Group 2: Hippotherapy - University of Colorado Denver

advertisement

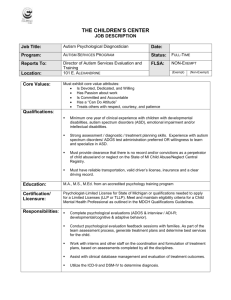

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Hippotherapy on Social Functioning for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Caiti McDaniel MS, OTR/L Beth Hoesly MS, OTR/L Candy Tefertiller, PT, DPT, NCS Katia Hannah, CPH 2 Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are a group of developmental disabilities characterized by restricted or repetitive behaviors and deficits in communication and social interaction. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that one out of every 88 children born in the United States today will be diagnosed with ASD (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). This report also found that the prevalence rate rose by 78% from 2002 to 2008, and is estimated to continue rising. Therefore, more and more children and their families are affected by this disorder every year. ASD has profound effects on the child’s development and quality of life. One particular area of development that is affected by autism is social functioning. Children with ASD demonstrate impairments in social orientation and attentional distress—the instincts to spontaneously pay attention to social stimuli and display sensitivity to another’s emotional cues (Dawson et al., 2004). Additionally, young children with autism do not engage in joint attention—defined as the sharing of attention with others through showing, pointing, and coordinated looks between objects and people—as often as typically-developing children (Charman et al., 1997). All of these deficits in social interaction skills have implications for the child’s social participation. Preschool-aged children with ASD have been found to be less likely to socially interact with their peers than typically-developing children (McGee, Feldman, & Morrier, 1997). In a study evaluating teenagers with autism, the authors found that adolescents with ASD were significantly more likely than their peers with other disabilities to be socially isolated, never to see or get called by friends, and never to be invited to activities (Orsmond, Shattuck, Cooper, Sterzing, & Anderson, 2013). 3 While there is no cure for ASD, there is evidence that early intervention can decrease symptoms and enable the child to thrive throughout the lifespan (e.g. Dawson & Osterling, 1997; Karanth & Chandhok, 2013; Klintwall, Eldevik, & Eikeseth, 2013). Children with autism typically receive a variety of therapeutic services to promote their health and well-being, including: occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech-language therapy, and behavioral therapy. These therapies typically take place within an outpatient medical environment, the school environment, or in the home. One emerging therapeutic technique for children with autism involves providing therapeutic services using a horse in an equine environment. The American Hippotherapy Association (AHA) defines hippotherapy as “the incorporation of equine movement by physical therapy, occupational therapy, or speech language pathology professionals in treatment. These professionals use evidence-based practice and clinical reasoning in the purposeful manipulation of equine movement to engage the sensorimotor and neuromotor systems to create functional change in their patient” (AHA, 2015). A recent study found that 11% of parents of children with an ASD report utilizing hippotherapy or other equine interventions for their children (Thomas, Morrissey, & McLaurin, 2007). Despite the growing use of hippotherapy, there is little evidence to support its beneficial effect for children with autism. A systematic mapping review of 35 years of peer-reviewed literature only located three articles that investigated the effects of hippotherapy specifically for children with autism (Wood, McDaniel, & Hoesly, 2015). Using a single-subject design, Taylor et al. (2009) demonstrated that 16 weeks of hippotherapy increased volition during play of three children with autism. Similarly, Tabares et al. (2012) used a single group pretest-posttest design to demonstrate that four hippotherapy sessions altered the hormone levels (cortisol and progesterone) of boys with ASD in a manner that suggests an improvement in social attitudes. 4 Also using a single group pretest-posttest design, Ajzenman et al. (2013) demonstrated that 12 weeks of hippotherapy increased postural stability, receptive communication, coping, self-care, low-demand leisure participation, and social interaction in children with autism. Together, these studies provide preliminary evidence that hippotherapy has the potential to increase the social functioning of children with autism. However, these studies are limited in that they use singlesubject or single-group designs and small sample sizes; furthermore, hippotherapy has not been compared to standard of care. Therefore, the effects of hippotherapy on social functioning of children with autism still need to be investigated using a rigorous experimental design providing a comparison to current standard of care. Our study aims to assess the effectiveness of hippotherapy focused on improving social functioning abilities for children with ASD in comparison to standard care. The social responsiveness scale (SRS) has been chosen as the primary outcome measure to evaluate social functioning abilities. Specifically, the scale consists of a 65-item questionnaire that assesses the severity of ASD (Constantino, 2002). This scale is comprised of five subscales: social awareness, social communication, social motivation, autistic mannerisms, and social cognition. The intended indication for this study is to establish the efficacy of hippotherapy in comparison to standard care to improve social functioning in children with ASD. This study is considered a phase III trial. The hippotherapy intervention involved in our study is based upon the intervention done by Ajzenman et al. (2013). To increase the rigor of empirical evidence in this field, this study will be a randomized controlled trial with a primary endpoint of establishing efficacy for hippotherapy for children with ASD and will utilize blinded assessors to evaluate primary outcomes. 5 Synopsis of Proposed Study Subject Identification: Patients will be included in the study based on the following criteria: children between the ages of 5-12; clinical diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD); were of full-term birth; have the ability to follow one-step directions and be able to ambulate independently with or without assistive devices. Patients will be excluded if they meet any of the following criteria: have severe behavioral issues that can result in self harm or harm to others and/or to animals; previous exposure to any equine therapy; and have a clinical diagnosis of severe sensory impairment, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and other neurological conditions. Study Treatments: “Hippotherapy is the incorporation of equine movement through physical therapy, occupational therapy, or speech language pathology professionals in treatment” as defined by the American Hippotherapy Association (AHA, 2010). The American Hippotherapy Association defines professionals in treatment as “professionals that use evidence-based practice and clinical reasoning for the purposeful manipulation of equine movement to engage the sensorimotor and neuromotor systems to create functional change in the patient” (AHA, 2010). Hippotherapy will be used as the form of treatment in the intervention group. The control group will receive standard occupational therapy care in order to compare the outcomes of both the experimental and control groups. Standard occupational therapy for children with ASD consists of any traditional outpatient, home health, and/or school-based services, where treatments are individualized based on the child's needs. 6 Study Measurements: The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) will be utilized to assess social functioning at pre/post-intervention for both treatment groups. This scale is a 65-item questionnaire that consists of five subscales as a means of measuring the severity of ASD symptoms (Bass et al. 2009). The five subscales consist of the following: social awareness, social cognition, social communication, social motivation, and autistic mannerisms. Total SRS scores consist of the summation of the five subscale scores. Patients’ total SRS scores will be calculated and used to assess the difference of social functioning between pre and post intervention for both hippotherapy and standard care. A reduction of the composite SRS score demonstrates an improvement in social functioning. Figure 1. Visit Table 7 Study Design Methods: This study is a 1:1 randomized controlled superiority trial with a less than hypothesis conducted with children ages 5-12 with ASD. Baseline evaluation will consist of a pre-intervention evaluation that will take place prior to the 12-week intervention by the child’s schoolteacher. A post-intervention evaluation will occur after the weekly therapy session at the end of the 12th week. Subjects will undergo either hippotherapy or standard care for 60-minute weekly sessions for a total of 12-weeks. The primary objective of this study is to establish effectiveness of hippotherapy for children with ASD. The primary endpoint will be the difference in social functioning skills between the intervention and control group; prespecified 8 secondary endpoints will be increases in social awareness, cognition, communication, motivation, and a decline in autistic mannerisms. Analysis plan: A two-sample t-test analysis will be utilized to test the difference between intervention group means of the composite SRS. Two-sample t-tests will also be utilized to assess the difference between treatment group means on each of the SRS subscales to include the following: social awareness, social cognition, social communication, social motivation, and autistic mannerisms (secondary endpoints). Variable significance will be assessed at an alpha level of 0.05. Inference and Sample size: The primary efficacy outcome measure is the composite score on the SRS. Based on current literature, we specified a minimal clinically relevant detectable reduction in social functioning deficits of 10 (difference between mean of 0 for control group and -10 for treatment group) (Bass et al. 2009). As prior research is limited in this area, to estimate pooled standard deviation for a 10-point reduction in social functioning deficits Cohen’s d effect size was used (Bass et al. 2009). Bass et al. (2009) reported an effect size of d= 0.66, Mpre= 85.9 and Mpost= 73.6, these values represent means of composite SRS scores pre and post 12-week hippotherapy intervention for the intervention group. Based on these values a pooled standard deviation of 18.64 was calculated. We selected a sample size of 56 patients per group for an overall sample size of 112 to have 80% power. Therefore we estimated a standard error of 3.52 (= sd*sqrt(2/56)) and a critical value and 95% confidence interval of -6.9 (-13.8, 0). The design will discriminate between the following 9 hypotheses: Ho: Θ ≥ 0; Halt: Θ ≤ -13.8. A sample size of 54 per treatment group would be needed to have 97.7% power to discriminate between hypotheses and a sample size of 37 per group is needed to have 90% power. Study Implementation and Conduct Recruitment: Subjects will be recruited from the Larimer County school system and the Larimer County ASD Center for Therapeutic Services based on a known diagnosis of ASD according to the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) autism spectrum diagnosis. Recruitment will be monitored by study personnel monthly and if recruitment slows, problem solving may include more rigorous recruiting for children with autism in Colorado school districts outside of Larimer County. Screening: All children referred to the study will be screened for enrollment by the principal investigator based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria previously discussed. After screening, parents will be required to consent to pre-testing, 12 weeks of hippotherapy and one post testing session prior to enrollment. Retention: Retention is not expected to be a significant concern with this study given that autism is considered a chronic condition and many children are not eligible to continue receiving therapeutic services reimbursed by insurance unless a significant change in condition can be justified. Therefore, parents are often required to pay expensive therapy costs out of pocket to ensure their children receive ongoing services. Parents in either group (hippotherapy or standard 10 of care) may see this study as an opportunity to receive ongoing therapeutic services without a financial burden and will be focused on completing the study whether their child is randomized to the hippotherapy group or the standard of care group. Since all children included in this study are of the age to attend public school, the study will be completed during the months school is in session, and the children’s primary teacher will be responsible for completing both pre and posttest assessments. Children randomized to both groups will also receive two free riding sessions once their post-test assessment has been completed and data has been received by study personnel. Non-compliance is not a major concern of the investigators in this study due to the reasons mentioned above. However, drop-in concerns are more likely to occur than drop-out as some parents in the standard of care group might be inclined to pay out of pocket for hippotherapy if they perceive this to be a more superior treatment than standard occupational therapy. The statistical power of the study will be decreased if subjects do not comply with the treatment protocol (either group). Therefore, parents will be educated during the consenting process on the importance of compliance to study allocation. Randomization: Children who complete the initial screening and pre-testing and are found to be eligible for this study will be randomized in a 1:1 fashion to either a treatment (hippotherapy) or control group (standard occupational therapy). A blinded statistician will utilize a computer generated block randomization scheme stratified based on the composite of the Social Responsiveness Scale by moderate deficits in social functioning (SRS ≥78) or mild deficits in social functioning (SRS < 78) to promote comparable groups and to allow for direct analysis of 11 the effects of treatment type on severity of disability. It’s expected the severity of disability will be a strong covariate in predicting overall outcome and stratification will reduce the chance for confounding in this study. Our analysis must account for stratification of this variable. We will randomize in blocks of 10 to ensure equal numbers of subjects in each group which should also increase power and limit confounding. The randomization code will be kept in a secure locked cabinet within the biostatistician’s office and no other study personnel will have access to this code. Please see attached appendix with randomization table for this trial. Blinding: This will be a single blind study with concealed allocation. Challenges with blinding will be a limitation in this study as it is with many rehabilitation trials, but efforts will be made to keep outcome assessors (teachers) blinded to group allocation. Standard of care occupational therapy will be completed in the clinic on-site of the equestrian center so travel for both groups will be similar and teachers will not be exposed to different travel arrangements. Parents and children will be asked not to discuss any aspect of their therapy with their teachers, but there is no way to ensure this does not occur. Missing Data: The principal investigator will be responsible for obtaining completed pre and post-test assessments from the blinded assessors within 7 days of completion. She will review each assessment for completion and notify the blinded assessor immediately of any data that has not been completed. Study personnel will focus on maintaining study quality control to eliminate the potential for missing data. However, the recruited sample size will be 10% greater than the calculated sample size (64 subjects) to account for the possibility of 10% attrition. All statistical analysis will be completed based on an intention to treat analysis to manage missing 12 data. Data will be monitored frequently for missing data which will be corrected as soon as possible. All subjects (both groups) will be offered two free riding sessions after post-test assessments have been completed to minimize loss of data. 13 References Ajzenman, H. F., Standeven, J. W., & Shurtleff, T. L. (2013). Effect of Hippotherapy on Motor Control, Adaptive Behaviors, and Participation in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67(6), 653-663. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2013.008383 American Hippotherapy Association. (2010). Hippotherapy as a Treatment Strategy. Retrieved 1/9/2014, 2014, from http://www.americanhippotherapyassociation.org/hippotherapy/hippotherapy-as-atreatment-strategy/ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 Sites, United States, 2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Charman, T., Swettenham, J., Baron-Cohen, S., Cox, A., Baird, G., & Drew, A. (1997). Infants with autism: an investigation of empathy, pretend play, joint attention, and imitation. Developmental psychology, 33(5), 781. Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2002). The social responsiveness scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. Dawson, G., & Osterling, J. (1997). Early intervention in autism. The effectiveness of early intervention, 307-326. 14 Dawson, G., Toth, K., Abbott, R., Osterling, J., Munson, J., Estes, A., & Liaw, J. (2004). Early social attention impairments in autism: social orienting, joint attention, and attention to distress. Developmental psychology, 40(2), 271. Karanth, P., & Chandhok, T. S. (2013). Impact of early intervention on children with autism spectrum disorders as measured by inclusion and retention in mainstream schools. Indian Journal Of Pediatrics, 80(11), 911-919. doi: 10.1007/s12098-013-1014-y Klintwall, L., Eldevik, S., & Eikeseth, S. (2013). Narrowing the gap: Effects of intervention on developmental trajectories in autism. Autism: The International Journal Of Research And Practice. McGee, G., Feldman, R., & Morrier, M. (1997). Benchmarks of Social Treatment for Children with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord, 27(4), 353-364. doi: 10.1023/A:1025849220209 Orsmond, G. I., Shattuck, P. T., Cooper, B. P., Sterzing, P. R., & Anderson, K. A. (2013). Social Participation Among Young Adults with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord, 43(11), 2710. Tabares, C., Vicente, F., Sanchez, S., Aparicio, A., Alejo, S., & Cubero, J. (2012). Quantification of hormonal changes by effects of hippotherapy in the autistic population. Neurochemical Journal, 6(4), 311-316. doi: 10.1134/s1819712412040125 Taylor, R. R., Kielhofner, G., Smith, C., Butler, S., Cahill, S. M., Ciukaj, M. D., & Gehman, M. (2009). Volitional change in children with autism: A single-case design study of the impact of hippotherapy on motivation. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 25(2), 192-200. 15 Thomas, K. C., Morrissey, J. P., & McLaurin, C. (2007). Use of autism-related services by families and children. J Autism Dev Disord, 37(5), 818-829. Wood, W., McDaniel, C., & Hoesly, B. (2015). A 35-year systematic mapping review study of refereed literature on equine assisted activities and therapies. (Unpublished manuscript). Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Colorado State, Fort Collins, Colorado.