A Day in the Life Mapping Project Andrea Twiss

advertisement

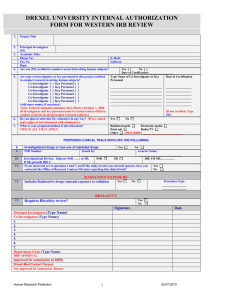

A Day in the Life Mapping Project Andrea Twiss-Brooks, University of Chicago, atbrooks@uchicago.edu (principal investigator) Kathryn Carpenter, University of Illinois-Chicago, khc@uic.edu (co-investigator) Christine Frank, Rush University, christine_frank@rush.edu (co-investigator) Gail Hendler, Loyola University of Chicago, ghendler@luc.edu (co-investigator) Connie Poole, Southern Illinois University, cpoole@siumed.edu (co-investigator) Natalie Reed, Midwestern University nreedx@midwestern.edu (co-investigator) Nancy Fried Foster, Ithaka S+R nancy.foster@ithaka.org (consultant) Building on the results of a previous project from which we gained an understanding of ethnographic methods used at the University of Rochester Libraries and considered their applicability to health sciences libraries, we developed a low-cost, six-institution study focused on how third-year medical students seek and use information in the course of daily activities, especially activities conducted in a clinical setting. Third-year students typically rotate through different clinical specialties and types of clinics, exploring their practice options and beginning the process of selecting the post-doctoral specialty. For many, this is the first time they may be on their own for finding answers to real clinical questions. The study allowed us to learn about how they discover evidence that supports their clinical education and to learn what promotes discovery of resources and conversely, what barriers exist that hinder discovery or use. Participants at each institution were asked to mark their movements on a map for one full day in which at least part of their time was spent in a clinical setting. On the day following the mapping day, we interviewed each student, asking him or her to narrate the day, paying special attention to those times when information was sought or used. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Interview transcripts are in the process of being analyzed to develop a picture of what third-year medical students need to do in order to find and use information when they are in a clinical setting. The study was supported in part by a technology outreach subcontract award from the Greater Midwest Region of the National Network of Libraries of Medicine (GMR-NNLM) and in part by each institution providing in-kind contributions (gift cards as incentives) and staff to perform interviews and transcript analysis. Project findings will provide insight for future review on how and how well the library is meeting the current needs of these fledging practitioners and what additional resources and services are needed to support a clinician’s health practice. The findings will also help participating institutions identify emerging needs that the library has not traditionally met but that would fall within its bailiwick. Objectives: i. To understand how fledgling clinicians find answers to clinical questions and if those answers enhance and support their clinical decision-making. a. When do they seek information related to their education and clinical experience? b. What devices do they use to seek information related to their education and clinical experience? c. Where are they when they seek information related to their education and clinical experience ii. To understand the role of the library and other information sources in meeting these information needs. iii. To test this particular ethnographic method to see if it is a viable tool for adding to the body of library evidence-based practice, and therefore applicable for use elsewhere. Lessons learned about the process: i. Get support from the medical school administration ii. Incentives were important in recruiting participants iii. Working with institutional review boards and offices of sponsored research always took longer than anticipated iv. A project leader with time and energy to devote tothe project was critical v. Services of a professional consultant were extremely helpful vi. Use a variety of approaches for project team communication Preliminary results: The glimpse into a day in the life of sixty-nine third year medical students provided us an opportunity to see how information discovery, retrieval and use takes place in a fast-paced environment. While the participants demonstrated knowledge of authoritative and in-depth resources for medical information, they most often need a quick, factual answer retrieved in a minute or less in a hectic clinical setting. This would often lead to the use of Google or Wikipedia on a smartphone as a first choice. A medically oriented app optimized for mobile devices was commonly a next step. And finally, when more time allowed, usually away from the exam room and patients, the participants would return to conditions, medications, diagnoses, and treatments that had piqued their interest earlier in the day for further exploration in more academic and authoritative resources like PubMed or UptoDate. Third year medical students also spend a good deal of their time viewing and contributing to (writing up notes on patient visits) the electronic health records of the patients they see in clinical settings. Factors leading to selection of particular information tools include speed, convenience, lack of need to login, recommendations by trusted authorities (library, residents, attending physicians), availability on a particular device, organization and presentation of the information in a useful way, and more. The most commonly occurring barrier to use of information was lack of wireless or mobile phone network coverage in some clinical settings. Time management was a theme that occurred over and over. When students were not engaged with patients or doing other clinical tasks, they were very seldom idle. Studying for regularly scheduled exams (called “shelf exams”) occupied a lot of their down time between patients, time during their commutes on public transit, and their time at home after their clinical shifts were complete. Some of the participants who were commuting by car would use that time to listen to podcasts on medical topics or phone their parents, other relatives or friends. Print books were mentioned often, and we found that a little surprising for this born digital population. Images and videos are an important part of the arsenal of learning resources they employ. YouTube videos of surgeries were mentioned quite a bit by the students on surgical rotations.