aaronsonessay1

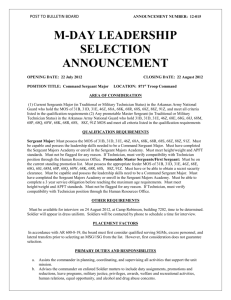

advertisement

Zachary Aaronson The Rising of the Moon “The Rising of the Moon,” written by Lady Gregory, debuted at the Abbey Theatre in 1907. The theater was founded by Gregory and her fellow Irish playwrights, W.B. Yeats and J.M. Synge . “The Rising of the Moon” is a wonderful play. It is pithy, yet densely packed with wisdom and substance. The play serves as an astute reflection of the socioeconomic struggles of the Irish in the early 20th century. Gregory addresses topics such as Irish-British relations, the use of disguise and finding the inner self. The protagonist is the Sergeant and his transformation and realization of his past youth desires upon meeting “The Man” is “The Rising of the Moon’s” most important aspect. The play begins with three Irish policemen entering. They are currently hunting for a escaped prisoner in hopes of catching him before he flees the country. The Sergeant, oldest of the three, decides to stay near the ocean because he believes the fleeing convict will contact friends to smuggle him by boat to his freedom. After the other two officers search elsewhere for the prisoner, an unnamed man approaches the Sergeant. This man has disguised himself because he is the political prisoner that the policemen are searching for. The man, who later identifies himself as “Jimmy Walsh, a ballad singer,” is the character who sets up the dilemma that the Sergeant needs to determine by the end of the play (Gregory 51). As the Sergeant and the man converse, smoking cigarettes, the Sergeant begins trying to put himself in the position of the escaped convict. The Sergeant is moved by the Man’s song, “The Rising of the Moon.” The play takes its name from this old Irish ballad the Man is singing. The ballad recalls a battle that took place between the Irish and British, clearly suggesting that there remains a difference between the Sergeant and the Man. The play is intended to be staged with the Sergeant being British and the Man being Irish. The Sergeant is reminded of his youth, when he too was once a young revolutionary (Lady Gregory). He recalls the passion he felt in his heart, fighting political causes against those who held power. When the two other officers return, the Sergeant is put in a position where he could arrest the convict and receive his bounty of one hundred pounds. However, because of his conversation with the disguised prisoner, the Sergeant decides not reveal to him to the other officers. The other two policemen exit, leaving the Man and the newly enlightened Sergeant together onstage. The Man leaves the Sergeant with parting words that echo the call of the Irish revolution. The Sergeant, alone on the stage, exclaims, “A hundred pounds reward! A hundred pounds! I wonder, now, am I as great a fool as I think I am” (Gregory 57). Immediately, there is an embrace of Gregory’s dialogue and stage direction. The stage direction is minimal, only indicating that the stage be moonlit and takes place on the “side of a quay in a seaport town” (Gregory 50). The only other significant direction is that the Sergeant is the superior of the other two policemen, though that can just be inferred by his visible dominance over them. Since the play takes place in only one setting, its format is basic. Props, however, are of great interest to Gregory. The props in this play ultimately emphasize the character development. The first indicated is the hat and wig, which serve as the Man’s disguise. The second prop. The barrel itself is woven into the narrative, as the Sergeant reflects upon the possibility that he too could have been a criminal. Gregory intends for the reader to see the development of the Sergeant as he garners empathy for the same prisoner he is tracking. The Sergeant says to the Man, “If it wasn’t for the sense I have, and for my wife and family, and for me joining the force the time I did, it might be myself now would after breaking gaol and hiding in the dark, and it might be him that’s hiding in the dark and that got out of gaol would be sitting up here where I am on this barrel” (Gregory 55). This is one of the more significant lines throughout the play. It is the moment where the Sergeant thinks about the circumstances that put him as a figure of the law, consequently freeing him from a life of crime. He recalls that if it were not for his family and job, he too could have been a fugitive criminal. This empathetic thought demonstrated by the Sergeant suggests a change in his attitude. In the beginning when the Sergeant was onstage with the two policemen he says to them, “Well, we have to do our duty in the force. Haven’t we the whole country depending on us to keep law and order? It’s those that are down would be up and those that are up would be down, if it wasn’t for us” (Gregory 51). This exemplifies the Sergeant’s narrow minded view of the world. By saying this, he makes the distinct assumption that criminals are criminals for the sake of being criminals. It is a statement that is not at all understanding of how the criminal was put into a position where he would need to commit a crime. Crime, the Sergeant . Therefore, when the Sergeant is thinking about how easily he himself could have lived the life of a fugitive, he is exhibiting a sympathetic and understanding attitude differing from his views in the beginning of the play. The Rising of the Moon is a work intended by Gregory to sympathize with the socialist cause. Not only does “The Rising of the Moon” serve to reiterate the Man’s position as an escaped political prisoner, it reflects the socialist beliefs of Gregory. The Man’s parting words with the Sergeant have revolutionary undertones, “Well, good-night, comrade, and thank you. You did me a good turn to-night, and I’m obliged to you. Maybe I’ll be able to do as much for you when the small rise up and the big fall down…when we all change places at the rising of the Moon” (Gregory 57). The Man refers to the Sergeant as his “comrade,” a word often associated with socialist rhetoric. The Man’s comment “when the small rise up and the big fall down” suggests the inevitable revolution Socialists claims will take place when the proletariats (workers) would overthrow the bourgeoisie (owners). It is through the disguised man that the Sergeant is able to reveal his true self, the self of his youth. The Man says to the Sergeant, “Sergeant, I am thinking it was with the people you were, and not with the law you were, when you were a young man” (Gregory 55). The Sergeant’s true identity, like the man, was disguised. Instead of a wig and beard to disguise himself, however, he had hidden his inner self behind the law. He no longer exhibited his youthful ambitions, which before his change of heart he referred to as being, “foolish then, that time’s gone” (Gregory 55). Eventually as they converse, the Sergeant reveals his true self; he is free from the constraints of being a representative of the law. The Sergeant is able to embrace this newfound sense of compassion and thanks the Man for enlightening him. He says, “It’s a pity! It’s a pity! You deceived me! You deceived me well” (Gregory 56). Through calling the Man’s deception “well,” the Sergeant is already hinting that the conversation had changed him. That is why when the cops show up, the Sergeant does not reveal the Man as the escaped prisoner. This elaborate change in attitude can be contrasted with the beginning of the Man and the Sergeant’s conversation. Before he found out the Man’s true identity he states, “Don’t talk to me like that. I have my duties and I know them” (Gregory 55). Yet by the conclusion of the play, the Sergeant is complicit with the Man by hiding his hat and wig from the officers. It is clearly seen that his duties toward serving the law are no longer important to him. The act of the Sergeant handing the wig back to the Man is also intended to suggest the Sergeant’s fundamental change. The Sergeant, by giving back the disguise, is physically giving the means for the Man to continue to be free. His freedom thus allows him to continue rebelling against others. Therefore, the disguise acts as a symbol of the Man’s ability to rebel. Gregory is clever in that it took the Man’s disguise to “unmask” the Sergeant’s true beliefs. “The Rising of the Moon” is a marvelous example of Irish theater. It is a simple one act play, yet with so much depth and significance found throughout it. The action begins immediately, setting up a contrast between the law protecting Sergeant and the politically inclined free spirit demonstrated by the Man. Gregory use of character development is arguably her greatest accomplishment. Even more significant is how this character development takes place. The Sergeant’s change of heart is reflected as being a direct result of the Man’s deception through the use of his disguise. The disguise itself serves as a representation of the revolution, whose roots seem bound to Gregory’s socialist ideals. Symbolically, the act of the Sergeant returning the disguise to the Man maintains that the Sergeant is now sympathetic to the cause. “The Rising of the Moon’s” message remains clear as this text is an excellent reflection of the conflict between the British and Irish, attempting to apply a neutralist stance through the embrace of sympathy and understanding of fellow men. Works Cited Gregory, Lady. “The Rising of the Moon.” New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc, 2009. “Lady Gregory.” Theatre Database 27 Feb 2011. http://www.theatredatabase.com/20th_century/lady_gregory_001.html