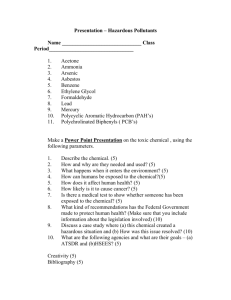

Full Report (Word 252KB)

advertisement