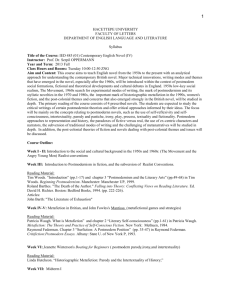

Week 8 – Writing Historical Fiction

advertisement

GU Creative Writing Society 2014 Week 8: Writing Historical Fiction Points of interest: Aiming for realism? Accuracy: getting your facts right. Can you think of any examples of literature that succeeds or fails here? Mood: how are you going to capture what it felt like in this period? Dialect, accent, language: rather than engaging in lengthy descriptions of the character which verge upon an encyclopaedic narrative, try establishing them through dialogue Clothes, architecture, technology and other objective details – the little things count in giving your reader a sense of authenticity Educating readers: how are you going to write without falling into the trap of attempting to ‘educate’ your reader about the historical period Using research: you may have compiled a ton of information on the Mayans, or evacuees during WWII. That doesn’t mean you have to use all your facts and details; think of them as a kind of bank upon which you can draw if you need to, but also which sits in the back of your mind and helps you unconsciously when you write, shaping your tone and descriptions to the stuff in your research Establishing setting: it might help to reference real places, like street names, cities, parks, train lines Using real life characters: it might be interesting to take famous characters from history and fill in the gaps of their lives, things you didn’t know about. These might be weird, unexpected things which you can take as a kernel for your narrative and then build upon: a suffragette with an addiction to shoplifting, the secret life of George Washington’s dogs, the illicit affairs of Aristotle, Marx’s guilty pleasure of online gambling (okay, that one is probably anachronistic – but that’s something you should watch out for, unless you’re deliberately meshing together things from different time periods). Textuality: might it be useful to intersperse your text with ‘authentic’ documents: fragments of diary entries, letters, stamps, a piece of a discoloured map? Tip: go through a historical novel and pick out details about the time period. How does the author ‘show’ them rather than ‘telling’ them? (Dialogue, setting etc). Can you use similar techniques in your own writing? Encyclopaedic fiction: a work of fiction which employs a variety of forms to explore its subject exhaustively. For example, novels that include lectures on particular topics, extracts from other non-fiction texts, historical artefacts etc. Relating the past to the present: Perhaps try imagining the past as a prologue to the present rather than a self-contained moment in history. How might the characters in your novel imagine the future? For example, in Tom McCarthy’s C, one character, who works with telegraphs, says that one day, “there'll be a web around the world for them to send their signals down", thus predicting the internet. The Historical as discourse/text: Realism is all very well and good, but after all we know the past only through history, which tends to be written. And where writing is concerned, bits of fiction, manipulations of the GU Creative Writing Society 2014 ‘truth’ creep in. History, they say, is always written by the winners. But what does this actually entail about how we conceive of our past and its impact on the present? How can fiction play with the subjective nature of historical narrative? Are you going to foreground the discursive nature of history (something constructed in discourse rather than an objective knowledge) or are you going to attempt to mime a historical ‘reality’? Linda Hutcheon’s ‘historiographic metafiction’: ‘What historiographic metafiction challenges is both any naive realist concept of representation and any equally naive textualist or formalist assertions of the total separation of art from the world’ (Linda Hutcheon) ‘Histiographic metafiction is particularly doubled […] in its inscribing of both historical and literary intertexts. Its specific and general recollections of the forms and contents of history writing work to familiarse the unfamiliar through (very familiar) narrative structures […] but its metafictional self-reflexivity works to render problematic any such familiarisation’ (Linda Hutcheon). Key points: intertextuality, pastiche of registers and modes of discourse (historical, pop culture, fiction, fantasy etc), metafiction (texts that foreground/reflect their own textuality), postmodern scepticism of ‘truth’ Some useful advice: ‘It goes without saying that you’ve researched your historical facts, and that includes manners and morals as well as stage-coaches and corsetry: how people behave in matters of sex or smoking must be as accurate and convincing as how they cook or bet or fight. You’ve kept a sharp eye out for things you didn’t know you had to check: don’t make your medieval peasants eat potatoes or your Regency heroine tell her fiancé to ‘step on the gas’, and don’t forget that everyone always wears a hat outdoors. You’ve read writing of the period and found a voice for your novel that’s neither incomprehensible, nor twee pastiche, nor crashingly modern. And then you must leave it all behind, because you’re not writing history, you’re writing fiction, and fiction is all about what you can make the reader believe you know: not what you’ve learnt in a library, but what you know as naturally as you know your own house. The worst writing you’ll ever do is what you write when you’ve got a history book in the other hand. The best is when your characters and their points of view are so alive to you that of course you write what they see and how they see it, their voices filling that panelled room or smoky alehouse. And all of that must happen without you once letting the reins drop. Your readers want to live and breathe history but they won’t keep reading if the narrative grinds to a halt on a hill of historical detail. So find it all out, get it right, and then, in a sense, forget what you’ve found and write. You’re telling stories, not histories’ (Emma Darwin) http://www.historicalnovels.info/Writing-Historical-Fiction.html. Exercise [individually or in pairs/groups]: GU Creative Writing Society 2014 1) Pick a historical figure and attempt to reimagine a scene from their life. (Here are some ideas to get you started: Henry VIII, Marilyn Monroe, Virginia Woolf, Churchill, Hitler, Marie Curie, Leonardo Da Vinci). OR 2) Pick a particular time and place in history and write a scene set within it. Further Questions to consider: How successful have you found historical novels in evoking the past? What literary elements do they employ to effect this? What television dramas/films could be classed as historical? To what extent do they recreate the feel of the period, or do they feel too self-indulgent? Consider the popularity of the ‘costumer drama’: why do people like watching these things? How can you appeal to readers’ desire for a nostalgic, prettified or indeed goreified past? Titanic, Braveheart, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, Pride and Prejudice, Gone With the Wind etc. Some good examples of historical fiction and/or historiographic metafiction: Ian McEwan, Atonement Alasdair Gray, Poor Things John Fowles, The French Lieutenant’s Woman Margaret Atwood, Penelopiad (rewriting the Greek story of Penelope: historical fiction as feminist rewriting) Hilary Mantel, Bring up the Bodies Sir Walter Scott, The Waverley Novels Tom McCarthy, C