Thesis Thomas Worley

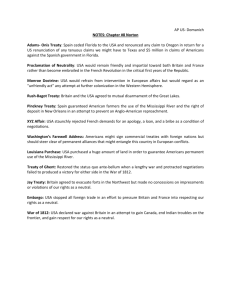

advertisement