Intercultural Conflict Case Analysis

advertisement

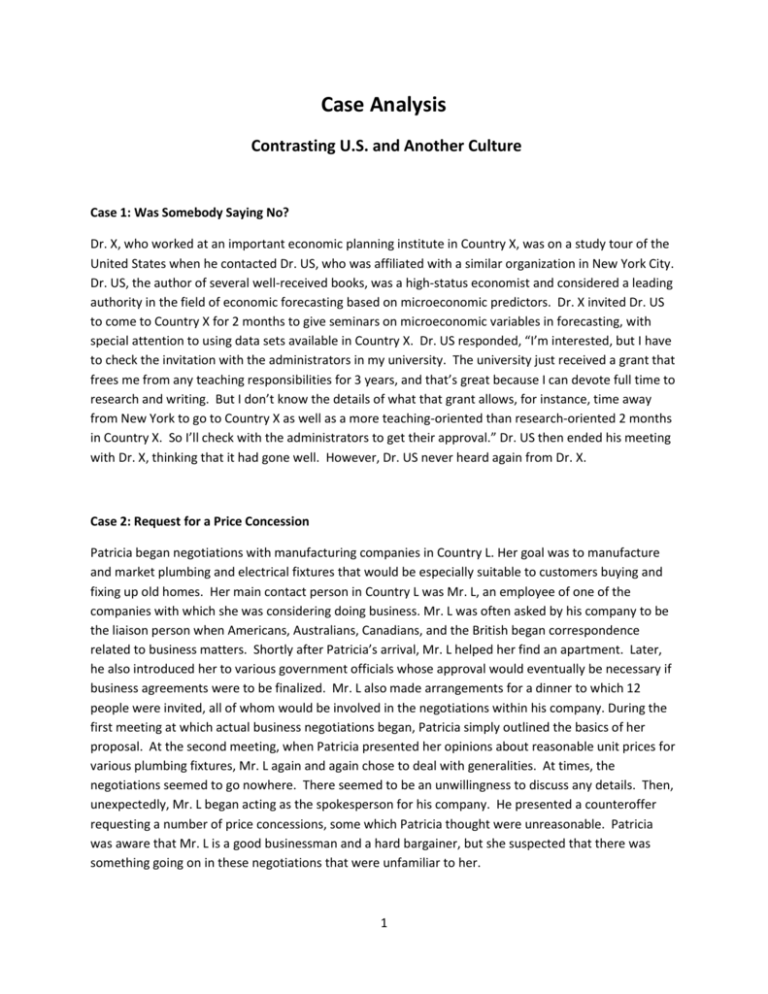

Case Analysis Contrasting U.S. and Another Culture Case 1: Was Somebody Saying No? Dr. X, who worked at an important economic planning institute in Country X, was on a study tour of the United States when he contacted Dr. US, who was affiliated with a similar organization in New York City. Dr. US, the author of several well-received books, was a high-status economist and considered a leading authority in the field of economic forecasting based on microeconomic predictors. Dr. X invited Dr. US to come to Country X for 2 months to give seminars on microeconomic variables in forecasting, with special attention to using data sets available in Country X. Dr. US responded, “I’m interested, but I have to check the invitation with the administrators in my university. The university just received a grant that frees me from any teaching responsibilities for 3 years, and that’s great because I can devote full time to research and writing. But I don’t know the details of what that grant allows, for instance, time away from New York to go to Country X as well as a more teaching-oriented than research-oriented 2 months in Country X. So I’ll check with the administrators to get their approval.” Dr. US then ended his meeting with Dr. X, thinking that it had gone well. However, Dr. US never heard again from Dr. X. Case 2: Request for a Price Concession Patricia began negotiations with manufacturing companies in Country L. Her goal was to manufacture and market plumbing and electrical fixtures that would be especially suitable to customers buying and fixing up old homes. Her main contact person in Country L was Mr. L, an employee of one of the companies with which she was considering doing business. Mr. L was often asked by his company to be the liaison person when Americans, Australians, Canadians, and the British began correspondence related to business matters. Shortly after Patricia’s arrival, Mr. L helped her find an apartment. Later, he also introduced her to various government officials whose approval would eventually be necessary if business agreements were to be finalized. Mr. L also made arrangements for a dinner to which 12 people were invited, all of whom would be involved in the negotiations within his company. During the first meeting at which actual business negotiations began, Patricia simply outlined the basics of her proposal. At the second meeting, when Patricia presented her opinions about reasonable unit prices for various plumbing fixtures, Mr. L again and again chose to deal with generalities. At times, the negotiations seemed to go nowhere. There seemed to be an unwillingness to discuss any details. Then, unexpectedly, Mr. L began acting as the spokesperson for his company. He presented a counteroffer requesting a number of price concessions, some which Patricia thought were unreasonable. Patricia was aware that Mr. L is a good businessman and a hard bargainer, but she suspected that there was something going on in these negotiations that were unfamiliar to her. 1 Case 3: The Quiet Participant Ms. W had recently been promoted to a position of authority and was asked to represent her company and Country W’s needs at the head office in Montana, U.S. Her relationships with fellow workers seemed cordial but rather formal from her perspective. She was invited to attend many policy and planning sessions with other company officials, where she often sat rather quietly as others generated ideas and engaged in conversation. The time finally came when the direction of the company was to take in Country W was to be discussed. A meeting was called to which Ms. W was invited. As the meeting was drawing to a close after almost 2 hours of discussion, Ms. W, almost apologetically, offered a suggestion-her first contribution to any meeting. Almost immediately, a local vice president said, “Why did you wait so long to contribute? We needed your comments all along.” Ms. W felt that was a harsh comment. Case 4: In The Matter of Mr. K Mary is an expatriate staff member in an international organization in Country K. Mary is being asked to take sides in an office dispute. A few weeks ago a vacancy occurred in the department where Mary works. The two candidates for the position, both college graduates, were an older man (Mr. K) who has been working in the field for 15 years and a younger man with more up-to-date technical credentials, a superior educational background, and two years of experience in the organization. From a technical standpoint, the younger man was a much stronger candidate and also a more creative person, and he was in fact selected for the position by the chair of the department who is an expatriate. Mr. K and many of his and Mary’s colleagues were stunned by the decision, seeing it as a denial of his years of experience and dedication to the organization. Mr. K is extremely embarrassed at being passed over and has not appeared in the office since the announcement was made. Now his colleagues are circulating a petition to the chairperson to reconsider his decision and put Mr. K into the job he deserves. They have asked Mary to sign the petition, already signed by all of them, and to participate actively in this campaign. Mary in fact feels the right choice was made and is reluctant to get involved, but she is under increasing pressure to “do the right thing.” She is asking for your advice. 2 Case 5: Considering the Source Susan is the technical expert at a provincial agricultural extension office in Country Y. A delegation from the Minister’s office is coming next week to discuss an important change in policy. Susan is the person who can make the most substantive contribution to this discussion, but she is not being invited to the meeting. Instead, her boss, Mr. Y, has been picking her brain for days and has asked her to write a report for him containing all the important points he should make. Finally, Susan asks Mr. Y why he doesn’t just bring her along to the meeting and let her speak directly to the delegation. He says she is too young to be taken seriously, and besides, she is a woman. Her arguments are too important, he says, and he doesn’t want them to be discounted because of their source. Case 6: The Sick Secretary Tom works for a U.S. company in Country K. Sometimes he wonders why he ever accepted a position overseas—there seems to be so much that he just doesn’t understand. One incident in particular occurred the previous Friday when his secretary, Ms. K, made a mistake and forgot to type a letter. Tom considered this a small error, but made sure to mention it when he saw her during lunch in the company cafeteria. Ever since then, Ms. K has been acting a bit strange and distant. When she walks out of his office, she closes the door more loudly than usual. She will not even look him in the eye, and she has been acting very moody. She even took a few days of sick leave, which she has not done in many years. Tom has no idea how to understand her behavior. Perhaps she really ill or feels a bit overworked. When Ms. K returns to work the following Wednesday, Tom calls her into his office. “Is there a problem?” he asks. “Because if there is, we need to talk about it.” It’s affecting your performance. Is something wrong? Why don’t you tell me, it’s okay.” At this point, Ms. K looks quite distressed. She admits the problem has something to do with her mistake the previous Friday, and Tom explains that was no big deal. “Forget it,” he says, feeling satisfied with himself for working this out. “In the future, just make sure to tell me if something is wrong.” But over the next few weeks, Ms. K takes 6 more sick days and does not speak to Tom once. 3 Case 7: Business or Pleasure? Tim, the top salesperson in a Midwestern U.S. area, was asked to head up a presentation of his office equipment firm to a company in Country H. He had set up an appointment for the day he arrived, and even began explaining some of his objectives to the marketing representative who was sent to meet his plane. However, it seemed that the representative, Mr. H, was always changing the subject; Mr. H persisted in asking a lot of personal questions about Tim, his family, and his interests. Tim was later informed that the meeting had been arranged for several days later, and his hosts hoped that he would be able to relax a little first and recover from his journey, perhaps see some sights and enjoy the country’s hospitality. Tim responded by saying that he was quite fit and prepared to give a presentation that day, if possible. Mr. H. seemed a little taken aback at this, but said he would discuss it with his superiors. Eventually they agreed to meet with Tim, but at the subsequent meeting, after a bit of chat and some preliminaries, they suggested that he might be tired they could continue the next day after he had some time to recover. During the next few days, Tim noticed that though they had said they wanted to discuss details of his presentation, they seemed to spend an inordinate amount of time on inconsequential activities. This began to annoy Tim, as he thought that the deal could have been closed several days ago. He just did not know what they were driving at. Case 8: The Tea Party John, manager of a supermarket chain based in Milwaukee, U.S., was eager to establish trade ties with Country K. Through a middleman, Mr. K, John reached an agreement to import 2,400 packages of tea from Country K. The shipment came in just in time for the Thanksgiving Day sales peak. John, a tea lover himself, was impressed by the quality of the tea, and the packaging was better than he had expected. He anticipated good sales of the tea in his stores. However, because of the small size of the transaction, the transportation cost per unit was quite high. In order to profit from this transaction, John decided to price the tea imported from Country K a little higher than the domestic brands they have been selling. Mr. K disagreed, suggesting that John cut the price to match other brands first. Mr. K argued that once the imported brand was established and recognized by the consumers, both sides could profit from selling a larger amount at a lower cost per unit. John, however, was unwilling to start out selling at a loss. Three weeks later Mr. K called John and learned that the tea had not sold well and again suggested that John try to lowering the price, but John seemed to have lost interest in the deal. 4