self-interest - York University

advertisement

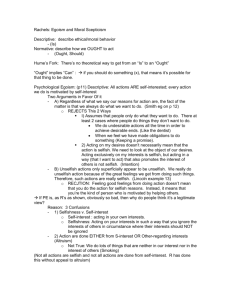

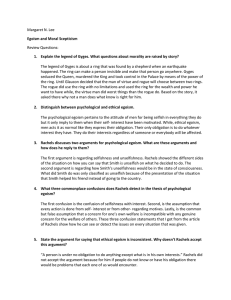

Psychological egoism / Ethical egoism Plato’s The Myth of Gyges (from The Republic), in the words of Glaucon, representing the views of Thrasymachus Q: whether it is better to be just or unjust? A: that depends upon what kind of value justice has. Values can be intrinsic, instrumental, or both (e.g., constitutive) To be intrinsically good, a thing or state of affairs must be good for its possessor, independently of its consequences. To be intrinsically good, a thing must be worth having for its own sake, because of its intrinsic properties. Intrinsic value is not dependent on “opinion”. (73) To be instrumentally valuable is to be valuable as a means to another end. Q: what value does justice have? A: Glaucon: only instrumental; justice is not good in itself, but good only because it is necessary as a means to things that are intrinsically good. Proof: if it was not necessary to other things we value, we would not value it at all. Shown by the Myth of Gyges and the thought experiment in which justice does not have its usual good consequences (is not a means to other good things) and injustice does not have its usual consequences (does not lead to states that are disvalued for themselves). “What people say is that to do wrong is, in itself, a desirable thing; on the other hand, it is not desirable to suffer wrong, and the harm to the sufferer outweighs the advantage to the doer. Consequently, when men have had a taste of both, those who have not the power to seize the advantage and escape the harm decide that they would be better off if they made a compact neither to do wrong not to suffer it.” (66) This is the origin of laws, justice, right. Best of all: to do wrong with impunity. Worst of all: to suffer wrong without the power to retaliate. 1 Justice is valuable only because we lack the power to do wrong with impunity. Principle of equality: each will refrain from doing harm in order to avoid suffering harm; each will accept a principle of mutual restraint: none of us will do harm to the others. A person with the power to do wrong with impunity would be ‘mad’ to enter into a compact with others to do no wrong. Whether a person be just or unjust, if given the power, he will pursue his self-interest without restraint: “he will be moved by self-interest, the end of which is natural to every creature to pursue as good, until forcibly turned aside by law and custom to respect the principle of equality.” (67) Thought Experiment One: Ring of Gyges Variation on Gyges: Imagine that a perfectly just person and a completely unjust person are both given the magic invisibility rings (invisibility cloaks in Harry Potter). Both will quickly act the same way, respecting no moral restraints on their actions. Thought Experiment Two: Switched Reputation Who is happiest at the end of his life? Lesson: It is better to see just than to be just. It is the appearance of justice, rather than the reality of justice, that is valuable. Thought Experiments Support Psychological Egoism PE: psychological egoism (PE). PE = Their own self-interest is the only thing that people desire or pursue for its own sake (as an intrinsic end). The only motive from which anyone ever acts is self-interest. A descriptive, empirical claim about what motivates people to act. Only as a Universal claim is it contentious; we must allow that sometimes everyone acts on their own self-interest (e.g., when the interests of no one else will be affected by what he does). 2 Contrasts with Altruism or Duty: at least some of the time, people act for the good of others (as an end), or for the sake of fulfilling a duty or because of an obligation they accept they have, when doing so is contrary to their selfinterest. Arguments for PE: 1. Ownership argument. Every intentional action is motivated by a desire of mine. So every intentional action must be motivated by a good I am trying to achieve for myself. Problems: Weak as an argument showing that all our desires are selfish, aimed at our own good, because we could desire the good of others. Logical fallacy: derives a factual proposition (egoism) from a conceptual claim (tautology) (my motives are my motives). Confuses the origin / source of the desire with its objective/ end/ content. The main weakness of these kinds of arguments is that they confuse selfishness with self-interest. 2. If we act for the good of others, we are really doing it because we get pleasure from our own good conduct. Our own pleasure is basic. Problems: Weak unless the only thing we take pleasure in is our own good. Confuses the results of desire satisfaction with the objective / end / content of the desire. It cannot explain why we get satisfaction from benevolent acts, because to suppose we get satisfaction from them supposes that we care about them independently of our desires for satisfaction. Only if we really care about others do we get satisfaction from helping them. Only an unselfish person, 3 or a person who cared about fulfilling her obligations, would suffer a bad conscience by acting egoistically, by letting others suffer when she could help, or by failing to do what she thinks she has a duty to do. Rachels makes this point this way: “if we have a positive attitude toward the attainment of some goal, then we may derive satisfaction from attaining that goal. But the object of our attitude is the attainment of that goal; and we must want to attain the goal before we can find satisfaction in it” and “if someone desires the welfare and happiness of another person, he will derive satisfaction from that; but this does not mean that this satisfaction is the object of his desire, or that he is only selfish on account of it.” (77) Makes a whole host of common-sense motives unintelligible: not just benevolent ones, but malevolent ones too. 3. Self-deception We know that we sometimes deceive ourselves about our own motives, supposing them to be altruistic or generous when they are really selfish. Perhaps we do this always. In fact, if you look deeply enough, we can always find a selfish motive to explain even the most generous and selfless behaviour: to win approval, because ethical behaviour is good business, for a good conscience, etc. Problems: Inconclusive: we might all be suffering from self-deception, but we would need empirical evidence that this is true before we should believe it. Makes PE a theory with no explanatory force. Makes PE an irrefutable theory – very bad for what is supposed to be an empirical, descriptive theory. Contrast empirical / factual claims with analytic or conceptual claims. 4. Moral Education 4 Moral education and moral motivation seem to require the use of rewards and punishments. This supports the view that we are ultimately led only by selfish desires, to achieve good for ourselves and to avoid what is painful. Problems: We cannot teach children just to desire their own happiness. We cannot teach children to be egoists, because taking happiness as our goal is usually self-defeating. Problems with Psychological Egoism: Disguised analytic claim, rather than empirical. The critiques of it usually depend upon conflating selfishness and selfinterest. But they also often rest on a series of false dichotomies. (1) Every act is either done from other-regarding motives or from self-regarding motives. But some acts serve neither self-interest nor other-interests, such as smoking. (But consider problems with this view, addiction, weakness of will.) (2) A concern with one’s own welfare is incompatible with a concern for others’ welfare. But often they are not in conflict, so one can satisfy both by the same act (e.g., study group, consensual sex). Or, one can desire that everyone, oneself and others, be well-off and happy. When our interests do conflict with those of others, then what? That is the real question. Rachels says that at least sometimes, when we have to choose between satisfying our own interests or acting to serve the interests of others, we choose to satisfy the interests of others rather than our own (e.g., in families). If so, then PE is false as a descriptive matter. If we think we cannot, or at least never do, choose to act contrary to our own interests in order to serve the good of others, then we accept that PE is true. Ethical Egoism (EE) Categorical (and universal) egoism: We all ought to observe our own interests. There is no further reason why we ought to act egoistically. 5 A normative, moral claim, about what we ought to do. Purports to be actionguiding. “[M]en … have no obligation to do anything except what is in their own interests… [A] person is always justified in doing whatever is in his own interests, regardless of the effect on other”. (75) Is this short-sighted? Will it lead to monstrous results? Again, we should distinguish selfish behaviour from self-interested behaviour. EE says we all ought to act in our own self-interest. If being selfish would not actually be in your interests (because it would thwart your ability to satisfy your desires or lead others to shun you) then you should not act selfishly. Enlightened Egoism is a form of EE: Rachels points out that EE leads to monstrous results only if we ignore the crucial fact that living peacefully and cooperatively with others in society is in our own self-interest. We should be moral, and act in accordance with rules that benefit others, because that is good for each of us, in the long run and under normal circumstances. This is just the view Glaucon promotes. I think this is the right view, and it leads to contractarianism. But Rachels says it won’t work, because we don’t need universal compliance in order to get the benefits of peace and cooperation. An egoist will want to an exception for himself; he will want everyone else to act morally and follow the mutually beneficial rules, while he is free to act as he pleases. It is in the egoist’s interests to encourage others to be moral, while he is free to directly maximize the satisfaction of his own desires (at least when he can do so secretly). The smartest egoist wants to be an egoist in a society of altruists. THIS IS NOT EE: We all ought to observe our own interests, because doing so will produce better results for everyone than any other principle of action. This is not really egoism but a disguised form of utilitarianism. Criticisms of EE: 6 Conflicts with our intuitions about justice, fairness, what moral dispute and inquiry and disagreement is about, our attitude toward the force of duty and obligations, what we ought to do because of various roles we occupy, such as friends or parents or siblings. Esoteric. To say that a person ought to do something is typically to say that we approve of his doing it and to attempt to get others to share our attitude. But can we approve of everyone else acting for their own good, when that interferes with our good? We are involved in a contradiction at the level of attitudes if we try to assert categorical egoism. And we don’t typically give our highest moral praise to those who are best at pursuing their own interests; quite the opposite. When we give moral advice, or are wondering what we should do, it does not seem like we are wondering what would be best for the advisee or ourselves, understood egoistically. Same goes for trying to justify our conduct to others. Ethical egoism cannot be universalized. Supposes that all claims about what is right or ought to be done have this form: if P ought to do X in circumstances C, then everyone ought to do X in C. Consistency in evaluations and recommendations for action is required. Rachels’ answer: the welfare of human beings matters intrinsically, or, “the welfare of human beings is something that most of us value for its own sake, and not merely for the sake of something else.” (81) No further reasons can be given in favour of policies than that they serve what is intrinsically valuable / what we value intrinsically. The argument ends here, because it is a fundamental requirement of rational action that the existence of reasons for action always depend on the prior existence of certain attitudes in the agent. That X will make P a lot of money gives P a reason to X only if P wants lots of money. That X will increase your chances of success in university only gives you a reason to do X if you want to succeed in university. This reflects the ‘internal reasons’ view of reasons for action. 7 It is because Rachels accepts the internal view of reasons that he said ‘we value’ human wellbeing, rather than that human wellbeing is valuable or a value. Self-interest only gives us a reason to act for our own good if we care about our own wellbeing (depression, self-loathing). The interests of others give us a reason to act for their good only if we care about their wellbeing (psychopaths, sociopaths). If ‘ought’ implies ‘can’, then psychological egoism implies ethical egoism (if PE says not only that we all do only seek our own self-interest, but also that self-interest is all we can seek; we can do no other than act in selfinterested ways). 8