Critical Care Plan #3

advertisement

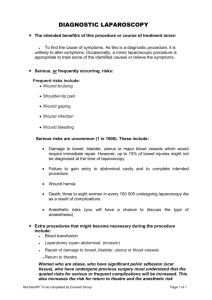

Admission date: 9/23/14 Admitting diagnosis: Small bowel obstruction Surgical procedure: Exploratory laparoscopy Exploratory laparotomy Lysis of adhesions Release of small bowel obstruction (9/28/14) Pertinent PMH/PSH Hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cervical cancer, anemia, arthritis, tobacco use Last V/S, including O2 sat and pain scale T-98.1, HR-70bpm, RR-16, 02sat-95%, BP-143/91 Pain-0 Current treatments (IV, medications, catheters, tubes, drains. O2, ostomies) 22 gauge R. forearm, Gastric Tube (NG) Recommended consults: Nutrition, Cardiology Nutrition-NPO PT/OT/Speech-N/A Mental Health-N/A Other-tobacco type: beer, drinks daily; tobacco type: cigarettes(0.5 packs/day), current smoker Risk factors Pathophysiology Adhesions Tumors of small intestine Crohn’s disease Cancer with the abdomen Hernias Decreased blood supply to small bowel “A small bowel obstruction is when intestinal contents, fluid, and gas accumulated above the intestinal obstruction” (Smeltzer et al., 2010, p.1097). Abdominal distention and retention of fluid decrease the absorption of fluids and stimulate more gastric secretion. Reflux vomiting is common due to the distention. Vomiting decreases electrolytes and leads to dehydration. Lab values with discussion of expected/unexpected findings Patient S/S Nausea (on admission and current) Vomiting (on admission and current) Abdominal pain (right upper quadrant & crampy) (on admission) Diagnostic tests with discussion of expected/unexpected findings Glucose (125) high; Normal: 60-100 Sodium (133)low; Normal-136-145) Creatinine(0.4) low; Normal-0.6-1.1 Red Blood Cells(5.68) high; Normal-4.2-5.4 Hematocrit(50) high; Normal-37-47% Calcium (11.5) high; Normal-9.0-10.5 Albumin(3.4) low; Normal-3.5-5 Protein total serum(6.1) low; Normal-6.08.3 BUN(6)low; Normal-10-20 XR-abdomen flat/upright w/Chest IVResults: dilated small bowel loops; nonspecific air fluid XR abdomen AP- Results: finding consistent with small bowel obstruction CT Angio Chest-Results: no PE, aortic aneurysm, or dissection; bullous emphysema-predominantly upper lobes, small bilateral effusions, bilateral lob atelectasis greater on left Priority Nursing Diagnoses- rank these Focus on top 2 1. Acute pain r/t surgical incision of abdomen AEB patient reporting 6/10 on pain scale after surgical procedure located in abdomen, mild abdominal tenderness, administration of 0.4 mg/ml, dilaudad, IV, PCA, PRN. 2. Dysfunctional gastrointestinal motility r/t surgery AEB hypoactive bowel sounds on assessment, placement of a Gastric Tube (NG tube), decrease of flatus, vomiting/nausea with clear liquids and absence of bowel movement. 3. Imbalanced Nutrition r/t decreased ability to digest foods AEB administration of Relistor, 8mg, INJ, subcut, every other day for weight 38kg or less than 62 kg, continuous infusion of amino acids 2.75%- D5% and electrolytes 1,000ml, IV, 80ml/hr, nutrition evaluation noting weight 2 months ago: 135 & current weight: 114.6lbs, albumin 3.4 (low), protein total serum 6.1 (low) and decreased appetite. Priority Assessments Clinical Concept Map Daily weight Intake and output Lung assessment (for adventitious sounds) Heart assessment (rhythm, rate, Signs for SOB, dizziness, etc) pain level monitor electrolytes abdominal assessment(bowel sounds, presence of gas, tenderness, pain) Assess surgical incision ( approximated edges, no redness, no drainage) Signs and symptoms of infection (fever, elevated WBC) Nursing Diagnosis Acute pain r/t surgical incision of abdomen AEB patient reporting 6/10 on pain scale after surgical procedure located in abdomen, mild abdominal tenderness, administration of 0.4 mg/ml, 40 mg dilaudad, IV, PCA, PRN lockout interval 10 PCA dose 0.2mg Expected Outcomes (2) Interventions with Rationale 1. The patient will verbalize a pain score less than a 3 on 0-10 scale by the end of the shift. 2. The patient will increase communication with the nurse of her pain level during hourly rounds by the end of the shift. Evaluation 1. The goal was met AEB the patient reporting a pain level of 0 with the administration of dilaudad by the end of the shift. 2. The goal was partially met AEB the patient did not communicate with the patient at the beginning of the day but by the middle of the day the patient communicated with the nurse hourly regarding her pain. Outcome #1 1.Determine if the client is experiencing pain. If pain is present, conduct and document a comprehensive pain assessment and implement pain management interventions to achieve comfort. Assess location, quality, onset/duration, intensity, aggravating and alleviating factors, and effects on function. Rationale: “Determining these characteristics are important in determining the underlying cause of pain and effective treatment” (Ackley, 2011, p.601). 2.Assess the pain level in the client using a valid and reliable self-report pain tool, such as the 0-10 numerical pain rating scale. Rationale: “The first step in pain assessment is to determine if the client can provide a self-report. Ask the client to rate pain intensity or select descriptors of pain intensity using a valid and reliable self-report pain tool” (Ackley, 2011, p.601). 3.Ask the client to describe prior experiences with pain, effectiveness of pain management interventions, responses to analgesic medications including occurrence of adverse effects, and concerns about pain and its treatment. Rationale: ”Obtaining an individualized pain history to identify potential factors that may influence the client’s willingness to report pain, as well as, factors that influence pain intensity, the client’s response to pain, anxiety, and pharmacokinetics of analgesics” (Ackley, 2011, p.602). 4.Administer opioids orally or intravenously (IV) as ordered. Provide PCA, perineural infusions, and intraspinal analgesia as ordered, when appropriate and available. Rationale: The IV route is preferred for rapid control of severe pain. For constant pain administer the opioid every 4 hours around-the-clock. For intermittent or breakthrough pain, prn dosing is appropriate” (Ackley, 2011,p.603). 5.Plan nursing care when the client is comfortable based on pharmacokinetics and the maximum serum concentration of the opioid. Rationale: “For opioids intravenously administered varies 6-10 minutes when the medication becomes effective. Knowing when the medications becomes effective helps guide nursing practice of checking back on the client, ensuring that adequate pain relief has been obtained, and also planning nursing activities” (Ackley, 2011, p.604). 6.Assess for the influence of cultural beliefs, norms, and values on the client’s perception and experience of pain. Rationale: “A study of African American elders found the use of prayer and faith for pain management very common” (Ackley, 2011,p.606). Outcome #2 1.Assess the client for pain presence routinely at frequent intervals, often at the same time as vital signs are taken, and during activity and rest. Also assess for pain with interventions or procedures likely to cause pain. Rationale: “Pain assessment is an important as physiological vital signs and pain is considered as the ‘fifth vital sign’. Acute pain should be reliably assessed both at rest and during movement” (Ackley, 2011, p.602). 2.Ask the client to identify a comfort-function goal, a pain level, on a self-report pain tool, that will allow the client to perform necessary or desired activities easily. This goal will provide the basis to determine effectiveness of pain management interventions. Rationale: “The relationship between pain level and functional goals should be a major focus of the development of individualized pain management plans (Ackley, 2011, p.602). 3.Determine the client’s current medication use. Obtain an accurate and complete list of medications the client is taking or taken. Rationale: “This history will provide the clinician with an understanding of what medications have been tried and were or were not effective in treating the client’s pain” (Ackley, 2011, p. 603). 4.Explain to the client the pain management approach, including pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions, the assessment and reassessment process, potential adverse effects, and importance of prompt reporting of unrelieved pain. Rationale: “One of the most important steps toward improved control of pain is a better client understanding of the nature of pain, its treatment, and the role the client needs to play in pain control” (Ackley, 2011, p.603). 5.Discuss the client’s fears of under treated pain, overdose, and addiction. Rationale: “Because of the many misconceptions regarding pain and its treatment , education about the ability to control pain effectively and correction of myths about the use of opioids should be included as part of the treatment plan. 6.Teach information about pain medications and their side effects and how to work with health care providers to manage pain, and encourage use of religious faith as desired to cope with pain. Rationale: “Socioeconomically disadvantaged African Americans clients benefit from educational interventions on pain and how to communicate assertively about their pain with their physicians and nurses. Nursing Diagnosis Dysfunctional gastrointestinal motility r/t surgery AEB hypoactive bowel sounds on assessment, placement of a Gastric Tube (NG tube), decrease of flatus, vomiting/nausea with clear liquids and absence of bowel movement. Interventions w/ Rationale Expected Outcomes (2) Outcome #1 1. The patient will have one bowel movement by the end of the shift. 2. The patient will be able to consume clear liquids without nausea and vomiting by the end of the shift. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Evaluation Inspect the abdomen, auscultate for bowel sounds noting characteristics and frequency, palpate, and percuss abdomen. Rationale: “Physical assessment of the abdomen can be helpful to find abnormalities or changes associated with either decreased or increased gastric motility” (Ackley, 2011, p.561). Evaluate medications the client is taking. Rationale:” Recognize that opioids and anticholinergics can cause gastric slowing” (Ackley, 2011, p.562). Review history noting any nausea/vomiting, abnormal characteristics of bowel movements, including frequency, consistency, and the presence of gas. Rationale: ”These are abnormal signs of gastric motility” (Ackley, 2011, p.561). Observe for complications of delayed gastric and or intestinal motility. Symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, cramping, anorexia, and sometimes bloating, abdominal distention, absence of flatus or bowel movements, and lack of bowel sounds. Rationale:” Documentation of these symptoms may indicate further intervention and assessment” (Ackley, 2011, p.562). Review diet history. Obtain nutritional consult, considering diets lower or higher in liquids or solids, especially fats depending on gastric motility. Rationale:” A patient may be advised to consume more fluids to promote bowel movement” (Ackley, 2011, p.562). Teach client and caregivers to report signs and symptoms that may indicate further complications including increased abdominal girth, projectile vomiting, and unrelieved acute cramping pain. Rationale:” These symptoms require evaluation by a physician to determine the underlying cause” (Ackley, 2011, p.564). Outcome #2 1. The goal was not met AEB patient having no bowel movement and passing small amounts of gas 2. The bowel sounds were hypoactive upon afternoon assessment. 2. The goal was not met AEB 1. The patient vomited broth and tea 2. The patient was put back on intermittent suction NG 3. The patient was prescribed supplementation for fluid and electrolyte loss via physician 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Monitor and record intake and output daily. Rationale: “GI dysfunction can cause rapid fluid loss, making it important to monitor” (Ackley, 2011, p.561). Assess for dehydration if client has continued nausea and vomiting, and to correct, provide an antiemetic and intravenous fluids as ordered. Rationale:”Recognition of complications of nausea and vomiting is critical to prevent and manage untoward complications of dehydration and electrolyte imbalance” (Ackley, 2011, 566). If client is unable to eat or retain food, consult with dietician and physician, considering further nutritional support in form of enteral or parenteral for the client. Rationale: “Some clients require supplementation to maintain electrolyte balance” (Ackley, 2011, p.562). Implement appropriate dietary measures such as NPO, small, frequent meals, and low fat meals. Also avoid fatty, spicy, or salty foods. Rationale:” Expert opinion consensus recommends these interventions” (Ackley, 2011, p.566). Consider nonpharmacologic interventions such as music therapy, distraction, and slow, deliberate movements. Rationale:”Nonpharmacologic interventions are easy to use, low cost, and have few adverse events” (Ackley, 2011, p.567). Provide oral care after the client vomits. Rationale: “Oral care helps remove the taste and smell of vomitus, and reduces the stimulus for further vomiting” (Ackley, 2011, p.567). References: Ackley, B.J., & Ladwig, G.B. (2011). Nursing diagnosis handbook: An Evidence-Based Guide to Planning Care. (9th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier O'connor, D.,B., & Winter, D. C. (2012). The role of laparoscopy in the management of acute small-bowel obstruction: A review of over 2,000 cases. Surgical Endoscopy, 26(1), 12-7. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00464-011-1885-9 Smeltzer, S.C., Bare, B.G., Hinkle, J.L., & Cheever, K.H. (2010). Brunner & Suddarth’s Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Nursing Process Concept Map Article Summary This article discusses laparoscopy in regards to managing acute small bowel obstruction. Laparotomy remains the standard approach with managing small bowel obstruction (O’Conner & Winter, 2012, p.12). A study was conducted to review the safety, feasibility, iatrogenic bowel injury and benefits for patients with condition treated laparoscopically. Acute small bowel obstruction (SBO) is common reason for emergency surgical admission. According to O’Conner & Winter, postoperative adhesions are the reason for surgery (p.12). Laparoscopy is beneficial in many ways. The technique reduces adhesions compared to laparotomy and results in shorter hospital stays. Peer reviewed articles pertaining to laproscopic approaches and the outcomes with small bowel obstruction procedures were retrieved and reviewed. Some patients were repaired laproscopically but most were converted to laparotomy (O’Connor & Winter, 2010, p.13). The most common reason for conversion to laparotomy included: dense adhesions, ischemic bowel requiring resection, and the inability to identify the pathology. The main advantages for laparoscopy or minimal invasive surgery are faster recovery, reduced morbidity and pain. It is appropriate to use in emergencies such as appendicitis and duodenal ulcers (O’Conner & Winter, 2012, p.13). In regards to feasibility, laparoscopy has a 64% successful completion rate (p.14). The overall mortality and morbidity rate for the procedure is 1.5% and 14.8%. The patient receiving laparotomy with small bowel obstruction had a recurrence rate of SBO 5-7% in the 1 year and 15% within 5 years. (O’Conner & Winter, 2012, p.14). Whereas laparoscopy proved to reduce adhesions and readmission for SBO. This information correlates with my patient because she did undergo an exploratory laparoscopy, exploratory laparotomy, lysis of adhesions, and release of small-bowel obstruction at Shawnee Mission. The laparoscope showed several markedly dilated small bowel loops and obvious inflammatory changes in the small bowel with multiple adhesions. In order to get a full evaluation of the bowel the surgeon felt it necessary to conduct a laparotomy. The adhesions were lysed with the laparotomy. Omentum adhered to the anterior abdominal wall was loosed with dissection of the adhesion. The laparotomy allowed better visualization of the small bowel loops. In my patient’s case the laparotomy more beneficial in diagnosing and treating the obstruction. The day I took care of my patient for clinical, she was five days postop. The incision site had no signs of infection. However, she was having a hard time recovering and producing a BM. My patient had a slower recovery rate and longer hospital stay. Following the laparotomy my patient was put on dilaudad prn to control the pain. The laparotomy resulted in longer recovery, longer hospital stay, use of narcotics to control pain versus the laparoscopy which results in shorter stays, recovery, and costs related to Faculty comment on Clinical Care Map Article Reference & Summary Faculty Comments: Faculty comment on Nursing Process Map