Microsoft Word 2007 - UWE Research Repository

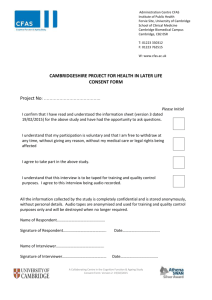

advertisement