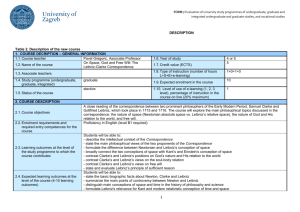

Master course Conceptions of space in the scientific revolution

advertisement

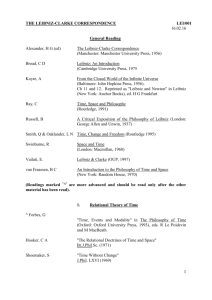

Master course Conceptions of space in the scientific revolution Semester I 2015-2016 Tuesday 16-18 One of the most persistent received views in the history of philosophy/history of science attributes the emergence of modern science to a change in the representation of space. It originates in the books of the iconic and influential historian and philosopher Alexandre Koyré. According to Koyré, the scientific revolution is the product of “two fundamental and closely connected actions”: the dissolution of the Aristotelian cosmos (the “closed world” of the ancients and medievals) and the “geometrization of space.” Thus, modern science began when Galileo and Newton started to do physics in the tri-dimensional, Euclidean space. As most of the other foundational stories of the Scientific Revolution, Koyré’s account has been repeatedly criticized and qualified. And yet, there is something fundamentally appealing in his connection between the fundamental breakthroughs of the early modern classical mechanics and the “geometrization of space.” It is intuitively compelling to think of “modern physics” as something taking place “in space” and of the universe of the moderns as consisting of infinite, homogenous, tri-dimensional space, in which bodies are placed according to the laws of mechanics and geometry. The purpose of this course is to rehearse some of the elements of this standard story by appealing to primary texts. Most of our meetings will be organized as reading groups. Students will be required to read and discuss, but also to make short presentations of the authors under discussion, as well as to analyze and comment primary and secondary sources. Objectives The course has two main objectives. First, I would like to investigate the diversity of competing conceptions of space in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. We will discuss to what extent these competing conceptions of space were also paired with different conceptions concerning the relations between physics (natural philosophy), mathematics and theology. Second, I would like to offer an alternative story to Koyre’s “geometrization of space.” My story will investigate how a science of space seemed to have emerged from discussions and debates over a cluster of natural philosophical concepts we would assimilate today to the notion of force. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries these concepts were called virtues or faculties, and were sometimes associated with minds, animal faculties or even souls. Course materials The course will primarily consist in reading, discussing and investigating primary sources. The list of reading contain some of the canonical texts of the scientific revolution (Galileo’s Dialogue, parts of Newton’s Principia, Descartes, Principles of philosophy, Berkeley, De motu) and some lesser known (or even completely unknown) texts belonging to William Gilbert, Thomas Digges, Giordano Bruno and Francis Bacon. Syllabus 1 Theme Required readings The standard story (1): Koyre’s interpretation Koyre, Chapters 1-3 of the interplay between metaphysics, astronomy and theology 2 The standard story (2): A “geometrization” or Primary source/text: a “materialization of space Galileo, Dialogue, Day I (fragments) 3 Koyre, Chapter 4 D. M. Miller, Introduction The end point of the standard story: the Newton, De gravitatione Newtonian absolute space. Newton’s scholium Newton, Principia, Scholium to the to the definitions definitions 4 5 6 7 Koyre, Chap. 5, 6 The early Copernicans: mathematics, physics Thomas Digges, A Perfect Description of and the metaphysical costs of the dissolution of the Celestial Orbs the celestial orbs Galileo, Dialogue, Day I (fragments) Secondary sources: Omodeo, Chap. 4 (supplementary: 2-4) The early Copernicans (II): metaphysics and Bruno, The Ash’ Wednesday Supper theology Secondary sources: Gatti, Giordano Bruno and the Renaissance Science, chapter 3 Gilbert’s magnetical philosophy and the Gilbert, De magnete, Book V (ch XI-XII), “science of the orbs themselves” Book VI (ch. I-III) Secondary readings: Gatti, Chapter 4 D.M. Miller, Chapter… Kepler’s celestial phyiscs: “a cosmological Kepler, Astronomia nova, Introduction rooftop on the magnetic philosophy” 8 9 The anti-vitalist philosophy programme: mechanical Descartes, Principles of philosophy, part II (4, 11, 12, 13, 15, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 29, 38, 39), Part III (28) Dealing with forces in the mechanical Kenelm Digby, Two treatises, (on the philosophy: Digby, Hobbes and various other magnet) programs of “mechanizing” the world picture 10 Galileo’s physics: the problem of force Galileo, Dialogue, Day II (fragments), Day III (fragments) Secondary sources : D.M. Miller, Chapter 11 Mutual interactions: forces in space Newton, Optical queries (on the bending of light rays), Principia (action/reaction, mutual gravitation) 12 Newton and the problem of action at a distance Newton’s letters to Bentley Leibniz Clarke correspondence 13 Back to Newton’s scholium to definitions: a philosophical conversation on absolute space 14 Concluding remarks Assignments Seminar presentation: introduce the author (30% of the evaluation) The seminar will begin with a 20 min presentation of the author whose text is under discussion. Students are required to choose one author and to prepare such a presentation, focusing on the context of the text for the seminar and the relevant details for its understanding. In introducing an author it is important to emphasize what was his general plan/project and how does our reading relate to that more general plan. Also, I would like to know more about the intellectual context in which our author’s ideas have developed, about his intellectual sources, friends and foes, about his successes (in his own time: was he read? Did he have students and followers?) and failures. Try to reconstruct a portrait as free as possible from the various biases of the various historiographies. Analyze a primary source (from the bibliography) (30% of the evaluation) Write a 4-6 pages ‘introduction to a primary source from the bibliography. Explain its main ideas, define its terms, place it in the context (among the author’s other writings, for example), provide the reader with the appropriate footnotes (definitions, explanations of terms, references to the background etc.) and the running commentary that would help her understand the text better. Final paper (30 % of the evaluation) Bibliography Koyré, Alexandre. 1958. From the closed world to the infinite universe. Library of Alexandria. Miller, David Marshall. 2014. Representing space in the scientific revolution. Cambridge University Press. Primary sources Newton, Scholium to definitions, General Scholium Newton, De gravitatione Descartes, Principles of Philosophy, Part II Galileo, Dialogue on the two world-systems, day I-III Gilbert, De Magnete, book V, ch. XII, book VI ch…. Kepler, Astronomia nova, Introduction The correspondence Leibniz - Clarke (http://www.newtonproject.sussex.ac.uk/catalogue/viewcat.php?id=THEM00224 ) (Leibniz 1 (1-4), Clarke 1 (1-3), Leibniz 2 (1), Clarke 2 (1), Leibniz 3 (1-7), Clarke 3 (2-8), Leibniz 4 (3-6, 7-11, 13-20, 41), Clarke 4 (all), Leibniz 5 (29-53, 60)). Francis Bacon, Theory of the heavens Bruno, The Ash’ Wednesday’s Supper… Berkeley, De motu (52-66) Secondary bibliography Freudenthal, Gad. 1983. Theory of Matter and Cosmology in William Gilbert's De magnete. ISIS 74 (1):22-37. Gatti, Hilary. 2002. Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Cornell University Press. Koyré, Alexandre. 1958. From the closed world to the infinite universe. Library of Alexandria. Miller, David Marshall. 2014. Representing space in the scientific revolution. Cambridge University Press. Omodeo, Pietro Daniel. 2014. Copernicus in the Cultural Debates of the Renaissance: Reception, Legacy, Transformation. Brill. Pumfrey, Stephen. 2011. 'Your astronomers and ours differ exceedingly’: the controversy over the ‘new star’ of 1572 in the light of a newly discovered text by Thomas Digges. British Journal for the History of Science 44:29-60.