Guidelines for the Depreciation of Library Collections. 2010

advertisement

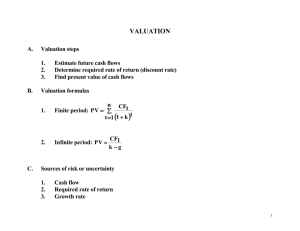

Guidelines for the Depreciation of Library Collections February 2010 Public Libraries Victoria Network Depreciation of Library Collections - Guidelines 1. 1.1 Purpose of the Guidelines Background and Context The purpose of the guidelines is to provide a framework, guidance and assistance for library managers, finance staff and boards in Victoria’s public libraries in determining their approach to the calculation of depreciation expense in relation to library collections. The need for the guidelines has emerged as a result of research that identified large variations in the methods applied in the determination of depreciation for collections. Whilst a level of variation methods and rates is inevitable, this was seen to be compromising the capacity of the financial reports of library services to convey reliable and consistent messages to users and stakeholders about financial performance of libraries and the manner in which resources are being consumed in relation to library services. In the process of developing the guidelines, it has also emerged that there is a need for explanation and information about depreciation in a format that is more accessible to library professionals and staff, as well as for finance professionals in local government and regional library corporations. In particular, the guidelines seek to address the relationship of depreciation expense to the capital budgeting functions of libraries (commonly known and the ‘bookvote’). The reason for this is to equip library professionals with information about the nature of depreciation and how it works to aid them in the processes of managing the financial affairs of libraries including the preparation of annual operating and capital budgets. 1.2 Application of the guidelines The guidelines are for the provision of advisory information and general guidance to library board members, staff and professionals. The guidelines provide general information only. They should not be seen as overriding any specific financial advice provided to libraries. The guidelines have been prepared to convey to people working in the Victorian Public Library Sector what is considered to be best practice in relation to the determination of depreciation rates. In providing the guidelines, it is acknowledged that the specific business context of each library takes primacy over any need for industry consistency or adherence to library sector standards. In preparing the guidelines, input and advice has been provided by the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, the Department of Planning and Community Development, library finance professions and librarians. Mach II Consulting Page 2 Public Libraries Victoria Network Depreciation of Library Collections - Guidelines 2. Depreciation - A ‘Non-Accounting’ Explanation 2.1 A ‘Non-Cash’ Expense Depreciation is a ‘non-cash’ expense recorded in the financial accounts of public libraries. It is essentially an artificial accounting mechanism that adjusts to the simple ‘cash in/cash out view’ of library operations. The objective of this mechanism is to provide a better ‘resourceconsumption’ and ‘benefit delivered’ view of library operations. Depreciation adjusts the cash record of the business to align or match when resources or value is shown in the financial statements as being consumed to when the benefit is actually delivered. Depreciation is the accounting mechanism that aims to match a share of the cost of assets to each year that it will deliver benefits. It spreads the costs for major expenditure items that are deemed will deliver benefits to the organisation beyond the current year (assets) over the life of the assets. In effect, it smooths out bumps (distortions) in the bottom line impact (or operating result) that major expenditure items would otherwise create (if they were charged to the operating statement in the year of acquisition), distorting the view that the financial reports create for readers in a given year. The rationale for applying this mechanism is to provide members and stakeholders with a picture of financial performance in any given year where resources consumed and benefit derived are better ‘matched’. 2.2 ‘Capitalisation’ In public libraries, depreciation was first brought in with the introduction of full accrual accounting in the early-1990s (Australian Accounting Standard 27). This accounting standard required ‘assets’ to be ‘capitalised’. Assets generally include larger physical items that have the potential to deliver ongoing value or benefit (land, buildings, plant and equipment, etc.). However, for accounting purposes, assets do not have to be physical or large: they can include anything where the benefit is expected to last beyond the current year. To ‘capitalise’ an item of expenditure means to treat it as an asset in the accounts. That means recording it in the balance sheet rather than in the operating statement. The implication of capitalising an item of expenditure (i.e. treating it as an asset and putting it on the balance sheet) rather than ‘expensing’ it is that it is a recognition that the value and benefit from that expenditure will flow not only in the current year, but also in future years. Alternatively, if an expenditure item is ‘expensed’ and recorded in the operating statement (i.e. not treated as an asset and capitalised), the underlying assumption is that the value or benefit flowing from the expenditure will be totally consumed within the current year. Mach II Consulting Page 3 Public Libraries Victoria Network Depreciation of Library Collections - Guidelines Most library collection items have a useful life of more than one year. In this context, collections are required by the Accounting Standards to be capitalised. To the extent that the value or benefit embodied in those assets is ‘finite’ (i.e. it has a limited useful life), and it does not increase in value or retain value (i.e. like land), collection items are regarded as ‘depreciable’ assets. That means the benefit embodied in them is finite and it will, over time, be consumed and so they are required to be depreciated in the library accounts. Depreciation is the artificially calculated expense that represents that part of the capitalised cost of the asset that is attributable to a particular year. The definition of the depreciable amount of an asset’s value is its cost, less its residual value. In determining the depreciation expense, the estimated useful life of the item is the key consideration. 2.3 Library Collections are ‘Category Assets’ Most libraries and councils include a ‘capitalisation threshold’ in their accounting policies. This means that even though certain things (like staplers, coffee cups etc.) could be regarded as assets in a technical sense (ie; they have ongoing value that will last more than 1 year), for practical reasons these are not treated as assets for accounting purposes if they fall below a defined monetary capitalisation threshold (say $500 or $1000). This is a practical measure that ensures that accounting energy is not wasted on keeping accounting records for insignificant items and matters. Typically, if library collection items were treated individually, most would fall below such thresholds and not be capitalised. However, together, collection items do form a significant category item or asset class: they are truly a core asset of the library service that is significant to the business. Hence, collections are generally treated as category assets. That means they are accounted for and depreciated as a group (or sub-groups) rather than individually. Mach II Consulting Page 4 Public Libraries Victoria Network Depreciation of Library Collections - Guidelines 3. Guidelines for Depreciation - A ‘Best Practice’ Approach 3.1 ‘Entity Context’ is Paramount In defining the depreciation method, rates and useful lives for your library collection, it is your own local business context that is paramount. In other words, in determining your approach and rates, the primary consideration should be what is the impact on your entity. Accountants and auditors will consider the principal of ‘materiality’ in looking at depreciation methods and rates and different asset classes. Materiality generally refers to the significance of an item or issue in your own local business and operating context. Something regarded as a small or immaterial item or asset in one library context may in fact be very significant and material in the context of a smaller library. Similarly, the nature, collection profiles, number of borrowers and operational/service profiles of different libraries varies significantly. For this reason, it is not possible to come up with a single (standard) set of rules regarding depreciation methods and rates. The guidelines therefore provide guidance only - all local policies need to be developed to reflect the operating context of your library. 3.2 Basis of Recognition In a library context, accounting standards require assets to be recognised ‘at cost’ or, where donated or acquired at no or nominal cost, at ‘fair value’. Best practice is to recognise collections at original cost and then continue to carry them at original cost less accumulated depreciation. It is recommended that costs associated with acquisition viz cataloguing, processing, etc. are treated as operational expenses and not capitalised. The allocation of these costs would be in many cases problematical. Technically, a library may elect to carry assets after initial recognition by applying the ‘revaluation model’. This involves revaluing the asset at ‘fair value’ where that can be reliably determined. The revaluation model is not considered relevant in a library context. 3.3 Residual Value The total depreciable amount of an item (or group of collection items) is defined as the cost less the estimated residual value. Whilst in practical terms, library items may sometimes be sold in stalls and markets as well as discarded or destroyed, for accounting purposes this would generally be regarded as ‘immaterial” (or insignificant in the context of the library operations). Therefore, for the purposes of depreciation, the residual value of collection items would normally be defined as nil. Mach II Consulting Page 5 Public Libraries Victoria Network Depreciation of Library Collections - Guidelines A simple worked example of depreciation using a nil residual value is shown below: Original Asset Cost: $100 Less: Residual Value: = DEPRECIABLE AMOUNT: $0 $100 Estimated Useful Life: YEAR 1 YEAR 2 Depreciation Expense (P & L): Carrying Value (Balance Sheet) $20 $80 $20 $60 5 years YEAR 3 YEAR 4 YEAR 5 $20 $40 $20 $20 $20 $0 The implication of assuming a nil residual value is that the whole of the original cost of the asset is deemed to be consumed over its defined useful life through the depreciation expense charged to the profit and loss statement. 3.4 Defining ‘Useful Life’ Defining the ‘useful life’ of an asset for the purposes of depreciation is not a precise science. It is very subjective. The estimated useful life defines the rate of depreciation. As a general rule, estimated useful lives defined for the purposes of depreciation should as close as possible reflect the actual usage profile of different categories of items in your collection. As stated, this is library-specific and will vary from library to library. It is possible that an identical collection item could have a different useful life in 2 different library contextsDifferent types of items (reference, fiction, DVDs etc.) have very different usage patterns, differing levels of physical durability and therefore different useful lives. In Australian Accounting Standards ‘useful life’ is defined in terms of “... the asset’s expected utility (or usefulness) to the entity.” The standards also recognise that the useful life of an asset to your library may be different to its actual or economic life. Accounting Standards therefore recognise that useful life for depreciation purposes is a matter of judgement based on the experience of your library rather than an industry standard. The issues to be considered in defining useful life include: Mach II Consulting The level of usage that typically applies to that type of item; The physical wear and tear that results from that use; The technical and commercial obsolescence – the currency or ongoing relevance of the content embodied in the items; and The Library’s collection management policy, cull periods that apply to items in each category and any legal or other limits on usefulness that might apply. Page 6 Public Libraries Victoria Network 3.5 Depreciation of Library Collections - Guidelines Establish an ‘Evidence-Base’ Given the subjectivity in defining the useful life of collection items, it is ultimately an assumption-driven process. Therefore, ideally, an evidence base should be established to support your useful life assumptions. There are 2 methods that can be applied: Option 1: Borrowing Profile by Sub-Category Your library management system provides the best evidence base for your collection’s actual borrowing and usage profile. Usage profiles for different collection categories can be used to define your useful life and depreciation rates. This evidence base also provides a rational basis for discussions with audit committees and auditors regarding how depreciation rates and methods have been determined. Following is a theoretical usage profile for a collection item category (nonfiction). ‘USEFUL LIFE’ RANGE USAGE PROFILE - NON-FICTION No. OF LOANS 1 YO 2 YO 3 YO 4 YO 5 YO 6 YO 7 YO 8 YO AGE CATEGORY (Years Old) - NON-FICTION This example shows how the usage level (borrowing rate) ‘tails off’ (for this collection category) for items when they reach an age of 5 to 6 years. Assuming it remains on the shelf after that, usage would stay at a low level. Otherwise, it would cease upon being removed from circulation. This borrowing profile could be used to support a depreciation policy assumption that defines the ‘useful life’ at around 5 or 6 years. But, as can be seen in this example, it is by no means conclusive or definitive. Similarly, this usage profile could be used to determine the library’s target discard/cull policy of say 6 years and this, in turn, defines the assumed useful life for depreciation purposes. Usage profiles for other collections items may look very different to this example profile. In any case, the practical ‘usefulness’ of a library item does not just ‘switch off’ after a given number of years. In practical terms, actual use may continue on after the theoretical useful life (assumed for the purposes of depreciation) has expired and the item has been totally written off in the financial accounts of the library. This of course assumes it remains in circulation. There are no hard and fast rules to defining useful life for different types of collection items. However, it is best practice to apply some logical evidence-based method. The ability to do this is, of course, depends on the capability of the library management system. It is such an evidence base, that reflects the operational reality of the library, that auditors will look for in considering the appropriateness of the depreciation assumptions you use. Mach II Consulting Page 7 Public Libraries Victoria Network Depreciation of Library Collections - Guidelines Option 2: Discard/Cull Rate Based (by Sub-Category) As stated, you can use such borrowing profile data to determine your library’s adopted discard/collection cull rates which in turn becomes the basis for your depreciation rates. The discard/ cull rate is simply the number of discarded/culled items in each collection category as a percentage of the total number of items in each category, as shown below: Collection Item: Sub-Category Fiction No. of Discarded Items p.a.: Total. Items Discard Rate Implied Useful Life 1,200 9,000 13.33% 7.5 years 13.33% p.a. A variation of this approach using discard/collection cull rates is to calculate a weighted average cull/discard rate and accompanying depreciation rate across the whole collection. ... equates to a depreciation rate of : 3.6 Depreciation Methods Straight-Line Method: The above example applies the ‘straight-line’ method of depreciation. This means a collection category is depreciated by a fixed $ amount each year calculated by dividing the total depreciable amount by the estimated useful life. This method is regarded as an appropriate method for libraries where ‘value’ is consumed is a generally consistent manner over the asset’s life. Diminishing Value Method: An alternative to the ‘straight-line’ method of depreciation is the ‘diminishing value’ method. This means a collection category is depreciated by fixed percentage of the remaining book value each year. Under this approach, the percentage still needs to reflect an underlying useful life estimate over which the asset will be written off. This method is also regarded as an appropriate method for a library situation. A comparison of these 2 methods is illustrated below: $ Book Value (WDV) $100 $0 ‘Straight-Line’ Method: Written Down Value ‘Diminishing Value’ Method: Written Down Value Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 This graph shows how, under the diminishing value method, higher levels of depreciation expense are incurred in the earlier years of an asset’s life compared to if the straight-line method were applied. Mach II Consulting Page 8 Public Libraries Victoria Network 3.7 Depreciation of Library Collections - Guidelines Cultural/Heritage/History Items In a library collection context, some items, having gone through their normal utility cycle (and presumably having survived culling), can eventually take on a different ‘value’ to the collection which bears no relationship to its original use or its utility. Many library collections include items deemed as having cultural or heritage significance and local history collections. Generally, cultural or heritage items, whilst treated as assets and included as part of the collection on the balance sheet, would not be regarded as depreciable and therefore not depreciated. In the case of these assets, a fair book (or carrying) value in monetary terms still needs to be determined. This can be difficult and is very subjective given the ‘non-utility’ nature of heritage and cultural assets. In these cases, items can sometimes (and often do) appreciate, in which case it becomes appropriate to revalue the assets. In these cases, specialist expert advice is necessary to determine appropriate and fair values for cultural and heritage collection items. Collection items that fall into this category are generally those that are deemed to have significant ongoing value that is not going to be consumed or exhausted through use or over time. 3.8 Indicative Collection Sub-Categories and Useful Lives The table on the following page provides indicative categories/classes for a library collection. Also shown is an indicative useful life range for each collection sub-category which may be used. Actual useful life of a collection category deemed to apply in your library context may be outside the indicative ranges shown. Similarly, you should apply categories that reflect your own collection profile and management system. Mach II Consulting Page 9 Public Libraries Victoria Network Depreciation of Library Collections - Guidelines Collection Item: Sub-Category Indicative Useful Life Range Depreciation (% p.a.) 1. Fiction 5-8 years 20% to 12% 2. Non-Fiction 5-8 years 20% to 12% 3. Paperbacks 5-8 years 20% to 12% 4. Picture books/junior 5-8 years 20% to 12% 5. Reference 6-10 years 18% to 10% 6. Talking books 5-7 years 20% to 14% 7. DVDs/Videos/CDs /Cassettes 3-5 years 33% to 20% 8. Periodicals (Note 1) 2-3 years 50% to 33% Indefinite No 10. Newspapers/magazines 1 year No 11. Annual subscriptions - data-bases, resources & E-books (Note 3) 1 year No Capitalise and Depreciate: Capitalise and Non-Depreciable: 9. Local history/cultural/ heritage (Note 2) Expense: Notes: 1. Some periodicals may be retained & deemed to have a useful life beyond 1 year. 2. Cultural and heritage collection items – see section 3.7 above. 3. Where subscriptions to web-based and electronic resources, data-bases, E-books and similar items provide rights of usage for up to 1 year, these would generally be expensed. This includes situations where a subscription fee is paid annually even if it is as part of a longer-term agreement or contract that the library is party to. In the event that a subscription payment provides usage rights for a period of longer than 1 year, these may be capitalised. Mach II Consulting Page 10 Public Libraries Victoria Network Depreciation of Library Collections - Guidelines 4. Depreciation and Collection Re-Investment - The ‘Bookvote’ 4.1 Is there a link? In technical or accounting terms, there is no direct link between depreciation expense and the level of the bookvote. Links can be drawn between the two whereby there is a relationship between the level of capital funds allocated for collection revitalisation (ie; the ‘bookvote’). Such comparisons are generally made at a ‘macro’ level in relation to overall financial sustainability where the level of depreciation can be seen as an indicator of the asset reinvestment effort by the library. The Victorian Auditor-General’s Office has included such indicator data (‘collection investment gap’) in reporting on the financial sustainability of regional library corporations in recent annual reports on Local Government audits. Depreciation is a retrospective accounting mechanism that relates to the costs of past asset use and activities. ‘Bookvote’, on the other hand, is a forward-looking capital budgeting activity – it should be primarily governed by strategic planning, collection development planning and identified needs, rather than accounting issues such as depreciation. The relationship is described below: Mach II Consulting Depreciation ‘Bookvote’ – Accounting/reporting: - Capital budgeting/planning: Retrospective accounting mechanism – technical process driven by accounting standards/regulations. The non-cash expense associated with the using up of value in existing collection items. Method of depreciation and useful life should be determined based on evidence-base around actual use. Should be apolitical. Reflecting the entity is the focus, not the sector. Capital budgeting process - forwardlooking budgeting function. Not governed by accounting standards and regulations. The amount of funds that may or may not be allocated to replace collection items or revitalise/add to the collection. Political process – RLC boards/councils may set aside funds as they see fit. Method of determination should be based on need, strategic directions and priorities and funds available. Can be influenced by sector benchmarks (i.e. 2 collections items per capita, collection capital investment per capital etc.) Processes applied may be subject of attention through audit processes. Page 11 Public Libraries Victoria Network Depreciation of Library Collections - Guidelines So, while there is no direct technical link, in practical terms, some councils/RLCs may look to the amount of depreciation expense in a given year to provide some guidance in determining an appropriate amount of funds to be set aside through the ‘bookvote’. It is sometimes used by councils/RLCs as a ‘floor amount’ in defining bookvote or as a prima-facie indication of an amount that is at least required to be invested in collection rejuvenation to maintain existing service levels. However, caution needs to exercised with such an approach so as to ensure that it does not inadvertently contribute to or aggravate misunderstandings about the relationship between these two separate processes. Further, given that depreciation expense is calculated on the actual historical cost of existing collection items (rather than estimates of future costs), it could reasonably be considered that even where a level of ‘bookvote’ is equal to 100% of depreciation expense, this is tantamount to a decline in collection quality and service levels in real terms. The amount of depreciation expense does not necessarily reflect the real needs of the collection in the library’s overall strategic context. Nor will it provide an accurate indication of the likely cost of rejuvenating the collection or responding to changing community demand and information needs. This is especially the case where here depreciation rates are based on historical costs of old items rather than replacement costs of future items. Best practice is to apply a range of indicators to a forward-looking, needs based ‘bookvote’ process. This includes: library sector benchmarks (such as the number of collection of items per capita, the level of revitalisation investment per capita); the strategic outlook for your library, its chosen product offering and the service level priorities of your council/RLC; community views and consultation outcomes in relation to your library and its services; and total capital funds available. Similarly, the relationship between collection investment levels and depreciation levels (the collection investment ‘gap’) can also be used as an indicator for capital budgeting/planning purposes but should not be viewed in isolation. 4.2 Summary An overriding principle that should apply in the whole depreciation consideration is that of common sense. Everything about depreciation relates to estimating and assumptions and it needs to be seen in this rather than a precise context. In the interests of public accountability, there needs to some rational evidence bases to support depreciation assumptions. It is important to identify an approach to depreciation that meets the technical accounting requirements, offers a reasonable basis to attribute cost to where and when benefits flow and is reasonably simple for library professionals to administer and understand. Mach II Consulting Page 12