Rescuing Malcolm X From His Calculated Myths

advertisement

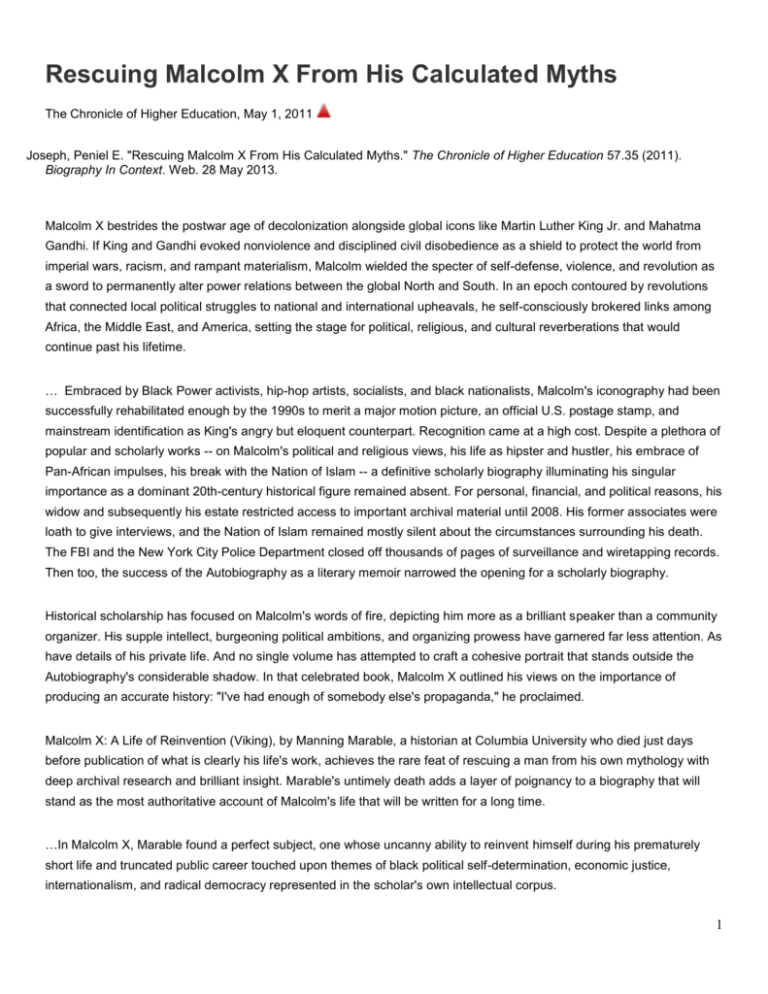

Rescuing Malcolm X From His Calculated Myths The Chronicle of Higher Education, May 1, 2011 Joseph, Peniel E. "Rescuing Malcolm X From His Calculated Myths." The Chronicle of Higher Education 57.35 (2011). Biography In Context. Web. 28 May 2013. Malcolm X bestrides the postwar age of decolonization alongside global icons like Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi. If King and Gandhi evoked nonviolence and disciplined civil disobedience as a shield to protect the world from imperial wars, racism, and rampant materialism, Malcolm wielded the specter of self-defense, violence, and revolution as a sword to permanently alter power relations between the global North and South. In an epoch contoured by revolutions that connected local political struggles to national and international upheavals, he self-consciously brokered links among Africa, the Middle East, and America, setting the stage for political, religious, and cultural reverberations that would continue past his lifetime. … Embraced by Black Power activists, hip-hop artists, socialists, and black nationalists, Malcolm's iconography had been successfully rehabilitated enough by the 1990s to merit a major motion picture, an official U.S. postage stamp, and mainstream identification as King's angry but eloquent counterpart. Recognition came at a high cost. Despite a plethora of popular and scholarly works -- on Malcolm's political and religious views, his life as hipster and hustler, his embrace of Pan-African impulses, his break with the Nation of Islam -- a definitive scholarly biography illuminating his singular importance as a dominant 20th-century historical figure remained absent. For personal, financial, and political reasons, his widow and subsequently his estate restricted access to important archival material until 2008. His former associates were loath to give interviews, and the Nation of Islam remained mostly silent about the circumstances surrounding his death. The FBI and the New York City Police Department closed off thousands of pages of surveillance and wiretapping records. Then too, the success of the Autobiography as a literary memoir narrowed the opening for a scholarly biography. Historical scholarship has focused on Malcolm's words of fire, depicting him more as a brilliant speaker than a community organizer. His supple intellect, burgeoning political ambitions, and organizing prowess have garnered far less attention. As have details of his private life. And no single volume has attempted to craft a cohesive portrait that stands outside the Autobiography's considerable shadow. In that celebrated book, Malcolm X outlined his views on the importance of producing an accurate history: "I've had enough of somebody else's propaganda," he proclaimed. Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (Viking), by Manning Marable, a historian at Columbia University who died just days before publication of what is clearly his life's work, achieves the rare feat of rescuing a man from his own mythology with deep archival research and brilliant insight. Marable's untimely death adds a layer of poignancy to a biography that will stand as the most authoritative account of Malcolm's life that will be written for a long time. …In Malcolm X, Marable found a perfect subject, one whose uncanny ability to reinvent himself during his prematurely short life and truncated public career touched upon themes of black political self-determination, economic justice, internationalism, and radical democracy represented in the scholar's own intellectual corpus. 1 Marable's subtitle, A Life of Reinvention, succinctly captures his book's larger effort to recast the political and personal life of the Black Power icon in both subtle and surprising ways. The Malcolm X revealed in these pages is at once a largerthan-life figure and a scaled-down, even frail human being. Marable refuses to shy away from Malcolm's flaws, candidly discussing his sexism, errors in political and personal judgment, and occasional anti-Semitic utterances. …. Years in the making, Malcolm X is a thoroughly researched biography, mining a rich archive of primary sources (including many never accessed before) and collecting oral histories from Malcolm's associates and Nation of Islam officials (most notably Louis Farrakhan). Marable's discussion of Malcolm's at-times strained marriage relies on such oral histories and on personal correspondence from Malcolm to Elijah Muhammad, his mentor and the Nation's spiritual leader, which offer substantive evidence of a troubled union. That's also the kind of material undoubtedly painful for surviving family members. … Racial politics formed part of Malcolm Little's birthright, an inheritance from his parents, Earl and Louise Little, two politically courageous supporters of Marcus Garvey -- or, depending on your perspective, ill-fated pioneers of black nationalism -- in the distant outpost of Omaha, Neb., where Malcolm was born on May 19, 1925. While Malcolm was still young, the family moved to Lansing, Mich. His was a difficult childhood, plagued by bouts of domestic violence, harassment from the local Klan, and Earl's gruesomely suspicious death (he was cut nearly in two by what white authorities claimed was a streetcar accident and Malcolm surmised was part of a lynching). Earl Little's death shattered his surviving family, hurling them into an emotionally fatiguing battle with state relief agencies that found the young Malcolm relying on foster care and eventually triggered Louise's mental breakdown and institutionalization. By 1941, Malcolm had moved to Boston to live with his older half-sister Ella. It was here that Malcolm Little first reinvented himself as a small-time hood whose crimes were at least partially inspired by Ella's own extralegal activities in pursuit of a middleclass lifestyle. Marable deconstructs the the Legend of Detroit Red outlined in the Autobiography, finding that Malcolm purposely exaggerated his criminal exploits as a way of obscuring painful and embarrassing memories and of emphasizing the importance of the Nation of Islam in his eventual transformation. Far from being aligned with major gangsters, in this period Malcolm alternated between part-time legal employment like selling food on railroads (where he was known as Sandwich Red), dealing small amounts of marijuana to jazz musicians, and engaging in largely amateurish holdups, at least one of which ended in an early arrest. Successfully evading the draft by feigning mental illness, Malcolm engaged in escalating drug abuse and petty crime that ended abruptly shortly after World War II. Arrested in 1946 for a series of burglaries, fooled by false promises of leniency, he turned in his whole crew. The interracial makeup of the burglary ring, which included Malcolm's white girlfriend, inspired a harsh sentence of eight to 10 years. Within the walls of Norfolk Prison Colony, in Massachusetts, Malcolm Little would reinvent himself again. Through letters from his brother Reginald, he was first introduced to the Nation of Islam, a religious nationalist sect whose emphasis on pride, self-respect, and discipline echoed his father's distant Garveyite preaching. Newly energized and clean and sober, Malcolm dove into a meticulous study of religion, history, and philosophy. Paroled in 1952, he quickly became a full-time Nation of Islam minister. Whereas Garvey resurrected ancient African kingdoms as proof of black nobility and self-respect, the Nation of Islam touted religious prophesy through an imaginative blend of Islam, black nationalism, and religious mythology that identified whites as "devils" and predicted America's destruction even as it embraced a conservative economic vision of black capitalism. 2 Reborn as Malcolm X, a surname that reflected black people's loss of identity in America's racial wilderness, the former Detroit Red now embraced personal self-discipline and an ascetic lifestyle. "The trickster disappeared," writes Marable, "leaving the willful challenger to authority." The biography weaves in new details to flesh out the narrative of Malcolm's becoming a minister and his rise to power within the Nation of Islam. He was an indefatigable organizer, whose remarkable ability to inspire new converts and recruits helped propel the Nation's tiny infrastructure into a formidable group with global ambitions. … Marable takes pains to illustrate that the iconography in Haley's Autobiography at times presumptuously crafted an image of Malcolm in line with Haley's own political views as a liberal Republican -- and one apt to sell commercially. The Autobiography sanitized Malcolm's radical politics by tacking on an introduction by a New York Times writer and an epilogue by Haley himself, even as it excised three chapters originally designed to showcase Malcolm's new political philosophy. … More than 45 years after his death, we now have a historical portrait of Malcolm X that goes beyond literary cliches and autobiographical fictions to reveal an all-too human man beset by personal trials and political tribulations that would have felled the less courageous. Stripped from the cocoon of his posthumous aura of invincibility, Malcolm X emerges from these pages an endlessly fascinating and protean figure whose shortcomings make his political accomplishments all the more remarkable. Against the backdrop of private disappointments and embarrassingly public betrayals, Marable reminds us that Malcolm X still managed to transform "the discourse and politics of race internationally," a final enduring reinvention that continues long after his death. 3