Clearly is essential that undergraduate and postgraduate medical

advertisement

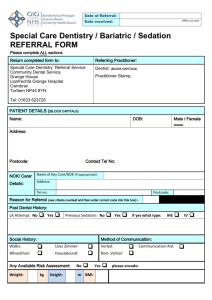

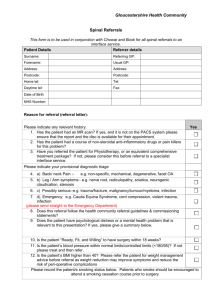

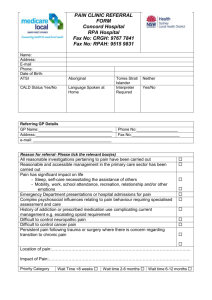

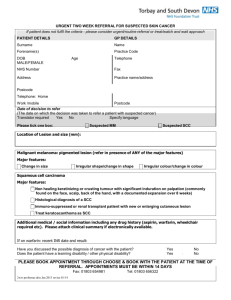

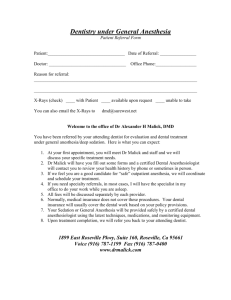

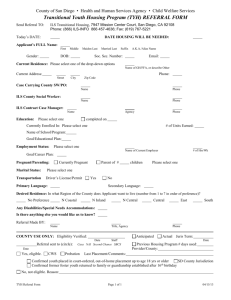

Guidelines for the referral of suspected oral cancer patients Introduction Worldwide, oral cancer has one of the lowest survival rates and remains unaffected despite recent therapeutic advances. [1] Early diagnosis and referral is a cornerstone to improve survival and to reduce diagnostic delay.[2] Unfortunately, almost one half of the oral cancers are diagnosed at advanced stages (III or IV), with 5-year survival rates ranging from 20% to 50% depending on tumors site.[3] However, several authors have identified insufficient educational preparedness of medical and dental professionals to reduce the burden of oral cancer through effective cancer control strategies such as reducing tobacco consumption, suggesting healthier diet and lifestyles and, particularly, performing early detection through screening examinations and appropriate follow-up. [4] The introduction of guidelines for the referral of suspected cancer is an important step towards primary care practitioners identifying patients with oral malignancy. Importance of Referral for Oral, Head and Neck cancers Delays in referral of suspected oral cancer cases for treatment caused by the clinicians have been identified by several reports. Thus, the design of a simple, clear, fail-safe referral scheme may greatly diminish the length of the delay.[5] The ability of the examiners to make a correct positive detection of oral cancer (sensitivity, Sn) shows a broad range worldwide: reported Sn scores varied from 0.4 to 0.9. [6] The specificity (Sp) ranged to 0.3 to 0.92, [6] low values scores for the screening of oral cancer would mean that patients with oral cancer may not be adequately referred for the decisive diagnosis and treatment. The use of the clinical guideline for referral of patients seems to significantly increase the diagnostic specificity for oral cancer and also to reduce the possibility of not referring an oral cancer case, and thus increasing the diagnostic delay. This phenomenon has also been described when the use of referral guidelines was studied in primary care settings. An audit of this initiative revealed a high proportion of non-malignancies were referred via the fast track system to the hospitals due to low sensitivity of visual detector guidelines. [7] Moreover, a worrying ignorance on oral changes associated to early forms of oral cancer (early diagnosis secondary prevention) particularly about leucoplastic, erythroplastic or leucoerythroplastic lesions amongst medical and dental professionals. [8] The implementation of clinical guidelines for dental professionals aimed at reinforcing these topics may increase diagnostic sensitivity and specificity when dealing with lesions suspicious for oral cancer. The clinical practice guideline for referral of oral cancer suspicious lesions has been elaborated by a panel of experts synthesizing the best available scientific evidence. The objective of the implementation of clinical practice guideline is to increase knowledge, to change behaviors and attitudes in clinical practice and to improve the quality of the clinical care.[9-10] 1 REFERRAL GUIDELINES AND PROCESS Clearly is essential that undergraduate and postgraduate medical and dental education should include the characteristics of a good referral guide in order to improve standards. Therefore, it is important that all members of the primary healthcare team are aware of oral cancer, of the importance of encouraging regular dental attendance, and of their role in the identification and appropriate referral of individuals with oral mucosal complaints which last longer than three weeks (Table 1). Table 1. Warning feature suggestive of oral cancers Red lesions Extraction socket not healing A lump Induration beneath a lesion, i.e. a firm infiltration beneath the mucosa Granular appearance Ulcer with fissuring or raised exophytic Fixation of lesion deeper tissues or to margins overlying skin or mucosa Abnormal blood vessels supplying a lump Voice change Pain or numbness Lymph node enlargement Loose tooth Weight loss The Rapid Access Route General medical and dental practitioners are encouraged to refer patient with a high index of suspicious cancer as a matter of urgency using the 2 week wait referral proforma (Appendix )الملحق هو استمارة اإلاحال. A High Index of Suspicion of cancer (urgent) - Ulceration of tongue / oral mucosa > 3 - Oral / Facial swelling > 3wks - Red or & white patch of oral mucosa - Unexpected tooth mobility not associated with periodontal disease - Un-resolving neck / salivary / thyroid mass >3 wks - Orbital mass - Neuropathy of cranial nerve - Hoarseness > 6 wks - Dysphagia > 3wks - Persistent sore throat General practitioners should be encouraged to: - Make referrals using the appropriate referral pro-forma for patients in whom there is a high index suspicion cancer as defined above. - Take the history of smoking and alcohol consumption. - Provide information on all current medication. - Observe the results of all recent investigations as Scan, FBS, LFTs and U&Es results 2 Quality in Referral Letters Sent for Maxillofacial centers Members of the primary dental health team must ensure they are aware of the local referral arrangements for oral cancer. It is best to establish these referral pathways before a patient with a suspicious oral lesion is seen in the dental practice (Table 2). Information required in referral letters for suspected malignancy: A) Administrative Data include: Marked as urgent Patient’s name Patient’s address Patient’s tel. no. Patient’s date of birth Patient’s gender Previous visited hospital Referrer’s name Referrer’s address Referrer’s tel. no. Clinical Data include: Description of site Diagram of lesion Size of lesion Shape of lesion Duration of lesion Symptoms Clinical appearance Risk factors Medical history If a referral is to be made, telephone contact should be made followed-up with a formal letter of referral. The referral letter should be marked ‘URGENT’ and addressed personally to a named consultant, and must include the details shown in table 2. The referring dentist should be aware of the likely scenario when the patient first attends the specialist unit. The patient may be advised to expect a biopsy (usually under local anaesthetic with or without sutures being placed) and that this is the only way to definitively diagnose the lesion. Clinical photographs are usually taken for the case notes as a matter of routine. Radiographical assessment of the head and neck may be performed, and blood may also be taken for analysis. It is important to realize that following referral the primary dental health teams have a continuing role. If oral cancer is diagnosed, the patient’s life is never going to be the same again. The dental practice should have an ‘open door’ policy and patients should be encouraged to return for further discussion and support as they feel they need. A formal follow-up appointment is a good way to show that they are not being abandoned into hospital care, without any support mechanism in place. 3 Table 2 Information required in URGENT Referral letter General Dental Practice: Date: Oral Cancer Specialist Unit: Dear Named Specialist: Re: Patient’s details: Name, Address/Postcode, Telephone number: Date of birth: Name of patients General Medical Practitioner: Further to our telephone conversation I would be grateful if you could see the above named patient, as a matter of priority. Reasons for referral: Presenting complaint History of presenting complaint, including previous treatment Social history: Occupation, family details, Smoking: number per day /number of years Alcohol: number of units /day Medical and drug history Clear statement of clinical examination The patient’s level of understanding and concerns about their mucosal abnormality. Yours sincerely, General Dental Practitioner Diagnostic delays Patient delay is generally defined as the time from the patient's first awareness of a symptom to seeking their first consultation with a healthcare professional. [11,12] Professional delay is defined either as the time from the first consultation with a healthcare professional to the first consultation with a treating specialist, [12,13]or to the definitive diagnosis being made, , [14,15] or to the patient being admitted for definitive treatment, or as the time from the first consultation until a referral letter is sent to a specialist unit. [16] We would suggest the use of professional delay for the whole time from the patient's first consultation to their commencing definitive treatment. This is made up of referral delay (time from consultation to referral being made), appointment delay (time to appointment at specialist centre) and treatment delay (time from diagnosis to definitive treatment commencing). [16] The timely diagnosis and subsequent management of malignant lesions is well known to provide the best prognosis. Dental professionals are ideally situated to recognize potentially malignant lesions in the oral cavity. [17] A systematic extra-oral and intra-oral examination of the oral, head and neck region should be an integral part of all routine dental examinations and is considered as the most suitable screening method for malignant and premalignant lesions. Patient factors also play an important role in the early detection, as some patients do not attend regular dental assessments for social and financial reasons. [11] The delay in identification, referral and diagnosis will increase the chance of metastatic spread and therefore upstage the disease. [18] The five-year survival will therefore reduce from 90% for stage I disease to 30–40% for stage IV disease. [19] 4 Conclusions The primary dental healthcare practitioner and team, being in regular contact with patients and their families, are in the ideal position to give advice on the risk factors associated with oral cancer and to examine for oral cancer and potentially malignant lesions. Prevention in the form of smoking cessation and sensible drinking advice should be offered. Dentists should consider this in terms of a common risk factor approach: as smoking is relevant to oral cancer, but also to periodontal disease and general health. [20] Examination of the oral mucosa should form part of all patients’ routine checkup. Dentists have an important initial and continuing counseling role for patients with suspected oral cancer and for those diagnosed. To facilitate this, communication pathways should be established between primary and secondary care and referral protocols should be in place. There is a need for improved awareness of the roles of the oral cancer specialist care team and of the general dental practitioner by each other, to establish a greater integrated approach in the overall management of patients with oral cancer making the patient journey smoother, more effective and improving outcome. SUMMERY TABLE 1. APPROACH TO ORAL CANCER SCREENING 1. Examination for Every patient must be explored for potential malignant and early diagnosis of premalignant lesions each time a dental check-up is performed. A oral cancer particularly thorough examination is required on smokers, heavy drinkers or on patients elder than 40. 2. Referral scheme When a suspicious - If the clinician feels qualified for oral lesions lesion is detected, biopsy and confident, he/she can suspicious for is the only method to perform the biopsy and refer the Malignancy ascertain whether or not patient to a specialized centre in it is malignant. The case of malignancy. clinician can opt for two - Refer the patient directly to a actions: specialized centre or (maxillofacial surgery). 3. Information to It is essential for the Patient data: address, age, telephone include in the consultant to know number in order to contact the patient. referral letter certain data about the Brief medical history: relevant patient, the lesion and systemic disorders, medication he/she the clinical diagnosis in is taking and patient's physician and order to establish dentist telephone numbers. priorities within the Relevant facts of patient's social waiting list. Relevant history, including alcohol and tobacco data are: consumption. A detailed description of the lesion: data of appearance, site, size, color and consistency. Clinical diagnosis in order to allow categorization of the referral urgency. 5 SUMMERY TABLE 2. DENTAL COUNCIL REFERRAL SCHEME FOR LESIONS SUSPICIOUS FOR ORAL CANCER. Referral Example Refer to type Preferential - Ulceration that persists more than 14 Oral and Maxillofacial days after removing its hypothetical cause. surgery Service, - White, red or white-reddish lesions that Stomatology Service or cannot be scrapped off. any other specialized unit. - Evident lump - Localized pigmented lesion. Referral paths should be - Any oral lesion with suspicious features: agreed in advance with the rapid growth, infiltration, induration, local specialized units. fixation. - Non-visible but palpable intraoral lumps. - Non-explained orofacial pain that persists longer than 4 weeks. - Unexplained recent neck lump. - Unexplainde dysphagia lasting longer than 3 weeks. - Unexplained dental mobility lasting longer than 3 weeks that cannot be related to trauma or periodontal disease. - Unexplained osseous lesion. - Decrease of orofacial sensitivity and paralysis of unknown origin. Normal - Any other disorder requiring medicosurgical treatment. 6 استمارة اإلحالة ألمراض الفم .......... دائرة صح ........... قطاع الرعاي الصحي األولي في ............... أسم مركزالرعاي الصحي األولي في ..................أو أسم المركز التخصصي لطب األسنان ........... إحالة إلى شعبة جراحة الوجه والفكين في مستشفى ....... :عنوان المستشفى المحال اليها -: التاريخ -: العمر -: رقم الهاتف -: اسم المريض -: الجنس -: العنوان Chief complaint:History of present complaint:Medical and drug history:Previous treatment:Occupation:Social history:Smoking:number per day :Alcohol:number of units /day:Clinical examination:- Type of lesion:Size of lesion :Any associated symptoms:Lymph nodes involvement:Investigations:- family details :number of years:Site of lesion:Duration of lesion:- Differential diagnosis:Spot diagnosis:…………………………………………… ……………………………………………… ………………………………………….. ……………………………………………. ختم المركز -: اسم وتوقيع طبيب األسنان الممارس 7 References 1. Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:309-16. 2. Holmes JD, Dierks EJ, Homer LD, Potter BE. Is detection of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cancer by a dental health care provider associated with a lower stage at diagnosis? J Oral Maxillofac Surg.2003;61:285-91. 3. Kujan O, Glenny AM, Sloan P. Screening for oral cancer. Lancet.2005;366:1265-6. 4. Patton LL, Ashe TE, Elter JR, Southerland JH, Strauss RP.Adequacy of training in oral cancer prevention and screening as self-assessed by physicians, nurse practitioners, and dental health professionals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod.2006;102:758-64. 5. Higuchi KA, Cragg CE, Diem E, Molnar J, O’Donohue MS. Integrating clinical guidelines into nursing education. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2006;3:12. 6. 17. Speight PM, Palmer S, Moles DR, Downer MC, Smith DH, Henriksson M, et al. The costeffectiveness of screening for oral cancer in primary care. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:1-144. 7. 11. Singh P, Warnakulasuriya S. The two-week wait cancer initiative on oral cancer; the predictive value of urgent referrals to an oral medicine unit. Br Dent J. 2006;201:717-20. 8. 18. Carter LM, Ogden GR. Oral cancer awareness of undergraduate medical and dental students. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:44. 9. Hutchinson A, McIntosh A, Cox S, Gilbert C. Towards efficient guidelines: how to monitor guideline use in primary care. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7:1-97. 10. Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:1-72. 11. Ogden G, Cowpe J, Chisholm D. Costs of oral cancer screening. The Lancet 1991; 337: 920–921. 12. NHS Executive. Referral guidelines for suspected cancer. http://www.nature.com/bdj/journal/v198/n11/full/www.doh.gov.uk. Accessed October 2003 13. Kowalski LP, Franco EL, Torloni H, Fava AS, Sobrinho JA, Ramos G, Oliveira BV, Curado MP. Lateness of diagnosis of oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma: factors related to the tumour, the patient and health professionals. Oral Oncol, Eur J Cancer 1994; 30B: 167–173. 14. Wildt J, Bundgaard T, Bentzen SM. Delay in the diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Otolaryngol 1995; 20: 21–25. | PubMed | ISI | ChemPort | 15. Allison P, Locker D, Feine JS. The role of diagnostic delays in the prognosis of oral cancer: a review of the literature. Oral Oncol 1998; 34: 161–170. | Article | PubMed | ISI | ChemPort | 16. N M H McLeod1, N R Saeed2 & E A Ali, British Dental Journal 198, 681 - 684 (2005) Published online: 11 June 2005 | doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4812381 17. McIntyre G, Oliver R. Update on precancerous lesions. Dent Update 1999; 26: 382–386. 18. Porter S, Scully C. Oral malignancy and potential malignancy, good referrals benefit patients. Dental Practice 2001; 39: 15–16. 19. Hyde N, Hopper C. Oral cancer: the importance of early referral. The Practitioner 1999; 243: 753–763. 20. Salvi GE, Lawrence HP, Offenbacher S, Beck JD. Influence of risk factors on the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Periodontology 2000; 14:173-201. 8