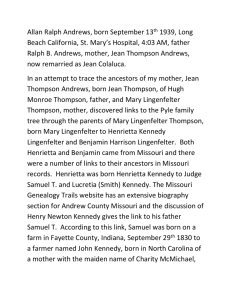

Allan Ralph Andrews, born September 13th 1939, Long Beach

advertisement