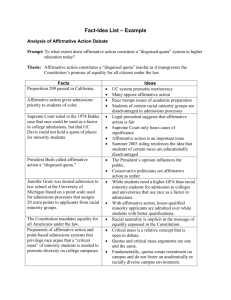

Appendix A: Affirmative Action and Student Experiences

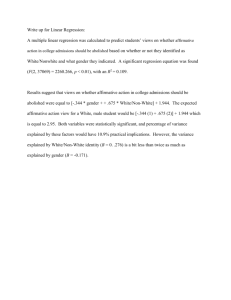

advertisement