House of Lords Class Essay

advertisement

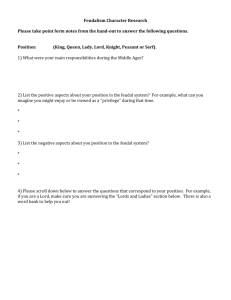

Year 13 – Parliamentary Reform Focus – The House of Lords – where to now? Class essay – written together via a debate. Arguments taken from three angles: Fully elected? Fully appointed? A mixture of both? There are many arguments to support the idea of a fully elected House of Lords. Since the Labour Reforms of 1998, the HOL has removed all but 92 hereditary peers and replaced them with appointed peers. The reforms appear to have stalled since then and there appears to be no consensus on the way forward. Some of the major criticism of the House of Lords include that it is corrupt and packed full of party supporters, it is undemocratic and unaccountable. It is full of old people some of are too sick to attend or to carry out their duties e.g. Baroness Thatcher in her latter years. It is also far too big, particularly as it is the ‘second chamber’ or ‘revising chamber’. We would like to propose that a fully elected HOL is the best way forward for the following reasons: A fully elected chamber would certainly give the Lords a mandate for initiating and amending legislation. As this is one of the main functions of the Lords at present, it would certainly silence any critics who feel that they currently have no right to be doing this. As they are not elected they are criticised for being out of touch and unrepresentative. Therefore the only way to address this democratic deficit is to have a fully elected chamber instead. This is certainly the preferred option for the Liberal Democrats. Secondly, if the Lords was fully elected there would better representation and a more diverse range of members. If we consider the models of representation, we could further develop this by arguing that the Lords could perhaps become more of a mirror representation of the UK population, rather than the trustee model that we have in the House of Commons. In that way the House of Lords would have a very different identity to the Commons and this would silence the critics who believe that a fully elected Lords would simple serve to undermine the Commons. Furthermore, if we wanted to ensure a more representative second chamber (HOL) then a different voting system could be used to ensure that we achieved a more representative outcome with more women and minorities in place. This could not be guaranteed of course, but it may be more likely to occur under PR and devolution has shown this to be true over the last few years. Certainly the devolved areas of the UK show a greater percentage of women and minorities than the Westminster parliament does. Thirdly, we believe that the expertise of the Lords would not necessarily be lost if the Lords was elected as it is highly possible that many of the current peers would be happy enough to run for election, and would be likely to retain their seats as the voters would be reassured that they know what they are doing. Fourthly and perhaps most importantly, the House of Lords would finally be accountable to the people and this would arguably make sure that the people in it perform the functions of the second chamber more effectively. Last, but not least, the House of Lords really does personify the traditional element of our constitution and in many ways makes the political structure of the UK appear out of date. Whilst the traditions and customs of Westminster have a certain charm of their own, they have no place in a modern democracy and it is time for the UK to move on and address the glaring democratic deficit that it so clearly accepts. To argue that ‘this is just the way it is’ seems to be defeatist and unambitious and cannot be justified in this day and age. Another option for the House of Lords would be to abandon all further reform and, after the death of the remaining hereditary peers, keep the chamber fully appointed. The main arguments to support this is that the HOL is presently very distinct from the House of Commons and it would be best to keep it this way. There is also a high degree of voter apathy as it is and surely more elections would just exacerbate this problem, in 2011, only 35% turned out for the AV referendum. Should we push ahead and hold elections to the Lords anyway? Some would argue that to ignore public opinion wold be costly and unnecessary, therefore we say that there is no call for an elected HOL. Secondly, as we have an uncodified constitution, a newly elected chamber would need to be codified and this would also be an unnecessary upheaval and then the arguments would begin over the monarchy and whether that should also be abolished. On another related and more positive note, the HOL symbolises the traditional element of the British Constitution and is what makes our constitution unique and strong………it provides continuity and stability and to reorganise and abolish the HOL and possibly the monarchy when there is no need to appears to be a change for changes sake. Importantly, in terms of functions and performance the HOL is possibly more effective than it has ever been. The older average of the Lords is reassuring, not a negative, and ¼ of members are female. In terms of oversight and scrutiny of legislation, the HOL is an extremely busy and effective chamber and the level of expertise in there has made it a robust and vital, the amendments to the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005, being just one example of this. Since the formation of the Coalition government since 2010, and the weakness of the Labour party in opposition, the Lords have been even more robust in opposing the government. Furthermore, the debating function of the Lords offers a good contrast to the Commons as it is more informed and less adversarial. The votes are less whipped and the members are able to be more independent in their scrutiny, this is demonstrated by the large amount of cross benchers. Perhaps the most effective option for Lords reform would be a mixture of both elected and appointed. That way, the legislature would provide the best of both expertise and representation. There would be enough party loyalty to keep some form of ideological direction and yet they would have a greater mandate as they would be representative in part and therefore more democratic. It would not be a good idea, to have it fully elected because then it would be too political, too similar to the Commons, there would be too much ping pong and maybe even gridlock. The loss of expertise would mean that the bills would not be polished enough. In the same way, it would not be a good idea to have it fully appointed as the public would still have no say and therefore it would not be viewed positively. As it stands, the most significant development in the House of Lords over the last 15 years has been reform, other achievements are less visible. Although there are many that would argue with this – using the examples of robust scrutiny that has taken place over the last few years. In conclusion, it is easy to argue that at half elected and half appointed HOL would be the easiest way to get consensus. This has been demonstrated by the fact that there has been no significant change since 1997. The performance of the House of Lords is good, committee work is excellent and there is a high level of legislative scrutiny. It is accountability that is the problem, and a half elected solution would only half solve this problem. If a compromise like this is pursued as the best option, there is a distinct possibility that there would be even more problems. If there were two types of peers, there might be rivalry and that might cause even more problems. There is also the issue of cost as peers at present only qualify for an allowance and not a salary. The Lords spiritual is another area of potential conflict if the House of Lords is to see further reform because this will ultimately become a constitutional issue as to remove them would be effectively saying that the UK should become secular, and a whole new debate would be started. Did Tony Blair start something that cannot be finished? The question for the UK remains, can we carry on with a less than ideal but very effective parliamentary democracy, or do we restructure, re-evaluate and reform our parliament once and for all? The question remains at the forefront of political debate, but in the background of public interest and without support or consensus nothing is likely to change in the near future, whether is justified or not. Year 13 2015 Contributers: Jonas Rasche Corey Norwood Alex Best Andrew Abdi Ross Wardlow Nikolai Koplewski