CPR for Veterinary Staff

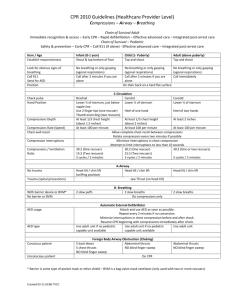

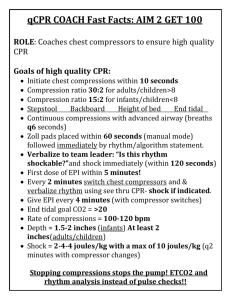

advertisement

CPR for Veterinary Staff Megan Brashear, BS, CVT, VTS (ECC) DoveLewis Emergency Animal Hospital The REassessment Campaign On VEterinary Resuscitation (RECOVER) Initiative was a collaborative effort of over 80 veterinarian specialists in Emergency and Critical Care. These specialists combed through both human and veterinary research to compose consensus-based clinical CPR guidelines. Their recommendations are included in this lecture. The most important aspect of any emergency is being prepared. Not only should your team have training but an area of the treatment floor should be designated to emergencies/CPR. A crash cart should be stocked and ready to go. In most cases a tackle box is appropriate and can be moved to the surgical suite or other areas of the hospital where it may be needed. The crash cart should be checked daily and kept stocked at all times. The emergency area should also have quick access to oxygen - either an anesthesia machine or oxygen regulator. Running drills with your team will help the staff feel comfortable in their roles and improve communication. The key to any crash kit is ACTION above THINKING. Your crash kit should be organized and pared down so that each area is not so overwhelming for use during an emergency. It is also very important to prepare owners for a possible CPR event. While it rarely happens, patients can arrest under anesthesia and the staff needs to know the owner’s wishes before proceeding with CPR. Make sure to discuss options with owners (basic CPR vs. open chest CPR vs. DNR) who leave their pets at the hospital for any reason. Label the patients so it is easy for the staff to identify owner wishes and makes sure to have phone numbers readily available. In cases of illness, there are warning signs to impending patient arrest. Trust your gut with these patients, you can ‘feel’ when something bad is about to happen and are ready to act. Changes in mentation or a persistently dull mentation should be closely monitored. Any change in respiratory pattern, rate, or depth is reason for concern; especially if it happens without any external stimulation (temperature being taken, recumbency changes, drugs administered). Any patient with weak or irregular pulses is at risk for arrest, especially if they started somewhat normal and are trending downwards. Hypotension also falls into this category – the body can compensate for a period of time but these patients need blood pressure support as soon as it can be given. Sudden tachy or bradycardia is immediate cause for concern – especially without external stimulation. Sudden tachycardia can be a sign of respiratory distress and/or pain – be sure to check for these conditions. Sudden bradycardia tends to continue to get worse so it needs to be treated ASAP. Any patient with respiratory distress is in danger of going into respiratory arrest and then CPA – keep a close eye on them and do what you can to provide oxygen supplementation and sedation. Severe hypothermia (especially in cats) can lead to arrest; these patients also must be monitored closely. Pay particular attention to patients that are slow to recover from anesthesia, check on them often and chart improvement. In ANY emergency it is important to take your own pulse first, take a deep breath and focus before proceeding. Triggers to start CPR in a patient include: Respiratory arrest – once an animal stops breathing full arrest isn’t far behind Agonal breathing patterns – while it may look like the patient is taking deep breaths this is the deepest part of their brain stem desperately trying to keep them alive – for all intents and purposes an agonal animal is dead. Non-ascultable heart beat – if you can’t hear it, it isn’t happening Non-palpable pulses – even in very sick patients there should be at least a faint femoral pulse. If there is still a heartbeat but no pulses the patient may not be in full arrest but is certainly on their way and needs intervention Ventricular fibrillation on ECG – these patients are no longer circulating blood and it is vital to treat this right away Chest compressions are the most important duty in CPR. They should be started as soon as arrest is recognized and continued throughout. These compressions are the only means for oxygen to be carried to the brain and every time compressions are stopped the brain is deprived of oxygen. When chest compressions are done correctly it is very tiring; compression efficacy decreases dramatically over time, so don’t be a hero. SWITCH OUT OF CHEST COMPRESSIONS EVERY TWO MINUTES. Chest compressions on cats are usually done with them in lateral recumbency. Cats have a flexible ribcage and should be relatively easy to compress. You want to compress their chest to 30% of its diameter and do 100 compressions a minute. Careful not to go too fast, you want to give the heart time to refill before compressing it again. Chest compressions on most dogs are performed in lateral recumbency. Small dogs: Very small dogs can be compressed similar to cats, but dogs have a stiffer ribcage and you will use the same technique as large dogs. Large dogs (Labs, Pit Bulls, Boxers, Shepherds, etc): Place your hands at the widest part of their chest. By compressing at the widest part of the chest, you are using their tissue and muscle mass to compress the heart (thoracic pump technique). Stand at the spine of the dog and place your hands on the widest part of the chest (halfway between sternum and spine – halfway between the shoulder and end of the ribs). Position your shoulders over your hands, (you need leverage, use a stepstool or kneel next to the dog on the table) lock your elbows, and bend at the waist with every compression using your body weight to compress the chest 30% of its diameter. You will need to do 100 compressions a minute. Everyone should be trained to do chest compressions so that you can trade out every two minutes. Keel chested dogs (sighthounds): Place your hands closer to their sternum, over their heart. Because of their conformation you can compress their heart and do not have to involve their entire chest. Place your hands over their heart, position your shoulders over your hands (you need leverage, use a stepstool or kneel down next to the dog on the table), lock your elbows, and bend at the waist using your body weight to compress the chest 30% of its diameter. You will need to do 100 compressions a minute. Everyone should be trained to do chest compressions so that you can trade out every two minutes. English bulldogs (large French bulldogs): Place the dog on its back. Place your hands at the center of the sternum, position your shoulders over your hands (you need leverage, use a stepstool or kneel down next to the dog on the table), lock your elbows, and bend at the waist using your body weight to compress the chest 30% of its diameter. You will need to do 100 compressions a minute. Everyone should be trained to do chest compressions so that you can trade out every two minutes. While compressions are started it is time to establish a patent airway. Obviously the quickest and most simple way to achieve this is through orotracheal intubation. Depending on the condition of the animal a tracheostomy may be necessary – be sure to know the supplies needed and what is involved with this procedure just in case. If possible, intubate the animal in lateral recumbency to allow for compressions to continue and maintain as much cerebral perfusion as possible. Once the patient is intubated you will need 100% oxygen ready – this can be achieved with an anesthesia machine or an ambu-bag hooked up to an oxygen line. It is a good idea to have some sort of suction available in case there is blood or fluid in the airway, and some gauze and forceps ready to clean out the oropharynx if necessary. Once the patient is intubated, it is very important to secure the endotracheal tube as soon as it is placed and to inflate the cuff. We need to be able to put pressure and hold pressure in the lungs during CPR and if the cuff is not inflated all of the air pressure will leak out of the lungs and your breaths will not be effective. Once the patient is intubated and hooked up to 100% oxygen it is time to breathe for them. Begin a rhythm of breathing at 10 breaths a minute. This seems abnormally slow, especially with all of the adrenaline happening. There are a couple of important reasons for this slow respiratory rate. When a patient experiences CPA the body hangs on to oxygen – it is not using and releasing C02 like normal. Also, every time you breathe for the patient it increases intrathoracic pressure which them decreases venous return and lowers cardiac output. The more they breathe the less your compressions are helping. Give them a breath every 6 seconds. If you are using an anesthesia machine be sure to keep an eye on the pressure gauge. In most CPR cases the pressure should go to at least 20cm/H20 with each breath, talk with the DVM about increasing or decreasing that pressure in the face of thoracic trauma. If you are using an ambu-bag pay attention to the compliance of the bag, if it is getting more difficult to squeeze the bag there may be a pneumothorax or other condition that needs to be addressed. IV access is an important part of circulation. Be careful not to assume that every patient undergoing CPR needs a bolus of crystalloid fluids. Fluid overload can overfill the heart and reduce cardiac output. Be sure to communicate with your DVM before starting a fluid bolus. The jugular route is the best route for fluids and drugs during a CPR situation. These medications have a direct line to the heart when given via the jugular route. However, this is often the most challenging route when chest compressions are being performed. If it is possible to place a jugular catheter without stopping compressions then by all means place one! Be sure to secure it well (suture!). Next best is a peripheral catheter. Hind legs are useless; the chances of drugs given through a saphenous catheter reaching the heart during CPR are slim to none. Use the cephalic veins and make sure to follow each drug with a 10-20ml bolus of saline or crystalloids and elevate the limb to let gravity help deliver the drugs. Drugs can also be given via the endotracheal tube if IV access is unsuccessful – the dose will need to be adjusted (usually double the dose) and suspended in sterile water. Attach the syringe to a red rubber catheter and feed it down the ET tube. Drugs are better absorbed endobronchial than via the trachea. There are a variety of drugs that are kept in crash carts for various emergency situations, the most important ones to use and be familiar with are epinephrine, atropine, and naloxone. Epinephrine: Given every 3-5 minutes Causes vasoconstriction increasing arterial pressure, improving perfusion to the brain 0.01mg/kg IV; 0.1mg/kg IT Watch for ventricular tachycardia post-arrest (side effect) Atropine: Use only if patient has a heartbeat Increases heart rate (intense vagal stimulation) 0.5ml/10# IV Naloxone: Reversal for opioids. Should be given in any anesthetic arrest. 0.1 mg/kg IV Anesthetic arrest can happen and it allows for the best chance to revive the patient if it is caught quickly enough. Use your monitors but don't rely solely on them. Use an esophageal stethoscope that will allow you to quickly determine patient decline vs. equipment malfunction. If your patient arrests under anesthesia, turn off the anesthetic gas first, disconnect and flush the line with 02, and begin breathing for the patient (10 breaths per minute). Alert the doctor doing surgery, they can start either external or internal compressions. Any drugs that can be reversed should be reversed, and resuscitation drugs given as ordered. Once you have started CPR it is important to evaluate your patient’s vital signs and watch for changes for better or worse. Use whatever monitors you can – the multiparameter monitors for anesthesia work great in these cases. This allows for watching the ECG, monitoring Sp02, ETC02, body temperature, etc. If you stop compressions to check for an ECG rhythm make sure to not stop for longer than 10 seconds. You can stop respirations for 20-30 seconds to see if they will breathe on their own. Teamwork is vital to a successful CPR. A team leader should be appointed and that leader will assign tasks to the rest of the team including chest compressions, ventilator, IV access, drug administrator, and a recorder. Communications should be clear and repeated back so that everyone is clear on who is doing what and mistakes are decreased. In many situations, a team member may be responsible for multiple duties and must communicate what they are doing. After any CPR situation, the team should gather for a debriefing to discuss what went well and what can be improved upon. Everyone on the team should be comfortable asking questions and a supportive environment fostered. Run drills with your team, and be sure to include all members of the team. Communication is important in a CPR situation so that everyone knows what everyone else is working on. While CPR in many situations may be unsuccessful, the training and practice is worth it for those that return home to their owners. References Available Upon Request