Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

advertisement

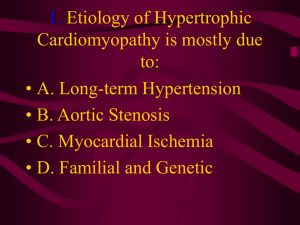

Running Head: HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY, THE SILENT KILLER Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, The Silent Killer Stefanie Varno Concordia University 23 August 2013 1 Running Head: HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY, THE SILENT KILLER 2 Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), which is classified as a rare disease by the Office of Rare Diseases of the National Institute of Health (NIH), causes atypical enlargement of the muscle of the heart (Right Diagnosis, 2011 & Mayo Clinic, 2013). The thickening of the heart muscle can cause great stress because it can make it difficult to not only pump blood out of the heart but also to allow oxygenated blood to refill the heart chambers (Medline Plus, 2013). HCM is an inherited condition and can affect anyone (Medline Plus, 2013). HCM frequently goes undiagnosed since there are few symptoms, and none that easily distinguish between HCM and any other cardiovascular disease (Mayo Clinic, 2013). If symptoms do occur they commonly include chest pain, dizziness, fainting, especially during exercise, fatigue, light-headedness, heart palpitations, shortness of breath and arrhythmias (Medline Plus, 2013). Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy is caused by a mutation in the genes. Not only does this mutation cause the heart muscle to grow unusually thick it can also cause the muscle fibers to grow in an atypical arrangement known as myofiber disarray (Mayo Clinic, 2013). These disorganized fibers then have the potential to lead to an irregular heartbeat known as arrhythmia. People can have different causes and types of HCM. Most individuals with HCM have HCM with obstruction meaning the septum in the ventricles is thickened (Mayo Clinic, 2013). This thickening causes the heart to work harder to pump less blood. There is also a nonobstructive HCM, which is when the muscle of the left ventricle becomes very stiff and decreases the amount of blood that can be held; meaning less blood is being pumped out with each contraction (Mayo Clinic, 2013). The severity of this disease varies from person to person; some people can live without suffering any adverse reactions while others may die from their condition. Running Head: HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY, THE SILENT KILLER 3 HCM is typically inherited and it does not discriminate, it affects men and women alike. It is the most common cardiac genetic disorder (Beutler and deWeber, 2009). The prevalence of HCM is approximately one out of every 500 people or 0.2% of the population (American Heart Association, 2013). This is equivalent to 544,000 people in the United States (Right Diagnosis, 2011). This is a dramatic increase from the believed prevalence of <1 in 100,000 in the 1980’s (Buetler and deWeber, 2009). Relatives of someone with HCM are at greater risk and should follow proper screening protocols to facilitate early detection. Children of those with HCM have a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation that causes the disorder (Mayo Clinic, 2013). A dreaded risk for some of these individuals is sudden cardiac death (SDC). In regards to the survival rate of HCM, two to three percent die each year due to SCD and over ten years the risk of death increases to 20% or more (Right Diagnosis, 2011). Although deaths are rare, HCM is the leading cause of heart related sudden death in people under 30 (Mayo Clinic, 2013). HCM is also considered to be the most common cause of exercise related sudden death in young athletes (Basavarajaiah et. al., 2008). “HCM has been positively identified in well over a third of cases (36%) of SCD in athletes under the age of 30, and cited as a possible cause in another 8%” (Buetler and deWeber, 2009). According to the NCAA each year nearly twelve collegiate athletes in the United States have a fatal ending due to cardiac arrest (Medcalf, 2012). “Sometimes the first indication of a problem is also the last” (Medcalf, 2012). It is a hard pill to swallow that with today’s medical capabilities, the young age of the individuals and their apparent good health, there is a disease that can end their careers and their lives instantly. Fred Hoiberg, a shooting guard for the Minnesota Timberwolves, was diagnosed with a hidden heart condition like Running Head: HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY, THE SILENT KILLER 4 HCM to which he refers to as “playing with a ticking time bomb in my chest” (Medcalf, 2012). Even though HCM may show no symptoms it can change the life of its victims when it is discovered, like in Hoibergs case, once his cardiac ailment was found he was no longer allowed to play basketball even though he felt as healthy as ever. Figure 1. Causes of sudden cardiac death in young competitive athletes. (Atkins, et. al., 1996) Running Head: HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY, THE SILENT KILLER 5 A huge problem with HCM is that it is not screened for in routine sports physicals. It is an unpredictable ailment and can be easily hidden for a long time. “Diagnosis is difficult, and predicting which patients will develop severe complications and face the greatest risk of premature SCD remains an inexact science” (Buetler and deWeber, 2009). Currently the NCAA is conducting a study to see if there is a practical and cost-effective way to reduce the number of incidents of sudden cardiac death in collegiate athletes (Medcalf, 2012). Dr. Jonathon Drezner, President of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine and chief researcher of the NCAA funded study says that even with the implementation of a screening tool, there would still be room for error, no program can be perfect. The key to diagnosing HCM is the screening tool used. In the typical preparticipation sports physical the screening is very generic and is not set up to detect a condition such as HCM since it has few if any distinctive symptoms. Unfortunately young high school and college athletes are taken every year due to HCM. Only 20% of these individuals have symptoms of HCM and majority of them don’t report it because they either think it is normal or they are afraid of the consequences (Medcalf, 2012). One sign that could possibly be found during a routine physical is a heart murmur, but that is only in certain cases. If this is detected the athlete should be referred to his or he primary care physician (PCP) or a cardiologist for further testing. The test most commonly used to diagnose HCM is the echocardiogram (Echo). This test allows the doctor to see a picture of the heart to view the thickness of the cardiac muscle, the blood flow and the functionality of the valves (Mayo Clinic, 2013). Another key factor to look for is the pre-participation questionnaire. The questionnaire should ask several questions which could lead to referring the athlete for an echo. Those questions include: Running Head: HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY, THE SILENT KILLER 6 1. Have you ever passed out or nearly passed out during exercise? 2. Have you ever passed out or nearly passed out after exercise? 3. Have you ever had discomfort, pain, or pressure in your chest during exercise? 4. Does your heart race or skip beats during exercise? 5. Has a doctor ever told you that you have a heart murmur? 6. Has a doctor ever ordered a test for your heart (i.e. EKG, Echo)? 7. Has anyone in your family died for no apparent reason? 8. Does anyone in your family have a heart problem? 9. Has any member of your family or relative died of heart problems or of sudden death before age 50? According to Buetler and deWeber (2009), who listed these 9 questions from the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Acadamey of Family Physicans and other major organizations, only 17% of high schools in America ask all of these questions in there preparticipation physical screening. There is a debate as to whether all athletes should also have to undergo an electrocardiogram (EKG) during the pre-participation physical as well. Some obvious barriers include time and money. The EKG can help detect abnormalities with the heart but is not a certain detector for HCM. Italy utilized a 12-lead EKG as an additional screening measure for all high school athletes during their physical and has seen a 90% reduction is sudden cardiac death in young athletes (Buetler and deWeber, 2009). There are many different factors to consider when viewing these results and considering whether this should be the standard in the United States. Those include not just the time and money but Running Head: HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY, THE SILENT KILLER 7 the differences in the populations, the number of athletes, the need for trained professionals to perform and interpret the results and the number and effect of false positive tests (Buetler and deWeber, 2009). Individuals with HCM can go on to lead normal lives given the proper diagnosis and treatment early on. Education is key for these patients. Restriction from competitive sport is common and the insertion of a defibrillator to shock the heart if arrhythmia occurs is also a preventative measure. High school and collegiate athletes who die of SCD are difficult to deal with due to the appearance of health, anything we can do to prevent these deaths in the future should be considered. Running Head: HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY, THE SILENT KILLER 8 References American Heart Association (2013). Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Retrieved from http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/More/Cardiomyopathy/Hypertroph ic-Cardiomyopathy_UCM_444317_Article.jsp Atkins, Dianne L., Clark, Luther T., Crawford, Michael H., Douglas, Pamela S., Driscoll, David J., Epstein, Andrew E., Maron, Barry J., McGrew, Christopher A., Mitten, Matthew J., Puffer, James C., Strong, William B. and Thompson, Paul D. (1996). Cardiovascular Preparticipation Screening of Competitive Athletes. Circulation 94 (4), 850-856. Doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.94.4.850. Retrieved from http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/94/4/850.full Basavarajaiah, Sandeep, McKenna, William, Shah, Ajay, Sharma, Sanjay, Wilson, Matthew and Whyte, Gregory. (2008). Prevalence of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in highly Trained Athletes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 51(10), 1033-1039. Doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.055. Retrieved from http://content.onlinejacc.org/article.aspx?articleid=1138778 Beutler, Anthony and deWeber, Kevin (2009). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Ask athletes these 9 questions. The Journal of Family Practice, 58 (11), 576-584. Retrieved from http://www.jfponline.com/index.php?id=22143&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=174766 Mayo Clinic, 2013. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/hypertrophic-cardiomyopathy/DS00948 Medcalf, Myron, 2012. ESPN Men’s Basketball. Taking a Closer Look at Heart Issues. Retrieved from http://espn.go.com/mens-collegebasketball/story/_/id/8313100/when-hearts-young-athletes-fail-college-basketball Running Head: HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY, THE SILENT KILLER Medline Plus, 2013. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Retrieved from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000192.htm Right Diagnosis (2011). Statistics about Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Retrieved from http://www.rightdiagnosis.com/h/hypertrophic_cardiomyopathy/stats.htm 9