alcohol is used. Extraverts typically prefer to attend social events and parties (Kirkcaldy & Furnham, 1991; Lu & Hu, 2005), and alcohol may often be served or promoted at these sorts of events. The demographics of the sample may also be a factor in the use of alcohol. The sample was university students and therefore may be

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 25 more apt to drink alcohol (Merline, O'Malley, Schulenberg, Bachman, & Johnston, 2004).

Research suggests that alcohol may be widely used in the younger population, and can be considered to increase likelihood of later use of substances such as opiates (Fiellin, Tetrault,

Becker, Fiellin, & Hoff, 2013). The age and type of the sample could also have been a factor in the insignificant findings of opiate and stimulant use. A sample of this age may not have been exposed to these substances, or may not be aware of substances they have used, and alcohol is an easier substance to obtain (Johnston, O' Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011). Furthermore, there could be an effect of under-reporting among participants, as many substances included in the questionnaire are illegal.

The questionnaire formulated to measure AG and AF showed differences between female and male participants. The sample from the current study was primarily female. Future research should aim to use a larger, and more diverse sample. The sample used for this study was undergraduate psychology students ages 17 to 33. This sample may not have allowed for accurate relationships between drug use and personality. This population may not have experience with the substances being assessed, and individuals who typically use different substances may not be likely to attend university. Concerning alcohol use, it may be beneficial in the future to add a measure of how and in what context the substances are used. Alcohol was strongly correlated to extraversion, AG, and AF, possibly because of sociability, but it is unknown whether or not alcohol was used by participants in a social setting. It would be interesting to add this measure to determine how substances are used. In the future a sample of more diverse individuals may also be necessary.

The disproportion of males and females may also be a factor in the major difference in the reports of leisurely activities. The sample included few males, which may be an explanation

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 26 as to why there was only a correlation between AG and one activity and the male sample should be increased for further study. Secondly, the sample may have included females who are interested in a number of activities. Thirdly, there may not have been enough of a difference between activities measured; for instance, volunteer work and community activities both correlated strongly to AG and AF, but some may consider them to be similar. The questionnaire asked the participants to indicate how often they participate in the activities. Many of the participants, particularly the males, may strongly enjoy team sports, but do not have the opportunity to participate. The same may be said for other activities as well. The differences between AG and AF and leisure activities found in this study may be more related to differences in gender, rather than AG and AF.

The purpose of this study was to examine the construct validity of the AG/AF questionnaire, and determine if the measure of AG and AF could predict other things such as leisure and drug use, in other words the predictive validity was assessed. If the questionnaire accurately measured AG and AF and had strong predictive validity, it would be possible to anticipate how participants would score on leisure and drug use measures. This questionnaire demonstrates some predictive validity in that it was possible to predict some leisure activities.

The activities hypothesized to be related to each construct were in fact correlated; however, the correlations were very similar between AG and AF.

Theoretically, the questionnaire would have measured AG and AF as separate constructs, and there would be no correlation between the two. There was a correlation between AG and AF, although not a particularly strong correlation, therefore if the measure is to be used in future research some alterations to the questionnaire should be made. It would be beneficial to complete a factor analysis of the questionnaire to determine which scales relate to AG and AF. There may

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 27 not have been enough discrepancies between the questions to measure AG and AF as separate constructs.

This questionnaire displays some convergent validity as AG and BAS were anticipated to be related. Extraversion, and AG are similar to BAS, and there were strong correlations providing convergent validity; however, AF and BAS were not expected to converge. Similarly,

AG and AF were expected to correlate to extraversion as together both comprise the trait. Both constructs did in fact converge with extraversion, providing evidence of convergent validity.

For further study of the constructs AG and AF the measure in question may need to be modified. It is feasible that some of the questions intended to measure AG may have related to

AF. Many of the scales included in the questionnaire are content that clearly measure either construct; however, some may not be distinct enough. Some items such as " express childlike joy", "am the last to laugh at a joke", and am willing to try anything once", may be items that do not provide a clear separate measure of AG and AF, but with modification to the questionnaire this can be remedied.

This questionnaire is beneficial as it can be used to assess AG and AF, and demonstrates validity. It was expected that AG and AF would relate to extraversion, and this was supported.

The expectation was that AG, and extraversion, would correlate to the BAS, and this was also supported; however, AF also correlated to all aspects of the BAS. AG and AF were expected to correlate to distinct leisure activities, team sports and volunteer work versus social clubs, community activities, and team sports, and this was partially supported. Finally stimulants were expected to correlate to AG, and opiates to AF. While extraversion was correlated to stimulants,

AG was not, and a negative relationship between AF and opiates was observed. Alcohol was the substance most significantly correlated to each construct. The AG/AF questionnaire may be used

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 28 in the future to predict leisure and drug use after further refinement of the questions, and by using a different sample. This questionnaire has its merits as it demonstrates that AG and AF can be evaluated as distinct personality constructs. Aspects of construct validity have been assessed, and the questionnaire does in fact provide construct validity. AG and AF were found to relate differently to other personality constructs, and there were differences in drug use and leisure involvement between the constructs. The objective of this research was to demonstrate the value in measuring AG and AF as separate constructs, rather than simply measuring extraversion.

Through using the questionnaire it is clear that AG and AF are separate constructs, and should be measured as such. The current findings encourage future research, as this questionnaire may be the beginning of a new way to measure extraversion

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 29

References

Argyle, M. and L. Lu (1992). 'New directions in the psychology of leisure’, TheNew

Psychologist 1, pp. 3–11.

Breiter, H. C., Gollub, R. L., Weisskoff, R. M., Kennedy, D. N., Makris, N., Berke, J. D. et al

(1997). Acute effects of cocaine on human brain activity and emotion. Neuron, 19, 591-

611.

Browman, K, Badiani, A. & Robinson, T. (1996). Fimbria-fornix lesions do not block sensitization to the psychomotor activating effects of amphetamine. Pharmacology,

Biochemistry and Behaviour 53 (4), 899-902.

Carter CS, Lederhendler I, & Kirkpatrick B. (1997). The integrative neurobiology of affiliation. introduction.

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 807

Carver, Charles S.; Terry L. White (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology 67 (2): 319–332

Church, A. T. (1994). Relating the tellegen and five-factor models of personality structure.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67 (5), 898-909. doi: 10.1037/0022-

3514.67.5.898

Church, A. T., & Burke, P. J. (1994). Exploratory and confirmatory tests of the big five and tellegen's three- and four-dimensional models. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 66 (1), 93-114. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.66.1.93

Corr, P. (2008). The reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality. New York, NY. Cambridge

University Press

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 30

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1995). Primary traits of Eysenck's P-E-N system: Three- and five-factor solutions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69 (2), 308-317. doi:

10.1037/0022-3514.69.2.308

Depue, R. A. (2006). Interpersonal behaviour and the structure of personality: Neurobehavioral foundation of agentic extraversion and affiliation. In T. Canli (Ed.), (pp. 60-92). New

York, NY US: Guilford Press

Depue, R. A., & Collins, P. F. (1999). Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences,

22 (3), 491-569. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X99002046

Depue, R. A., &Morrone-Strupinsky, J. (2005). A neurobehavioral model of affiliative bonding:

Implications for conceptualizing a human trait of affiliation. Behavioral and Brain

Sciences, 28 (3), 313-395. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000063

Di Chiara, G. (1995). The role of dopamine in drug abuse viewed from the perspective of its role in motivation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 38 (2), 95-137. doi: 10.1016/0376-

8716(95)01118-I

Digman, J. M. (1997). Higher-order factors of the big five. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 73 (6), 1246-1256. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1246

Eysenck, H, J, (1957). Drugs and personality: I. Theory and methodology. Journal of Mental

Science, 103 , 119-131.

Eysenck & Eysenck (1985). Personality and individual differences . New York, N.Y: Plenum

Press.

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 31

Feldman, M., Kumar, V. K., Angelini, F., Pekala, R. J., & Porter, J. (2007). Individual differences in substance preference and substance use. Journal of Addictions & Offender

Counseling, 27 (2), 82-101

Fiellin, Lynn E.;Tetrault, Jeanette M.;Becker, William C.;Fiellin, David A, Hoff, Rani A.

Previous use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana and subsequent abuse of prescription opioids in young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health 52 (2):158

Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R., &

Gough, H. C. (2006). The International Personality Item Pool and the future of publicdomain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40 , 84-96.

Gray, J. A. (1970). The physchophysiological basis of extraversion-introversion, Behaviour

Research and Therapy , 8, 249-266.

Gray, J. A. (1976). The behvioural inhibition system: a possible substrate for anxiety in M. P

Feldman and A.M Broadhurst (eds), Theoretical and Experimental Bases of Behavioural

Modification (London: Wiley), pp. 246-276

Gray, J. A. (1982). The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the Functions of the septohippocampal system. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gray, J. A. (1987). Perspectives on anxiety and impulsivity: A commentary, Journal of Research in Personality, 21 , 493-509

Gingrich, B., Liu, Y., Cascio, C., Wang, Z., &Insel, T. R. (2000). Dopamine D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens are important for social attachment in female prairie voles

(microtusochrogaster).

Behavioral Neuroscience, 114 (1), 173-183. doi: 10.1037/0735-

7044.114.1.173

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 32

Hills, P. and M. Argyle: 1998, ‘Musical and religious experiences and their relationship to happiness’, Personality and Individual Differences 25 , pp. 91–102.

Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2010 Ann Arbor: Institute for

Social Research; Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, 2011

Keverne, E. B. (1996). Psychopharmacology of maternal behaviour. Journal of

Psychopharmacology 0269-881110(1):16 SAGE Publications

Kirkcaldy, B., &Furnham, A. (1991). Extraversion, neuroticism, psychoticism and recreational choice. Personality and Individual Differences, 12 (7), 737-745. doi: 10.1016/0191-

8869(91)90229-5

LaBuda, C. J., Sora, I., Uhl, G. R., & Fuchs, P. N. (2000). Stress-induced analgesia in μ-opioid receptor knockout mice reveals normal function of the δ-opioid receptor system.

Brain

Research, 869 (1-2), 1-5. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02196-X

Lu, L., & Hu, C. (2005). Personality, leisure experiences and happiness. Journal of Happiness

Studies, 6 (3), 325-342. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-8628-3

Marinelli, M., & White, F. (2000). Enhanced vulnerability to cocaine self-administration is associated with elevated impulse activity of midbrain dopamine neurons. Journal of

Neuroscience, 20, 71-84.

Mark, G., Blander, D. &Hoebel, B., (1991). A conditioned stimulus decreases extracellular dopamine content in the nucleus accumbens after the development of a learned taste aversion. Brain Research 5(11):308–23

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1995). Trait explanations in personality psychology.

European

Journal of Personality, 9 (4), 231-252. doi: 10.1002/per.2410090402

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 33

Mirenowicz, J. & Schultz, W., (1996). Preferential activation of midbrain dopamine neurons by appetitive rather than aversive stimuli. Nature 379:449–51

Merline, A.C., O’Malley, P.M., Schulenberg, J.E., Bachman, J.G., Johnston, L.D., (2004).

Substance use among adults 35 years of age: prevalence, adulthood predictors, and impact of adolescent substance use. Am. J. Public Health 94 , 96–102

Mitchell, J. &Gratton, A. (1992). Partial dopamine depletion of the prefrontal cortex leads to enhanced mesolimbic dopamine release elicited by repeated exposure to naturally reinforcing stimuli . Journal of Neuroscience 12:3609–14

Morrone, J. V., Depue, R. A., Scherer, A. J., & White, T. L. (2000). Film-induced incentive motivation and positive activation in relation to agentic and affiliative components of extraversion. Personality and Individual Differences, 29 (2), 199-216. doi:

10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00187-7

Morrone-Strupinsky, J., &Depue, R. A. (2004). Differential relation of two distinct, film-induced positive emotional states to affiliative and agentic extraversion. Personality & Individual

Differences, 36 (5), 1109. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00204-6

Nelson, E. E., & Panksepp, J. (1998). Brain substrates of infant–mother attachment:

Contributions of opioids, oxytocin, and norepinephrine. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral

Reviews, 22 (3), 437-452. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(97)00052-3

Olson, G. A., Olson, R. D., & Kastin, A. J. (1997). Endogenous opiates: 1996.

Peptides, 18 (10),

1651-1688. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(97)00264-7

Schlaepfer, T. E., Strain, E. C., Greenberg, B. D., Preston, K. I., Lancaster, E., Bigelow, G. E., et al., (1998). Site of opioid action in the human brain: Mu and kappa agonists’ subjective and cerebral blood flow effects. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155 (4), 470-473.

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 34

Schultz, W., Apicella, P. &Ljungberg, T. (1993) Responses of monkey dopamine neurons to reward and conditioned stimuli during successive steps of learning a delayed response task.

Journal of Neuroscience 13:900–18.

Silk, J. B., Alberts, S. C., & Altmann, J. (2003). Social bonds of female baboons enhance infant

Survival. Science, 302, 1231-1234.

Spotts, J. V., &Shontz, F. C. (1984). Drugs and personality: Extraversion-introversion.

Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40 (2), 624-628

Tellegen, A., Waller, N. G., Depue, R. A., Luciana, M., Arbisi, P., Collins, P., & Leon, A.

(1994).Multidimensional personality questionnaire.

Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 67 , 485-498

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1997).Extraversion and its positive emotional core. In R. Hogan, J.

A. Johnson & S. R. Briggs (Eds.), (pp. 767-793). San Diego, CA US: Academic Press. doi:

10.1016/B978-012134645-4/50030-5

Watson, D., & Tellegen, A. (1985).Toward a consensual structure of mood.

Psychological

Bulletin, 98 (2), 219-235. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.219

Wiedenmayer, C. P., & Barr, G. A. (2000).μ Opioid receptors in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray mediate stress-induced analgesia but not immobility in rat pups.

Behavioral

Neuroscience, 114 (1), 125-136. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.114.1.125

Wiggins, J. S. (1991). Agency and communion as conceptual coordinates for the understanding and measurement of interpersonal behavior .In W. M. Grove, & D. Cicchetti (Eds.), Thinking clearly about psychology: personality and psychopathology (pp. 89–113). Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press.

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 35

Appendix A

Agentic&Affiliative Extraversion Questionnaire indicate how accurate or inaccurate the item describes you. Please respond to all the items; do not leave any blank. Choose only one response to each statement. Please be as accurate and honest as you can be. Respond to each item as if it were the only item. That is, don't worry about being "consistent" in your responses. Choose from the following five response options:

Item

Very

Inaccurate

Moderately

Inaccurate

Neither

Accurate nor

Inaccurate

Moderately

Accurate

Very

Accurate

1 Enjoy bringing people together.

1 2 3 4 5

2 Make people feel at ease.

3 Let others make the decisions.

4 Radiate joy.

5 Do too little work.

6 Seldom joke around.

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

7 Readily overcome setbacks.

8 Lay down the law to others.

9 Try to surpass others' accomplishments.

10 Excel in what I do.

11 Don't like to get involved in other people's problems.

12 Avoid crowds.

13 Am not afraid of providing criticism.

14 Express childlike joy.

15 Enjoy being reckless.

16 Want to be left alone.

17 Am easily intimidated.

18 Try to outdo others.

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 36

19 Have a dark outlook on the future.

1 2 3 4 5

20 Hate to seem pushy.

21 Take control of things.

22 Would never go hang gliding or bungee jumping.

23 Enjoy being part of a group.

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

24 Don't like to draw attention to myself.

25 Often feel blue.

26 Demand explanations from others.

27 Lack the talent for influencing people.

28 Am very pleased with myself.

29 Cheer people up.

30 Enjoy being part of a loud crowd.

31 Am willing to try anything once.

32 See myself as a good leader.

33 Say what I think.

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

34 Work too much.

35 Am apprehensive about new encounters.

36 Feel lucky most of the time.

37 Like to take it easy.

38 Give up easily.

39 Am the last to laugh at a joke.

40 Am not really interested in others.

41 Can take strong measures.

42 Am not highly motivated to succeed.

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 37

43 Find it difficult to manipulate others.

1 2 3 4 5

44 Laugh my way through life.

45 Have little to say.

46 Love large parties.

47 Am often in a bad mood.

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

48 Involve others in what I am doing.

49 Amuse my friends.

50 Try not to think about the needy.

51 Never challenge things.

52 Seek to influence others.

53 Hold back my opinions.

54 Challenge others' points of view.

55 Take charge.

56 Have a natural talent for influencing people.

57 Plunge into tasks with all my heart.

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

58 Have a low opinion of myself.

59 Continue until everything is perfect.

60 Put people under pressure.

61 Am easily discouraged.

62 Can talk others into doing things.

63 Seek danger.

64 Talk to a lot of different people at parties.

65 Do more than what's expected of me.

66 Love surprise parties.

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 38

67 Let myself be pushed around.

1 2 3 4 5

68 Am good at making impromptu speeches.

69 Am afraid that I will do the wrong thing.

70 Am not embarrassed easily.

71 Do just enough work to get by.

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

72 Take an interest in other people's lives.

73 Want to be in charge.

74 Impose my will on others.

75 Prefer to be alone.

76 Take time out for others.

77 Love action.

78 Work hard.

79 Try to lead others.

80 Love life.

81 Look at the bright side of life.

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

82 Know how to comfort others.

83 Feel others' emotions.

84 Laugh aloud.

85 Take the initiative.

86 Want to control the conversation.

87 Am quick to correct others.

88 Love excitement.

89 Joke around a lot.

90 Don't like crowded events.

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 39

91 Dislike loud music.

1 2 3 4 5

92 Am not easily amused.

93 Have a slow pace to my life.

94 Keep in the background.

95 Feel that my life lacks direction.

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

96 Seek quiet.

97 Just know that I will be a success.

98 Wait for others to lead the way.

99 Have a lot of fun.

100 Seek adventure.

101 Am the life of the party.

102 Act wild and crazy.

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 40

Appendix B

Question Item Never Rarely Sometimes Often

Very

Regularly

1

Team sports (i.e.; hockey, baseball, basketball, volleyball, soccer)

2

Individual sports/exercise (i.e; jogging, running, swimming, bike riding, tennis, walking, golf, badminton, weightlifting, yoga)

3

Music (i.e.; Singing, playing instrument, attending concerts, listening to music)

4

Arts and crafts (i.e.; painting, drawing, photography, woodworking, jewelry making)

5

Table games (i.e.; cards, checkers, chess, board games, puzzles, dominoes)

6

Outdoor activities (i.e.; hiking, climbing, gardening, camping, skiing, boating)

7

Community activities (i.e.; attending sports events, dining out, museums, concerts, shopping)

8

Social clubs (i.e.; cultural ethnic, card play, religious)

9

Literacy/continuing education (i.e.; reading, letter writing, adult education classes)

10

Volunteer work (i.e.; political campaign, homeless shelter, SPCA, nursing home)

11

Watch television (i.e.; News, sports, reality, comedy, drama)

12

Travel (i.e.; out of town, out of province, travel abroad)

13

Computer use (not work related) (i.e.; videogames, social media (Facebook; twitter; etc.), chat)

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 41

Appendix C

Drug Use Questionnaire

Instructions

Please report how often you have used each of the following in THE LAST 12 MONTHS :

Report use either by prescription or without prescription. Please be as honest and accurate as you can. Remember that your responses will be confidential and anonymity is ensured.

Item

1 Smoke Cigarettes

Never

1-2 times

3-5 times

6-9 times

10-19 times

20-39 times

0 1 2 3 4 5

40 or more times

6

2

Smokeless tobacco

(also known as chewing tobacco, snuff, plug, dipping tobacco)?

3

Alcohol – Liquor

(rum, whiskey, etc.), wine, beer, coolers?

4

Cannabis

(also known as marijuana, weed, pot, grass, hashish, hash, hash oil, etc.)

5 LSD or acid

6

Psilocybin or Mescaline

(also known as magic mushrooms, shrooms, mesc, etc.)

7

Cocaine

(also known as Coke, blow, snow, powder, snort, etc.)

8 Cocaine in The Form Of Crack

9

MDMA or Ecstasy

(also known as E, X)

10

Prescription strength Pain Killers

(such as Percocet, Tylenol #3, Demirol,

OxyContin, codein)

11

Methamphetamine or Crystal

Methamphetamine

(also known as speed, crystal meth, prank, ice, etc.)

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

AGENTIC AND AFFILIATIVE EXTRAVERSION 42

Item Never

1-2 times

3-5 times

6-9 times

10-19 times

20-39 times

40 or more times

12

Heroin

(also known as H, junk, smack, etc.)

13

Adrenochromes

(also known as wagon wheels)

14

Stimulants Such As Diet Pills and Stay

Awake Pills

(also known as offers, pennies, taxis, pep pills, etc.)

15

Sedatives or Tranquilizers

(such as Valium, Ativan, Xanax)

16

Medicine to Treat ADHD

(such as Ritalin, Concerta, Adderall,

Dexedrine)

0

0

0

0

0

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

6

6

6

6

6