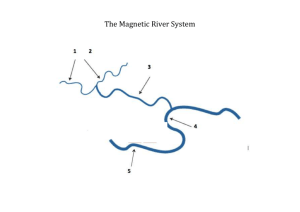

(CERAP) Christmas Hills Catchment

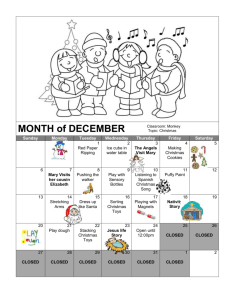

advertisement