File

advertisement

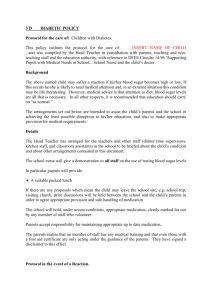

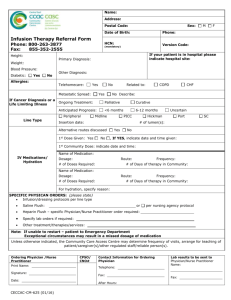

Children’s Hospital Children’s Hospital Amanda M. Scott National University HTM 680 Professor Robert Kaye January 2014 Children’s Hospital Many unfortunate events have occurred in hospital settings over the years. Whether it is a near miss, patient safety event, or a sentinel event there is always something to be learned from the event to improve processes. In the case of Matthew from Children’s Hospital and Clinics in Minneapolis, MN, this was a medication error that could have been prevented (Edmonson, Michael, & Tucker, 2007). Due to multiple factors, Matthew was accidently given an overdose of intravenous morphine, which resulted in the patient needing to be resuscitated. Thankfully the resuscitative efforts were successful and Matthew recovered. This became a learning experience not only for those directly involved but for all in medicine. Throughout the risk assessment process specific risks were identified and further mitigation strategies were developed to assist in preventing this event from occurring again. There are two risks that were quite evident in this event. The first risk that needed to be addressed is training. Specifically training for the nursing staff and anyone involved in utilizing and administering medications via an electronic infusion pump. One of the commendable attributes to this situation is that the nurse on orientation did ask for help regarding the pump, as he was unsure. Unfortunately it was more of a case of the blind leading the blind. It was found that many of the nurses on this unit were unfamiliar with this specific electronic infusion pump because most of their patients do not require continuous intravenous pain management. Secondly, it was noted that the nurse on orientation was used as a second verifier prior to starting the infusion pump. This should never be the case. Anyone on orientation should not be allowed to verify medications. This should always be between two licensed providers NOT on orientation. At least this has always been the standard. Children’s Hospital The likelihood of the training risk is medium to high. I believe there is a range with this risk as it will not always cause or result in harm. In Matthew’s event, it caused great harm and nearly killed him. Training is such a broad term but is very important to remain safe. The other risk noted was the labeling of the actually medication. The nurses agreed, after the fact, that the labeling was confusing, at least the part of the label that was shown. The location of the label and the documentation on the label need to be clear and concise. This also rolls into training as well. The nurses should have clarified the medication prior to even taking the medication to the bedside. The likelihood of the labeling risk is high. Granted, not every medication if given too fast or too much dosage will do harm, the severity of those mediations that can cause harm make this a high risk. There have been many situations where I have had to clarify medication dosage with another nurse and even providers. When I worked in the Intensive Care Unit and on Labor and Delivery we even had cheat sheets for certain medications that we required during resuscitation. This did not mean that we skipped any steps or verifying the medication with another provider. This is just an example of how, even if labeled correctly, some medication dosages can be tricky. The Children’s Hospital did follow up the even with a collective collaboration of all involved as well as leaders. This occurred to help understand what caused the event and how to prevent this from happening again. I truly enjoyed reading that Dr. Robinson stressed this focused event analysis would be “a blameless environment” (Edmonson, Michael, & Tucker, 2007). In a culture of safety this is paramount. I have found in personal experience that this isn’t always the case. Children’s Hospital The risk mitigation strategies developed include risk planning and limitation as well as research and acknowledgement (Stoneburner, Goguen, & Feringa, 2002). Risk planning would involve future training for staff members. In this case, have all staff members utilizing the electronic infusion pumps; participate in hands on training with a super user. Create real life scenarios and have the staff members walk through how to set up and administer the medication step by step. Provide quarterly or bi-yearly proficiencies and keep track of all staff members training. Risk limitation would be to set safe guards or limits on the electronic infusion pump’s system. For example, morphine could be a preset medication with known dosages and if the nurse types in a dosage that is not typically prescribed, the pump will provide a warning. Pumps may also be programmed to provide an alarm setting for pediatric versus adult dosages for medications. Working on the “front lines”, I have used pumps that have similar settings. I thought it was a great safety feature especially if it had the medication I was going to administer. This allowed the pump to save the medication history as well as provide for safety alerts. I could also, easily look at that pump and know what exactly was running through it. In the Intensive Care Unit there were many times were I was responsible for more than eight intravenous drips one just one patient. It is extremely important to stay organized and have clear concise information. I particularly like research and acknowledgement as part of the mitigation process. Utilizing not only past research but also acknowledging current mistakes and learning from them will only make medicine safer and more efficient. The Children’s Hospital learned that they required further training regarding the pumps and needed to Children’s Hospital change the medication labeling. Acknowledgment of a wrongdoing may be difficult but it will only allow for growth. Matthew’s situation is a perfect example of where the five rights would or could have prevented a harmful situation. The five rights include the right patient, right medication, right dosage, right route, and right time. If the nurse’s had gone through the five rights they should have stopped at the right dosage. If they had recognized that the dosage on the label was difficult to understand they could have clarified with the pharmacy and provider prior to even bring the medication to the bedside. There has been many times during my career that I have easily verified a medication three or four times prior to even stepping foot into the patients room. Also, if the medication was verified with another nurse who was not on orientation, the dosage on the pump may have been caught. In this situation Matthew is a pediatric patient. Medication dosages for pediatrics are very different from adults. Many of the pediatric medication dosages are based off of the child’s most recent weight. As we are in the United States we tend to measure weight in pounds. However, when it comes to medication dosing, the pounds need to be converted to kilograms. The mediation itself may need to be converted from grams to milligrams or liters to millimeters. As you can see this requires a lot of math and precise math at that. This is another reason/example why having two licensed verifiers is required for safety of the patient. Pediatric patients are typically smaller in weight than adults are more sensitive to medications, hence why weight dosing is so important. The medication error that occurred to Matthew is not any single individual’s fault. Collectively as a team of medicine, all involved had some responsibility. The positive Children’s Hospital perspective is that the individuals involved, the facility, and any other medical facility can learn from this situation. It takes a team effort to provide safe and effective medicine. Julie Morath explained it simply, “the health system produces health, but it also produces harm.” (Edmonson, Michael, & Tucker, 2007). Acknowledging this will allow for further growth and improvement towards safer care. Children’s Hospital References Edmondson, A., Roberto, M., & Tucker, A.. (2007) "Children's Hospital and Clinics (A)." Harvard Business School 9(2) 1-25. Harvard Business School. Web. 1 Jan. 2014. Stoneburner, G., Goguen, A., & Feringa, A.. (2002) "Computer Security." National Institue of Standards and Technology 30, 1-40.