Tips for volunteers teaching ESL

advertisement

http://writing.colostate.edu/guides/teaching/esl/

Getting Started: The Basics of Teaching

The following principles apply to almost any kind of teaching. Some of these points may

seem like common sense, yet these are the types of issues professional teachers spend

years learning and perfecting. Many of these ideas are adapted from Teaching By

Principles: An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy by H. Douglas Brown and How

To Teach Englishby Jeremy Harmer.

Make Lessons Interesting

Bored students won't remember much of the lesson. Don't talk for long blocks of

time. Instead, keep students involved and interacting with you and each other in

English. Some may come from cultures where teachers lecture and students listen

quietly. If interaction makes your students nervous, provide plenty of support by

giving clear and very specific directions. Say, "Yuko and Yan, you work together,"

rather than "everyone get into pairs." Vary the types of skills you practice and

activities you use, add games, and bring in real-life objects like a telephone, cook

book, or musical instrument. Vary your own dress or behavior patterns for a day.

Keep in mind, though, that some degree of predictability will be appreciated by

your students, fostering a feeling of safety.

Make Yourself Understandable

Simplify your vocabulary, grammar, and speaking speed to the degree necessary to

be understood, and keep any instructions simple and logical. New ESL teachers

frequently slow down the pace of their speech but forget to modify their

vocabulary and grammar for beginning students. As your students' English ability

increases, so should the complexity and speed of your English. Some of your

interaction at an intermediate level and most of it at an advanced level can use

natural grammar and speed, but make sure you slow down or repeat any highly

important points. Teach your learners how to ask for clarification when they need

it. Try to anticipate unknown vocabulary and be prepared to explain it.

Appropriate language modification gets easier with experience.

Motivate With Rewards

Learners will truly want to learn when they perceive a personal reward. To boost

internal motivation, remind them of the benefits that English can provide, such as

English-speaking friends, better job opportunities, easier shopping, or less stress at

the doctor's office, and then teach language that will bring them closer to those

benefits. Motivation can be boosted externally by praise and encouragement as

well as tangible rewards like prizes, certificates, or check marks on an attendance

chart. Motivation can be hindered by over-correction or teaching a topic that the

learner will not use in daily life.

Provide a Useful Context

Learners will remember material better and take more interest in it if it has

relevant contextual meaning. Arbitrary rote learning (word lists or grammar drills)

may be useful in solidifying language forms, but unless there's a real-world

application, sooner or later it's likely to be forgotten.

Remember that Native Language Affects English Learning

A learner's native language will provide a basis for figuring out how English works.

Sometimes the native language can affect English production. To illustrate, the

Japanese language does not use articles (a, an, the) so correct article usage is

frequently difficult for Japanese learners. Spanish uses idioms such as "I have

thirst" or "I have sleepiness" so Spanish speakers may forget to use "I am..." with an

adjective instead of a noun. Most teachers, however, have little if any

understanding of their students' native language. While a familiarity with the

native language may shed light on certain errors, it is certainly not essential. In

fact, intermediate and advanced students are often able to tell you whether a

specific error is related to their native language.

Don't Assume All Errors are Bad

Native language interference contributes to a gradual process of learning in which

language is refined over time to become more like natural English. For example, a

learner may progress through phrases such as "no I like peanuts," "I no like

peanuts," and finally, "I don't like peanuts." Teachers must not get discouraged

watching students exchange one error for another; this process is a natural part of

language learning. Selectively choose errors to work on rather than trying to fix

everything at once. Give priority to problems that hinder communication rather

than incorrect but understandable errors. With gentle corrective feedback,

students will keep improving.

Encourage Learners to Think in English

Too often ESL learners will get stuck in a habit of thinking in their native language

and then mentally translating what they want to say or write into English. This is

time consuming and frequently leads to confusion when direct translation isn't

possible. Thinking in English requires learners to use learned words, phrases, and

language structures to express original ideas without focusing too much on

language rules or translation. To illustrate, how would you change the statement

"Linda ate an apple" into a question? Of course, "Did Linda eat an apple?" More than

likely you didn't think about adding the modal 'do' (in the past tense 'did' because

'ate' is past tense) before the subject, changing the irregular verb 'ate' to 'eat' and

raising your vocal intonation at the end of the sentence. While it's unreasonable to

expect beginning ESL learners not to rely on native language translation to some

degree, one way you can minimize it is to explain new vocabulary using simple

English, drawings, or gestures and allow dictionary lookups only as a last resort.

You might also ask them to speak (or write if they are able) for several minutes

without stopping. At some point, mental translation will become cumbersome and

learners should begin developing an ability to use English independently from their

native language.

Build Confidence in Your Students

Learners must believe in their own ability to complete a task. Without selfconfidence, they are unlikely to take risks, and risk-taking is necessary in language

learning. Learners need to feel that it's safe to make mistakes. By trying out new

or less familiar language, they may find that they are indeed capable of more

communication than they thought. Try to reduce feelings of embarrassment when

mistakes are made, and give far more compliments than criticisms. Make some

tasks easy enough that everyone is guaranteed success.

Account for Different Learning Styles

Some people are hands-on learners, some like to watch, some like to have detailed

explanations. Some people learn better visually, others audibly. Some like to work

in groups, some work better individually. Language teaching should take a variety

of learning styles into account through varied activities.

Know Your Students

Learn how to pronounce students' names (or ask for easier nicknames) and then

remember and use them. Build trust with your students by building relationships

and being approachable. Make sure quiet students are included and more assertive

ones don't dominate the lesson.

Focus On Communication

Interaction requires communication, the transfer of a meaningful idea from one person to

another. Good teachers go beyond the building blocks of English such as vocabulary lists

or grammar drills to develop a learner's oral, written, and even non-verbal

communication skills. Every lesson should prepare your students for real-world interaction

in some way. Think meaningful and usable.

When communication breaks down, native speakers usually try to clarify any potentially

unclear items by asking questions and offering explanations. They ask for repetition or

more information, confirm that the other person has understood what was said, expand

on words or topics, or repeat back a paraphrase of what they just heard to confirm that

they got it right. This is one of the greatest communication skills, but it can be difficult

and ESL learners need to be taught how to do this in English.

Teachers bring communication into their lessons by guiding learners through tasks or

activities which require meaningful communication in a relevant context. Here are some

tips for making your lessons communicative:

Clarification Skills

Teach your students how to ask for clarification. The following phrases may serve

as a starting point and can be expanded or adapted to an appropriate language

level.

o Do you understand?

o Excuse me? / Could you repeat that?

o Once more. / One more time.

o Please speak more slowly.

o How do you spell that?

o Did you say ______?

o What does ______ mean?

o How do you say ______ in English?

I don't know.

I don't understand.

Pair and Group Work

When students must work with each other or one-on-one with you, they are forced

to communicate. Make sure you have taught them how to ask for clarification

when they don't understand something. If students share the same native

language, limit its use as much as possible. Information gap activities, role plays,

and collaborative problem solving are some communicative activities explained in

more detail in the activities section of this guide.

Individual Communication

Some types of communication are not highly interactive. For example, you can

have students give a speech, write a letter or composition, or report group work

results to the class. As long as they are producing original language to convey their

own thoughts, they are practicing communication.

Interactive Teaching

Specific practice activities aren't the only place where communication can occur.

While you are teaching your main lesson, you don't need to do all the talking.

Involve your students by asking them for related vocabulary words, the spelling of

a word they suggest, the past tense of verbs (especially irregular ones), examples

beyond those in the textbook, etc. Draw out what they already know and connect

it to their life experiences. For example, if your text contains the word 'allergy'

and you aren't sure if the students understand it, rather than simply teaching "an

allergy is..." and moving on, ask if anyone knows the meaning and can explain it,

what types of allergies the students can think of, and whether anyone has an

allergy. Ask for the spelling of the plural form, 'allergies.' If your students have a

lot to say, these side-tracks can become time-consuming. You will need to decide

how much time you will allow for this so you can still complete your lesson.

What Communication is Not

Some elements of your lesson will probably not be communicative. For example,

memorization, vocabulary lists, reading, listening tasks, grammar structures, and

pronunciation practice do not require any original language to be produced by the

learner, yet they are all valuable building blocks for communication. As a teacher,

you should be aware of the difference between what is communicative and what is

not and balance the two.

o

o

Language Levels

What do the terms beginner, intermediate, and advanced really mean? Unfortunately the

definitions vary among institutions. The following guide for oral communication ability,

though subjective, may be useful if your program does not have its own definitions of

performance standards:

True Beginner

o Very limited communication in English

o Uses gestures and 1-3 word utterances

Beginner

Communicates with difficulty and many errors

Very simple, unelaborated answers

Many hesitations

No ability to extend conversation

Uses simple grammar & vocabulary

Low Intermediate

o Communicates understandably with some errors

o Simple answers and little elaboration

o Attempts interactive conversation

o Attempts more complex grammar

High Intermediate

o Communicates fairly well

o Some elaboration, especially on familiar topics

o Can converse with errors and some hesitations

o Uses more complex grammar & vocabulary

Advanced

o Communicates well with occasional errors

o Converses with lots of elaboration and interaction

o Errors don't hinder communication

o Uses advanced grammar & vocabulary

o

o

o

o

o

Your volunteer program may or may not have its own system for assessing student

language levels. If you work with a student one-on-one, knowing the 'level' is not as

critical as knowing the student; you will soon discover strengths and weaknesses and

develop a sense of what your student can or can't handle. However, if you work with

more than one learner, your task will be much easier if they are all near the same

language level. For this reason, many programs test language levels for all new students

for placement purposes. The following is a sample intake test based on the above

performance descriptions. Testing instructions are found on page two. An accompanying

page of drawings has not been included due to copyright.

ESL Evaluation

Introduce yourself first!

Level 1: Beginner

Level 2: Low – Intermediate

few words, many hesitations, no ability

to extend conversation

simple answers, little conversation,

many errors

What’s your name?

Where are you from?

What time is it?

How long have you lived in

Colorado?

What did you do yesterday?

Do you have a hobby? >> What is

it?

Pictures:

Where is the teacher?

Where are the flowers?

What is Jane doing?

(point to picture 4)

How many pictures are there?

Pictures:

What are Mike and Sue doing?

>> Why?

(point to picture 3)

What’s happening in this

picture?

(point to picture 5)

Where are the people in picture

1?

Level 3: Intermediate – High

Level 4: Advanced

some elaboration, can converse with

errors and some hesitations

lots of elaboration & interaction,

errors don’t hinder communication

Have you ever taken the TOEFL

test?

>> What was your score?

(paper 525 / computer 197 >> try

L4)

Can you tell me what some of the

differences are between Colorado

and your country?

What’s your favorite season?

>> Why?

What’s the most memorable

vacation you’ve ever had? >>

Can you tell me more about it?

Can you describe the health care

system in your country? >> What

do you think about it?

What do you want to be doing in

five years? >> Do you think it’s

possible?

If I were to go to your country as

a tourist, what should I see?

Pictures:

Pictures:

In picture 1, who will not get

wet?

What happened to Sam and what

should he do next?

What did Tom Smith do? >> Why?

Choose one of these pictures and

tell me a short story about it.

Instructions for testing:

1. Introduce yourself first.

2. If the student appears responsive and able to converse, begin with level 3 questions. If

the student appears confused or very shy, begin with level 2.

3. Speak at a normal pace while testing, slowing down and offering explanations only if

the student is unable to understand. (If this occurs often, try a lower level.)

4. When finished, please circle the appropriate level number on the intake form.

Levels 1 and 2 are pre-conversational, 3 and 4 are conversational

Level 3 questions: Ask a couple of questions of your choice and listen for hesitations,

errors, and vocabulary problems. If you are maintaining a conversation but find yourself

asking for clarification or correcting the student frequently, or if the pace is slow, you

have a level 3 student. If you experience no difficulty, move on to level 4 without asking

all level 3 questions. If you have a lot of trouble maintaining conversation, drop down to

level 2 questions.

Level 4 questions: If the student is able to continue with little difficulty and gives

extended answers and keeps a steady pace with few hesitations, you have a level 4

student. Some errors are expected but they should not hinder communication. If the

student has difficulty, go back to level 3 questions. You may have a level 3 or level 3/4

student.

Note: a high TOEFL score does not mean the student is automatically level 4.

Level 2 questions: Ask a couple of questions and if the student answers quickly and easily,

try level 3 without asking all level 2 questions. If level 3 is too difficult, you may have a

level 2/3 student. If the student does not understand or cannot answer easily, move to

level 1.

Level 1 questions: Whether or not the student can answer any of the questions, you have

a level 1 student if level 2 is too difficult.

Used by permission. This is an ESL intake test used by International Students, Inc. (a

nonprofit organization) at Colorado State University. It assesses oral communication

ability. A separate page of drawings has not been included due to copyright. The

drawings are: 1) Ann and Bill standing in the rain, Sara and Peter walking with an

umbrella; 2) Sam with a paintbrush in his hand and his foot stuck in a paint bucket,

another painter on a ladder behind him; 3) Mike and Sue reading a travel guide; 4) Jane

sitting on a stack of books, reading; 5) Peter Jones handing Sally Jones a pot of flowers;

6) Tom Smith carrying shopping bags filled with painting supplies, a paint store with a

'big sale' sign behind him; 7) Mrs. Adams sitting behind a table with a book and an apple,

pointing to a math equation on a blackboard.

CONVERSATION Consider these tips to become an effective conversation partner.

Speak at a Natural Pace

Slow down only when absolutely necessary. Your student will probably not

understand everything, which provides an opportunity for the student to practice

asking for clarification. If you are asked to repeat something, repeat your exact

words. Then you can offer a paraphrase if there is still misunderstanding.

Check Comprehension

Many students will nod as you speak even though they don't understand what

you're saying. They may be hoping that you will eventually say something that

connects the bits and pieces they have managed to absorb, or they may be

signaling that they heard your voice. If your student nods a lot, gets a blank look,

or becomes silent, directly ask whether he or she understands. If not, you may

need to slow down or at least simplify your grammar and vocabulary.

Elaborate Topics

Stay on one topic as long as you can. This helps a student learn to carry a

conversation rather than just answering a series of unrelated questions. Encourage

the student to ask you questions about the topic, too.

Bring Objects to Stimulate Conversation

This is great for shy students. Try family or vacation photos, cookbooks with

pictures, board games, library books about your student's country or other topics

with lots of pictures, and short, current newspaper or magazine articles.

Avoid Correcting Homework

Students may bring their ESL homework and ask you to check the answers. Not only

does this take away time from developing conversation skills, it can potentially

force you into the role of a teacher explaining why an answer is right or wrong. If

you are willing to provide this service to your student, try to do it before or after

your allotted conversation partner time.

Minimize Error Correction

Constant correction slows down conversation and hinders the development of

fluency. Correct only those errors that block communication.

Vary the Scenery

Unless you must meet at a fixed location, occasionally vary your meeting place.

Try a park, library, home, coffee shop, nature walk, etc.

Keep a Journal

Write down what you talked about or did so you can use it again or refine it for

future use

Recognize Stages of Cultural Adjustment

Stages of initial happiness but confusion, hostile attitudes from continued

frustration and confusion, humor and tolerance as new cultural rules are

understood more, and feeling at home with an understanding of cultural

expectations are all common during cultural adjustment, and students may skip or

repeat some of these stages. Try to be aware of cultural adjustment issues and

help your student understand and adapt to American culture.

Refer Problems to Qualified Program Personnel

As you develop trust, you may find your student confiding in you about serious

problems (medical, legal, landlord, family, etc.) which you may not be qualified to

handle. If you aren't trained as a counselor, resist the urge to be one. Express

compassion, but refer the student to a program leader or assist with getting help

from an appropriate professional office or public service.

Here are some conversation questions to help you get started. Most of them are suitable

for low intermediate and above. You can adapt the complexity of the questions to your

student's level.

Conversation Questions for the ESL/EFL Classroom

Many categorized lists of questions to facilitate conversation.

Conversation Groups

You may be a leader of a conversation group or perhaps a classroom assistant assigned to

a few students for a classroom activity. Again, your role is more of a facilitator than a

teacher. The main goal is conversational English practice.

Encourage Friendship

Help the group members get to know each other and become friends through pair

interviews, icebreaker games, or even social activities. Students will speak more

freely when they feel a connection to other group members.

Include Everyone

If you have a very talkative student who tends to dominate the conversation, find

ways to limit speaking time and ask others for their opinions. If you have a shy or

silent student, make sure to specifically include him or her. Be careful, though.

The silence may be due to lower language ability, so begin by asking easy yes/no

or either/or questions rather than open-ended opinion questions. It may also be

helpful to sit right next to more talkative students and across from quieter ones if

you are in a circle.

Monitor Native Language Use

Discourage native language use as much as possible. Students may ask each other

what an English vocabulary word means because they don't want to interrupt the

conversation to ask in English. Explain that it is polite and acceptable to say,

"Excuse me, what does ______ mean?" Students may also ask each other how to say

a native language word in English. This is less problematic because the student's

goal is to use English. If your group has mixed languages, splitting up samelanguage friends will discourage native language use, but they may also speak less

English if they are seated between classmates with whom they are less

comfortable. You will need to tune in to each student's personality when deciding

whether or not to separate same-language speakers.

Clarify Expectations

Recognize that some students may come from cultures where education is very

formal and classes don't include discussion groups. They may be uncomfortable

with the casual American style and need help to adjust. Explain your expectations

about your seating arrangement, starting on time or chatting first, who can speak

and when, and in what circumstances students may speak their native language

English Skills

When we think of English skills, the 'four skills' of listening, speaking, reading, and

writing readily come to mind. Of course other skills such as pronunciation,

grammar, vocabulary, and spelling all play a role in effective English

communication. The amount of attention you give to each skill area will depend

both the level of your learners as well as their situational needs. Generally

beginners, especially those who are nonliterate, benefit most from listening and

speaking instruction with relatively little work on reading and writing. As fluency

increases, the amount of reading and writing in your lessons may also increase.

With advanced learners, up to half of your lesson time can be spent on written

skills, although your learners may wish to keep their focus weighted toward oral

communication if that is a greater need.

Teaching Listening

Listening skills are vital for your learners. Of the 'four skills,' listening is by far the most

frequently used. Listening and speaking are often taught together, but beginners,

especially non-literate ones, should be given more listening than speaking practice. It's

important to speak as close to natural speed as possible, although with beginners some

slowing is usually necessary. Without reducing your speaking speed, you can make your

language easier to comprehend by simplifying your vocabulary, using shorter sentences,

and increasing the number and length of pauses in your speech.

There are many types of listening activities. Those that don't require learners to produce

language in response are easier than those that do. Learners can be asked to physically

respond to a command (for example, "please open the door"), select an appropriate

picture or object, circle the correct letter or word on a worksheet, draw a route on a

map, or fill in a chart as they listen. It's more difficult to repeat back what was heard,

translate into the native language, take notes, make an outline, or answer comprehension

questions. To add more challenge, learners can continue a story text, solve a problem,

perform a similar task with a classmate after listening to a model (for example, order a

cake from a bakery), or participate in real-time conversation.

Good listening lessons go beyond the listening task itself with related activities before

and after the listening. Here is the basic structure:

Before Listening

Prepare your learners by introducing the topic and finding out what they already

know about it. A good way to do this is to have a brainstorming session and some

discussion questions related to the topic. Then provide any necessary background

information and new vocabulary they will need for the listening activity.

During Listening

Be specific about what students need to listen for. They can listen for selective

details or general content, or for an emotional tone such as happy, surprised, or

angry. If they are not marking answers or otherwise responding while listening, tell

them ahead of time what will be required afterward.

After Listening

Finish with an activity to extend the topic and help students remember new

vocabulary. This could be a discussion group, craft project, writing task, game,

etc.

The following ideas will help make your listening activities successful.

Noise

Reduce distractions and noise during the listening segment. You may need to close

doors or windows or ask children in the room to be quiet for a few minutes.

Equipment

If you are using a cassette player, make sure it produces acceptable sound quality.

A counter on the machine will aid tremendously in cueing up tapes. Bring extra

batteries or an extension cord with you.

Repetition

Read or play the text a total of 2-3 times. Tell students in advance you will repeat

it. This will reduce their anxiety about not catching it all the first time. You can

also ask them to listen for different information each time through.

Content

Unless your text is merely a list of items, talk about the content as well as specific

language used. The material should be interesting and appropriate for your class

level in topic, speed, and vocabulary. You may need to explain reductions (like

'gonna' for 'going to') and fillers (like 'um' or 'uh-huh').

Recording Your Own Tape

Write appropriate text (or use something from your textbook) and have another

English speaker read it onto tape. Copy the recording three times so you don't

need to rewind. The reader should not simply read three times, because students

want to hear exact repetition of the pronunciation, intonation, and pace, not just

the words.

Video

You can play a video clip with the sound off and ask students to make predictions

about what dialog is taking place. Then play it again with sound and discuss why

they were right or wrong in their predictions. You can also play the sound without

the video first, and show the video after students have guessed what is going on.

Homework

Give students a listening task to do between classes. Encourage them to listen to

public announcements in airports, bus stations, supermarkets, etc. and try to write

down what they heard. Tell them the telephone number of a cinema and ask them

to write down the playing times of a specific movie. Give them a tape recording of

yourself with questions, dictation, or a worksheet to complete.

Look for listening activities in the Activities and Lesson Materials sections of this guide. If

your learners can use a computer with internet access and headphones or speakers, you

may direct them toward the following listening practice sites. You could also assign

specific activities from these sites as homework. Teach new vocabulary ahead of time if

necessary.

Teaching Speaking

Speaking English is the main goal of many adult learners. Their personalities play a large

role in determining how quickly and how correctly they will accomplish this goal. Those

who are risk-takers unafraid of making mistakes will generally be more talkative, but with

many errors that could become hard-to-break habits. Conservative, shy students may take

a long time to speak confidently, but when they do, their English often contains fewer

errors and they will be proud of their English ability. It's a matter of quantity vs. quality,

and neither approach is wrong. However, if the aim of speaking is communication and

that does not require perfect English, then it makes sense to encourage quantity in your

classroom. Break the silence and get students communicating with whatever English they

can use, correct or not, and selectively address errors that block communication.

Speaking lessons often tie in pronunciation and grammar (discussed elsewhere in this

guide), which are necessary for effective oral communication. Or a grammar or reading

lesson may incorporate a speaking activity. Either way, your students will need some

preparation before the speaking task. This includes introducing the topic and providing a

model of the speech they are to produce. A model may not apply to discussion-type

activities, in which case students will need clear and specific instructions about the task

to be accomplished. Then the students will practice with the actual speaking activity.

These activities may include imitating (repeating), answering verbal cues, interactive

conversation, or an oral presentation. Most speaking activities inherently practice

listening skills as well, such as when one student is given a simple drawing and sits behind

another student, facing away. The first must give instructions to the second to reproduce

the drawing. The second student asks questions to clarify unclear instructions, and

neither can look at each other's page during the activity. Information gaps are also

commonly used for speaking practice, as are surveys, discussions, and role-plays.

Speaking activities abound; see the Activities and Further Resources sections of this guide

for ideas.

Here are some ideas to keep in mind as you plan your speaking activities.

Content

As much as possible, the content should be practical and usable in real-life

situations. Avoid too much new vocabulary or grammar, and focus on speaking with

the language the students have.

Correcting Errors

You need to provide appropriate feedback and correction, but don't interrupt the

flow of communication. Take notes while pairs or groups are talking and address

problems to the class after the activity without embarrassing the student who

made the error. You can write the error on the board and ask who can correct it.

Quantity vs. Quality

Address both interactive fluency and accuracy, striving foremost for

communication. Get to know each learner's personality and encourage the quieter

ones to take more risks.

Conversation Strategies

Encourage strategies like asking for clarification, paraphrasing, gestures, and

initiating ('hey,' 'so,' 'by the way').

Teacher Intervention

If a speaking activity loses steam, you may need to jump into a role-play, ask more

discussion questions, clarify your instructions, or stop an activity that is too

difficult or boring.

Teaching Reading

We encounter a great variety of written language day to day -- articles, stories, poems,

announcements, letters, labels, signs, bills, recipes, schedules, questionnaires, cartoons,

the list is endless. Literate adults easily recognize the distinctions of various types of

texts. This guide will not cover instruction for learners with little or no literacy in their

native language; you will need to work intensively with them at the most basic level of

letter recognition and phonics.

Finding authentic reading material may not be difficult, but finding materials appropriate

for the level of your learners can be a challenge. Especially with beginners, you may need

to significantly modify texts to simplify grammar and vocabulary. When choosing texts,

consider what background knowledge may be necessary for full comprehension. Will

students need to "read between the lines" for implied information? Are there cultural

nuances you may need to explain? Does the text have any meaningful connection to the

lives of your learners? Consider letting your students bring in their choice of texts they

would like to study. This could be a telephone bill, letter, job memo, want ads, or the

back of a cereal box. Motivation will be higher if you use materials of personal interest to

your learners.

Your lesson should begin with a pre-reading activity to introduce the topic and make sure

students have enough vocabulary, grammar, and background information to understand

the text. Be careful not to introduce a lot of new vocabulary or grammar because you

want your students to be able to respond to the content of the text and not expend too

much effort analyzing the language. If you don't want to explain all of the potentially new

material ahead of time, you can allow your learners to discuss the text with a partner and

let them try to figure it out together with the help of a dictionary. After the reading

activity, check comprehension and engage the learners with the text, soliciting their

opinions and further ideas orally or with a writing task.

Consider the following when designing your reading lessons.

Purpose

Your students need to understand ahead of time why they are reading the material

you have chosen.

Reading Strategies

When we read, our minds do more than recognize words on the page. For faster

and better comprehension, choose activities before and during your reading task

that practice the following strategies.

o Prediction: This is perhaps the most important strategy. Give your students

hints by asking them questions about the cover, pictures, headlines, or

format of the text to help them predict what they will find when they read

it.

o Guessing From Context: Guide your students to look at contextual

information outside or within the text. Outside context includes the source

of the text, its format, and how old it is; inside context refers to topical

information and the language used (vocabulary, grammar, tone, etc.) as

well as illustrations. If students have trouble understanding a particular

word or sentence, encourage them to look at the context to try to figure it

out. Advanced students may also be able to guess cultural references and

implied meanings by considering context.

o Skimming: This will improve comprehension speed and is useful at the

intermediate level and above. The idea of skimming is to look over the

entire text quickly to get the basic idea. For example, you can give your

students 30 seconds to skim the text and tell you the main topic, purpose,

or idea. Then they will have a framework to understand the reading when

they work through it more carefully.

o Scanning: This is another speed strategy to use with intermediate level and

above. Students must look through a text quickly, searching for specific

information. This is often easier with non-continuous texts such as recipes,

forms, or bills (look for an ingredient amount, account number, date of

service, etc.) but scanning can also be used with continuous texts like

newspaper articles, letters, or stories. Ask your students for a very specific

piece of information and give them just enough time to find it without

allowing so much time that they will simply read through the entire text.

Silent Reading vs. Reading Aloud

Reading aloud and reading silently are really two separate skills. Reading aloud

may be useful for reporting information or improving pronunciation, but a reading

lesson should focus on silent reading. When students read silently, they can vary

their pace and concentrate on understanding more difficult portions of the text.

They will generally think more deeply about the content and have greater

comprehension when reading silently. Try extended silent reading (a few pages

instead of a few paragraphs, or a short chapter or book for advanced students) and

you may be surprised at how much your learners can absorb when they study the

text uninterrupted at their own pace. When introducing extended texts, work with

materials at or slightly below your students' level; a long text filled with new

vocabulary or complex grammar is too cumbersome to understand globally and the

students will get caught up in language details rather than comprehending the text

as a whole.

Teaching Writing

Good writing conveys a meaningful message and uses English well, but the message is

more important than correct presentation. If you can understand the message or even

part of it, your student has succeeded in communicating on paper and should be

praised for that. For many adult ESL learners, writing skills will not be used much

outside your class. This doesn't mean that they shouldn't be challenged to write, but

you should consider their needs and balance your class time appropriately. Many

adults who do not need to write will enjoy it for the purpose of sharing their thoughts

and personal stories, and they appreciate a format where they can revise their work

into better English than if they shared the same information orally.

Two writing strategies you may want to use in your lessons are free writing and

revised writing. Free writing directs students to simply get their ideas onto paper

without worrying much about grammar, spelling, or other English mechanics. In fact,

the teacher can choose not to even look at free writing pieces. To practice free

writing, give students 5 minutes in class to write about a certain topic, or ask them to

write weekly in a journal. You can try a dialog journal where students write a journal

entry and then give the journal to a partner or the teacher, who writes another entry

in response. The journals may be exchanged during class, but journal writing usually

is done at home. The main characteristic of free writing is that few (if any) errors are

corrected by the teacher, which relieves students of the pressure to perform and

allows them to express themselves more freely.

Revised writing, also called extended or process writing, is a more formal activity in

which students must write a first draft, then revise and edit it to a final polished

version, and often the finished product is shared publicly. You may need several class

sessions to accomplish this. Begin with a pre-writing task such as free writing,

brainstorming, listing, discussion of a topic, making a timeline, or making an outline.

Pairs or small groups often work well for pre-writing tasks. Then give the students

clear instructions and ample time to write the assignment. In a class, you can

circulate from person to person asking, "Do you have any questions?" Many students

will ask a question when approached but otherwise would not have raised a hand to

call your attention. Make yourself available during the writing activity; don't sit at a

desk working on your next lesson plan. Once a rough draft is completed, the students

can hand in their papers for written comment, discuss them with you face to face, or

share them with a partner, all for the purpose of receiving constructive feedback.

Make sure ideas and content are addressed first; correcting the English should be

secondary. Finally, ask students to rewrite the piece. They should use the feedback

they received to revise and edit it into a piece they feel good about. Such finished

pieces are often shared with the class or posted publicly, and depending on the

assignment, you may even choose to 'publish' everyone's writing into a class booklet.

Tactful correction of student writing is essential. Written correction is potentially

damaging to confidence because it's very visible and permanent on the page. Always

make positive comments and respond to the content, not just the language. Focus on

helping the student clarify the meaning of the writing. Especially at lower levels,

choose selectively what to correct and what to ignore. Spelling should be a low

priority as long as words are recognizable. To reduce ink on the page, don't correct all

errors or rewrite sentences for the student. Make a mark where the error is and let

the student figure out what's wrong and how to fix it. At higher levels you can tell

students ahead of time exactly what kinds of errors (verbs, punctuation, spelling,

word choice) you will correct and ignore other errors. If possible, in addition to any

written feedback you provide, try to respond orally to your student's writing, making

comments on the introduction, overall clarity, organization, and any unnecessary

information.

Consider the following ideas for your writing lessons.

Types of Tasks

Here are some ideas for the types of writing you can ask your students to do.

o Copying text word for word

o Writing what you dictate

o Imitating a model

o Filling in blanks in sentences or paragraphs

o Taking a paragraph and transforming certain language, for example changing all

verbs and time references to past tense

o Summarizing a story text, video, or listening clip (you can guide with questions or

keywords)

o Making lists of items, ideas, reasons, etc. (words or sentences depending on level)

o Writing what your students want to learn in English and why

o Writing letters (complaint, friend, advice) - give blank post cards or note cards or

stationery to add interest; you can also use this to teach how to address an

envelope

o Organizing information, for example making a grid of survey results or writing

directions to a location using a map

o Reacting to a text, object, picture, etc. - can be a word or whole written piece

Format

Clarify the format. For an essay, you may specify that you want an introduction, main

ideas, support, and a conclusion. For a poem, story, list, etc., the format will vary

accordingly, but make sure your students know what you expect.

Model

Provide a model of the type of writing you want your students to do, especially for

beginners.

Editing

Consider giving students a checklist of points to look for when editing their own work.

Include such things as clear topic sentences, introduction and conclusion, verb tenses,

spelling, capitalization, etc.

Correction

Minimize the threatening appearance of correction. Instead of a red pen, use green or blue

or even pencil, as long as it's different from what the student used. Explain to the students

that you will use certain symbols such as VT for verb tense or WO for word order, and be

very clear whether a mark (check mark, X, star, circle) means correct or incorrect as this

varies among cultures.

Teaching Grammar

Grammar is often named as a subject difficult to teach. Its technical language and

complex rules can be intimidating. Teaching a good grammar lesson is one thing, but

what if you're in the middle of a reading or speaking activity and a student has a grammar

question? Some students may have studied grammar in their home countries and be

surprised that you don't understand, "Does passive voice always need the past participle?"

But even if your student's question is simple and jargon-free, explaining grammar is a skill

you will need to acquire through practice. If you don't know how to explain it on the spot,

write down the specific sentence or structure in question and tell the student you will

find out. There are several resources below that can help you understand and explain

various grammar issues.

Consider the following as you integrate grammar into your lessons.

Acknowledge your role.

As a volunteer, you aren't expected to be a grammar expert. You may have

difficulty explaining the 'why' behind grammar points, but you can recognize 'right'

and 'wrong' wording and your students will still benefit from your English

sensibility.

Find good lesson plans.

It's difficult to make a good grammar lesson from scratch, so any searching you do

for appropriate grammar lessons in textbooks or on the Internet will be time well

spent. See the Lesson Materials section of this guide for possible resources.

Use meaningful texts.

The sentences you use to teach and practice grammar shouldn't be random. Choose

material that is relevant. For example, if your learners are preparing for

citizenship or need workplace English, use these contexts to create appropriate

examples. If possible, bring in real-life, authentic texts to illustrate your points.

Teach basic grammar words.

Although you need not be fluent in grammar jargon, it's a good idea to teach at

least some vocabulary (noun, verb, past tense, etc.) to assist you in your

explanations. Intermediate and advanced students may be familiar with many such

words already. As a practice activity, you can choose 2-3 parts of speech, specify

different symbols for each (underline, circle, box), and have students mark their

occurrences in a sentence or paragraph.

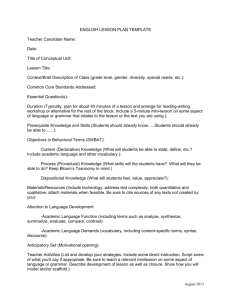

How To Plan A Lesson

Whether you use published ESL resources or plan your lesson from scratch, you will need a

basic structure. With some experience, you may only need to jot down a quick list of

topics and activities and then gather your materials together, but especially for new

teachers, it's usually helpful to write a complete lesson plan. Consider the following

framework.

Goals/Purpose

Decide which communication skills you wish to develop. Will you focus on reading?

writing? listening? speaking/pronunciation? a combination of these? In what

context? Consider a useful application for the language you will practice, things

such as taking phone messages, using the post office, or interviewing for a job.

These types of specific skills are sometimes referred to as "competencies."

Seemingly non-interactive themes like gardening or holidays are fair game, as long

as you integrate communicative activities.

Beginning

It's often a good idea to begin with some kind of warm-up activity to help the

learners focus on English and block out the distractions of daily life. This doesn't

necessarily need to be connected thematically to the rest of the lesson, but it's

nice if it is. Warm-ups usually take 5-15 minutes and practice material the learners

already know. Avoid new material in a warm-up because the goal of a warm-up is

to diffuse inhibitions and help students transition into English thinking and

speaking. A game-like atmosphere can help capture student interest, or you may

choose a quick review of the last lesson or homework. When reviewing, ask

learners what they remember and then fill in missing pieces rather than simply

summarizing the last lesson for them.

Middle

Most of your meeting time will probably be spent focused on one or two themes.

Present new material and give learners a chance to practice it thoroughly. You

may want to include pair or group work, silent reading/writing, games, or

conversational discussion. Your lessons will be more interesting if you use real-life

materials to support the text. For example, if the lesson theme is telling time,

bring in a large clock with adjustable hands to demonstrate with. Show a video of

a job interview, bring in a rental application, play a recorded clip from the radio,

share photos of your family. Try to incorporate something outside of the textbook

or printed lesson every time you meet.

End

Especially if the lesson content has been challenging, end by reviewing what what

was covered as well as what the learners already know. By finishing with

something familiar, learners will leave with the impression that English isn't too

difficult after all.

You can use the following reproducible worksheet to design a thoughtful and complete

lesson plan. You may choose to omit a section or add activities based on the time you

have. Use the "Time" column on the worksheet for estimating the amount of time you

wish to spend on each section. If you find during your lesson that your estimate was

incorrect, you can adjust by adding or cutting another activity. New teachers frequently

over-estimate the time needed for an activity, so it's wise to have some backup ideas to

fill in leftover time. Write any handouts or real-life objects you will need in the

"Notes/Materials" column.

Lesson Preparation

The first step of preparation is to plan your lesson. Once you have decided what to teach

and how to teach it, look at your lesson and think about ways to expand it, and make

note of what else needs to be done before your class. What can you bring to add interest?

What will you photocopy and how many copies will you need? If you copy double-sided

and have an odd number of pages, is there something fun like a cartoon or tongue twister

you can put on the last blank side?

In addition to preparing a specific lesson every day or week, it's helpful to build yourself a

collection of potential ESL resources to draw on as needed. Think about upcoming

holidays or future themes in your textbook. Create an organized storage system from the

beginning or you may find your growing collection of pictures, handouts, and games

becoming unmanageable. Label all important personal items with your name. Here are

some ideas for lesson preparation:

Gather Basic Teaching Items

These will make planning and teaching easier.

o Good textbook or lesson (perhaps from the Internet)

o Small white board with pens, if you don't have access to a classroom board

o Blank paper (a student may ask for some)

o Regular or picture dictionary

o List of extra activities to fill leftover time (see the Activities section of this

guide)

Collect Useful Materials

Be sure to protect your materials because they may be handled many times. Slip

paper materials into page protectors or magnetic photo album pages, glue them

onto card stock, or laminate them.

o Cut out magazine pictures

o Select photographs of a vacation, family members, etc.

o Collect travel brochures and public service pamphlets

o Save interesting newspaper or magazine articles

o Save cartoons or humorous drawings

o Borrow library books with pictures, such as children's stories or travel guides

o Collect blank note cards or postcards for students to write on

o Consider board or card games

o Bring children's building blocks or legos

o Bring objects like clothing, fruits, a clock, canned food, etc.

o Find relevant handouts on the internet (see the Lesson Materials section of

this guide)

Make Your Own ESL Materials

Creativity helps, but you don't need to be a creative genius to make useful

materials to accompany your lessons.

o Write simple quizzes

o Write dialogs and role plays

o Write tongue twisters to focus on a problem sound

o Create crossword puzzles using vocabulary words

o Make alphabet or vocabulary flash cards

o Create games, drawings, posters, etc.

o Use a craft with your lesson, such as cutting snow flakes or decorating

Easter eggs

Use Available Technology

If you have access to a TV and VCR, cassette/CD player, overhead projector, or

even a computer, use them to bring variety to your lessons. Always be prepared

with a non-technical backup activity should your equipment unexpectedly fail.

o Videotape TV commercials or news clips, or borrow a library video

o Copy outlines, diagrams, cartoons, etc. onto overhead transparencies

o Tape record a few minutes of radio talk

o Choose a popular song to play and make a worksheet of the song lyrics with

missing word blanks; if you use a cassette, record the song 2-3 times for

easy playback

o Play background (instrumental) music while students work on an activity

o Find a website your students can use for ESL activities (see the Further

Resourcessection of this guide)

Lesson Planning Tips

Lesson planning will help you teach with confidence. The longer your class session, the

more important it is to have a good lesson plan. Here are some tips to consider.

Plan Alternative Activities

Always have one or two alternative activities in case the material you've selected

doesn't take all the time you thought it would. How will you fill an extra 10

minutes? 20 minutes?

Build on Previous Material

Try to continuously practice material that you've covered recently. It's often

possible to teach the same theme several sessions in a row which can help ingrain

vocabulary and concepts.

Balance the Challenge of Content and Activity Type

If your content is challenging, choose activities that are relatively easy to do like

fill-in-the-blank exercises or guided discussion questions. If your content is fairly

simple, try more challenging activities like role plays or problem-solving.

Create Your Own Materials

Build your own library of materials to support your lessons. You can find several

ideas in the Lesson Preparation section of this guide. Be creative. If you invest

some time into developing and collecting materials, you'll cut down on your

preparation time when you are actually planning lessons.

Center Lessons Around the Student

Keep the focus on the learners and minimize the time you spend talking as a

teacher. In other words, make the lesson as interactive as possible. Focus on

communication.

Assess Needs

Periodically take time to think through your particular learners' needs. Think about

cultural factors as well as language deficiencies. This can help you prioritize what

you choose to study. Are any of your students dealing with culture shock? What

kind of language skills might help alleviate it? Try asking the students themselves

what they would like to learn.

Keep a Log

After each class, write a brief log of what you did. Include notes about what

worked or didn't with ideas for improvement. Write down specific page numbers

you covered in a textbook. You could also keep your lesson plans collected

together, making sure to write notes on them about the success of various

activities and whether you modified the lesson during class.

Warm-up Ideas

Warm-ups help your learners put aside their daily distractions and focus on English. If

they haven't used English all day, they may take a little while to shift into it. Warm-ups

also encourage whole-group participation which can build a sense of community within

the group. For new groups, see the list of ice breakers further down.

Brainstorm (any level, individual or group)

Give a topic and ask learners to think of anything related to it. Write the responses

for all to see, or ask a volunteer to do the writing. You can use this to elicit

vocabulary related to your lesson.

Question of the Day (intermediate-advanced, individual or group)

Ask 1-2 simple questions and give learners 5 minutes to write their answers.

Randomly choose a few people to share their answers with the group.

Yesterday (intermediate, group)

Have a learner stand in front of the group and make one statement about

yesterday, such as "Yesterday I went shopping." Then let everyone else ask

questions to learn more information, such as "Who did you go with?" "What did you

buy?" "What time did you go?" etc. Try this with 1-2 different learners each day.

Describe the Picture (any level, group)

Show a picture and have learners take turns saying one descriptive thing about it.

Beginners can make simple observations like "three cats" while advanced students

can make up a story to go with the picture. They aren't allowed to repeat what

someone else said, so they need to pay attention when each person

speaks. Variation for individual: take turns with the teacher.

Criss-Cross (beginner-intermediate, large group)

Learners must be seated in organized rows at least 4x4. Have the front row of

learners stand. Ask simple questions like "What day/time is it?" Learners raise their

hands (or blurt out answers) and the first person to answer correctly may sit down.

The last standing learner's line (front-to-back) must stand and the game continues

until 3-4 rows/lines have played. You can use diagonal rows if the same person

gets stuck standing each time. To end, ask a really simple question (e.g. "What's

your name?") directly to the last student standing. Variation for small group: the

whole group stands and may sit one by one as they raise their hands and answer

questions.

Show & Tell (any level, individual or group)

A learner brings an item from home and talks about it in front of the group. Give

learners enough advance notice to prepare and remind them again before their

turn. Have a back up plan in case the learner forgets to bring an item. Beginners

may only be able to share the name of an item and where they got it. Be sure to

give beginners specific instructions about what information you want them to tell.

Sing a Song (intermediate-advanced, group)

If you're musically inclined, or even if you're not, songs can be a lively way to get

everyone involved.

Mystery Object (advanced, group)

Bring an item that is so unusual that the learners are not likely to recognize what

it is. Spend some time eliciting basic descriptions of the item and guesses about

what it is and how it's used. If possible, pass the item around. This is an activity in

observation and inference, so don't answer questions. Just write down descriptions

and guesses until someone figures it out or you reveal the mystery.

Ice Breakers

Name Bingo (beginner, large group)

Hand out a blank grid with enough squares for the number of people in your class.

The grid should have the same number of squares across and down. Give the

students a few minutes to circulate through the class and get everyone's name

written on a square. Depending on the number of blank squares left over, you can

have them write their own name on a square, or your name, or give them one 'free'

square. When everyone is seated again, have each person give a short selfintroduction. You can draw names randomly or go in seating order. With each

introduction, that student's name square may be marked on everyone's grid, as in

Bingo. Give a prize to the first 2-3 students to cross off a row.

Name Crossword (any level, group)

Write your name across or down on the board being sure not to crowd the letters.

Students take turns coming to the board, saying their name, and writing it across

or down, overlapping one letter that is already on the board. It's usually best if you

allow students to volunteer to come up rather than calling on them in case a letter

in their name isn't on the board yet, although the last few students may need

encouragement if they're shy.

Similarities (beginner-intermediate, group)

Give each person one or more colored shapes cut from construction paper. They

need to find another person with a similar color, shape, or number of shapes and

form pairs. Then they interview each other to find 1-2 similarities they have, such

as working on a farm or having two children or being from Asia. They can share

their findings with the class if there is time.

Pair Interviews (intermediate-advanced, group)

Pairs interview each other, using specified questions for intermediates and open

format for advanced students. Then they take turns introducing their partner to

the whole class. Be sensitive to privacy when asking for personal information.

Snowball Fight (any literate level, group)

Give learners a piece of white paper and ask them to write down their name,

country of origin, and some trivial fact of your choice (such as a favorite fruit).

Have everyone wad the pages into 'snowballs' and toss them around for a few

minutes. On your signal, everyone should unwrap a snowball, find the person who

wrote it, and ask 1-2 more trivial facts. Write the questions on the board so the

students can refer to them. Remember that each learner will need to ask one

person the questions and be asked questions by a third person, so leave enough

time. Variation for small groups: learners can take turns introducing the person

they interviewed.

Mystery Identities (any literate level, group)

Write the names of famous people or places (or use animals or fruits for a

simplified version) onto 3x5 cards. Attach a card to each learner's back. Give them

time to mingle and ask each other questions to try to figure out their tagged

identities. This is usually limited to yes/no questions, although beginners might be

allowed to ask any question they can. Be at least 90% sure that the learners have

heard of the items on the cards and especially the ones you place on their own

backs.

ESL Games

Some of these can be used as warm-ups. Most of them can be linked to any lesson theme

or grammatical form you're working on. These games usually require at least a small

group to play, but you may be able to adapt some of them for one-on-one settings.

Find Someone Who... (literate beginner-intermediate, group)

Create a list of characteristics such as "likes chocolate," "has two children," or "can

swim." There should be 10-15 items, and you can relate them to your lesson if you

wish. Then let the learners mingle and get signatures of other learners who fit the

descriptions. Make sure they are using appropriate question forms ("likes X"

becomes "Do you like X?") and aren't just pointing to the items on the page. This

can be made into a Bingo activity by putting the items on a grid.

Pictionary (any level, group)

Divide into 2-3 teams and give each a supply of paper if you aren't using a

whiteboard. It's best if each team can sit around a table or have their own

whiteboard space. Tell one member from each team what item to draw, and on

your signal they may begin. The first team to guess wins a point. Play a fixed

number of rounds and the team with the highest score wins. Notice that in this

version, all teams are working independently at the same time to guess the same

word, but you could take turns with each team. You can also give stickers or

wrapped candy to the person or team guessing correctly if you don't want to make

it competitive with points.

Scavenger Hunt (any literate level, group)

Divide into teams and hand out a list of items to be collected (a penny, a stick of

gum, a signature, a pine cone, a shoelace, be creative). Define the searching

range (classroom, house, campus, neighborhood, building). The first team to

return with all the items wins a prize.

Twenty Questions (intermediate-advanced, individual or group)

Select an object in your mind and let the learners ask up to twenty questions to

guess what it is. Trade places with the winner and let that learner select an object

for the next round.

Storyline (intermediate-advanced, group)

Divide into groups of 4-6 people. Give everyone a sheet of paper and ask them to

write the first sentence of a story at the top of the page. It may begin "Once upon

a time..." if they like. Then they pass the page along to the next person in the

group. That person reads the first sentence and adds one more to it to continue

the story. Then that person folds the top of the page backwards so only his or her

own single sentence is visible and passes the page to the next person. That person

writes one more sentence, folds the paper back to hide the previous sentence, and

passes it along again. When the pages have passed through the entire group one or

two rounds, everyone unfolds the pages and reads the stories. They are often

hilarious, and this game usually generates contagious laughter.

Telephone (any level, group)

Divide the group into two teams and have them stand in single file lines. Whisper a

somewhat complex sentence (according to their level) into the ear of the first

person in each line. Make sure no one else hears. Give the same sentence to each

line. Then each person must whisper it into the ear of the next person until the

end of the line. The last person must either say the sentence or write it on a

whiteboard. The team whose final sentence most resembles the original one wins.

In case of a tie, the fastest team wins. Try giving an easy sentence to start with to

build confidence before moving onto a difficult one. If the game is too hard in the

first round, learners will decide it's no fun.

Miscellaneous Activities

These activities generally require more preparation than warm-ups and games, but they

will also take more class time and can be used to practice whatever material you're

teaching. As always, be creative and adapt them to your needs.

Pre-Written Dialogs (any literate level, pairs)

Many textbooks include sample dialogs, or you may write your own. They can be

useful to break the ice with shy learners, but they are not truly communicative

because no original language is produced. Use them to practice self-confidence or

to illustrate a grammatical pattern. Make them more communicative by selectively

choosing words or phrases which can be blanked out and requiring students to

substitute their own ideas in the blanks. Beginners may need a list of options to

choose from. Having learners memorize the dialogs can help them gain the

confidence to try role plays.

Role Plays (intermediate-advanced, pairs)

Role plays are far more communicative than pre-written dialogs, but they are

often challenging for beginners or shy students because they must come up with

their own language to fit a particular situation. They may be too difficult for

beginners or shy learners. In its most difficult form, groups of 2-3 learners are

given a scenario and asked to act it out on the spot. To make a role-play less

intimidating, learners may be allowed 5-10 minutes to think it through first. You

may allow them to write down their scripts, which is often necessary at lower

levels. Writing also gives learners a chance to ask questions about the language

before they use it in front of their peers.

Information Gap (any level, pairs)

Each learner has limited information which the other needs. They must ask each

other questions to get the information. To be more communicative, the answers

should have some degree of ambiguity that needs to be cleared up with more

questions. For example, both learners receive a drawing of a group of people. Each

has the names of half of the people labeled on the picture, and the rest of the

names in a list. They describe their pictures and ask questions to match names

with the unknown people. "Is Sally holding a coffee cup?" may need to be followed

by "Is she tall or short?" if there are two women holding coffee cups. Information

gaps can be done with street maps, telling time, daily schedule, job interview,

spelling, etc. Look for those that encourage interactive questioning rather than

mere reporting of easy information. Make sure the students don't show each other

their worksheets to give away the answers.

Sequencing (any level, pair or group)

In sequencing activities, students must put jumbled pieces of information into a

logical order. Unlike jigsaw activities, all students in the group are allowed to see

all the pieces of information. They work together to understand each piece and

decide where it fits among the rest. Examples include months of the year, strip

stories where a story is cut into separate sentences or paragraphs (use pictures for

non-literate students), or instructions (recipe, craft, etc.) cut up by lines. It's fine

to have more information pieces than group members.

Q & A Matching (literate beginner-intermediate, large group)

You need to have an even number of participants, so you may need to join in

yourself. Get enough 3x5 cards so that you have one per person. On half of the

cards write questions, and on the other half write appropriate responses. Use

language your learners know and avoid new vocabulary. Examples could be, "What

month is it? / It's July." or "Where did you go yesterday? / I went to City Park." Mix

up the cards and hand one to each student. Let everyone stand up and mingle. The

students with questions should read their questions aloud and those with answers

should read their responses. Make sure they don't show each other their cards.

When students think they have a matching pair, they can sit down. The activity

will go faster if the question cards are a different color than the answer cards.

Watch out for questions that could use more than one of your answers, or answers

that could be given for more than one of your questions. This will result in an odd

pair left over if students don't match your original question and answer correctly.

For multilevel groups, make some questions/answers harder and give these to the

higher level students. At the end, have all pairs read their questions and answers

to check them.

Fill-In-The-Blank (any literate level, individual or group)

Prepare a worksheet containing a text or song lyrics with key words blanked out.

For beginners you can blank out alphabet letters and not whole words, choosing

distinct sounds rather than silent letters. Then read the text or play the song and

let the learners fill in the blanks. You may need to repeat it 2-3 times. Then go

through the text (have learners take turns reading their answers) to check it. Ask

learners to spell the difficult words. You can focus this activity by choosing a

certain type of word to blank out (such as articles or "be" verbs) or just choose

random words. Be aware, though, that if you choose a lot of long words close to

each other the learners may have trouble keeping up with listening as they write.

This is also called a cloze exercise.

Problem-Solving (intermediate-advanced, group)

This works best with small groups. Present a problem (a scenario, possibly) and

give groups some time to discuss the best approaches or solutions and come to

agreement on a course of action. The problem should require a decision with pros

and cons and necessitate creative collaborative effort. It can be something like

deciding upon seven items to take along for a week in the wilderness, or choosing

between living in a 5-bedroom house in the city or a 1-bedroom cottage by a

mountain stream. Press learners to explain why they chose their answers.

Reading: Oral vs. Silent (any literate level, individual)

The skills used in oral reading are different from those used when reading silently.

Use oral reading sparingly to work on verbal presentation (pronunciation,

intonation) and be sure to allow time for silent reading. It's best to set a time limit

so the learners know just how much time they have, and you can flex it if your

estimate is off. When they read silently, learners will be able to absorb meaning

and look at English usage much more fully than when they read aloud. They will

also be able to tackle longer passages.

Freewriting (any literate level, individual)

Give learners 5 minutes to just write their thoughts. You may guide them by

providing a question or topic (beginners will probably need guidance), or give them

complete freedom. Make sure they just write without worrying about errors. The

idea is to get thoughts onto paper with whatever English is available. This can be a

warm-up for a more formal writing assignment or just a jump start for thinking in

English.

Short Composition (any literate level, individual)

Unlike freewriting, learners need to edit their work. You should provide a topic or

visual stimulus (full page magazine pictures work well) and circulate among the

students as they write. By allowing time to write during the lesson (as opposed to

homework) you give them a chance to ask you questions and refine their work. You

can also have learners pair up to read each other's work and make suggestions. At

the end, ask learners to volunteer to read their compositions to the group, but be

careful about requiring everyone to share. You can customize your topic to

practice specific English forms. For example, ask past/future questions to work on

verb forms, or practice prepositions by showing a picture of a room and asking

learners to describe the locations of all the objects they can identify. You may also

ask advanced learners to summarize and respond to a brief reading passage.

Flash Cards (any level, individual or group)

Flash cards can be used for simple vocabulary drills, numbers, or memory games.

Avoid using cards that translate a native language word into English. Rather,

choose or make cards that use pictures or symbols to prompt English answers. Of

course this isn't an issue if you're using numbers. Try including mathematical

equations, too, or time-telling clocks.

Dictation (any literate level, individual or group)

Say a sentence at natural speed and ask learners to write down what you said.

You'll probably need to repeat several times. Don't slow down your speed unless it's

absolutely necessary. Then ask a learner to read the sentence to check it. Finally,

write it for all to see (or ask an advanced student to write it) and then say it again

a few times at natural speed. For a twist, ask a learner to dictate a sentence for

the rest of the group. Learners will be thrilled if their teacher (you) can correctly