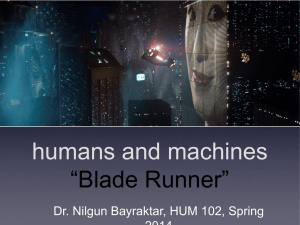

Our interest in the parallels between Frankenstein and Blade

advertisement

Our interest in the parallels between Frankenstein and Blade Runner is further enhanced by consideration of their marked differences in textual form. Evaluate this statement in the light of your comparative study of Frankenstein and Blade Runner. Sample response: Prose fiction and Film Prescribed texts: Frankenstein, Mary Shelley, 1819 Blade Runner (Director’s cut), Ridley Scott, 1982 Introduction sets out the main argument: that the texts share common content, but changes in context, audience and form mean that the content is handled differently There are many parallels between Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. They both explore major questions about the nature of being human, personal identity and whether or not people should “play god” by creating other life. They share the technique of interior narrative, so we understand what the major characters are thinking and what the motivations are for their actions. However, while the big questions about human nature may not have changed substantially since the early 19th century, the world is now a very different place and the textual forms clearly express that difference. Shelley’s Gothic novel becomes Scott’s film noir/crime fiction/sci-fi film, and the way the ideas are explored, and the audience for these ideas, are both very different. Frankenstein was published in 1819, when political upheaval in parts of Europe and major advances in science and medicine were challenging established ideas about people and society. The novel asks us to consider what it means to be a human being – can a human being be “made”, as the Creature is?; how is identity formed?; are scientific and medical advances incompatible with religious views?; what responsibilities do we owe to others? These are much the same questions that Scott asks in Blade Runner, although he does not address the conflict between science and religion in the same terms as Shelley. The interest in the texts lies in comparing how the same ideas are explored differently, through different mediums and for different audiences in different times and places. How Shelley treats the ‘man playing god’ concept The Christian understanding of God as the creator of all life underpins Shelley’s novel. Frankenstein is the anti-hero, whose acts of creation are so obscene and corrupt he must perform them alone and well out of sight. In true Gothic style, these unacceptable acts are performed in secret locations, rooms within rooms where decent people cannot find out what is going on. The secrecy, deception and Shelley’s language – “charnel-houses”, “decay and corruption” – tell us that Frankenstein’s actions are intrinsically wrong. His new-found knowledge of science and anatomy is disturbing and “astonishing”. He hesitates about what to do with it, not because he thinks that creating life is inherently wrong, but more because he wonders if “science and mechanics” are advanced enough to work. His qualms are all about the technical aspects, and not about the inherent morality. How the same concept is treated in film In Scott’s film we do not have such a specific view of the moral argument about creating life though there are religious allusions in the images of Roy’s death. Tyrell has been handsomely rewarded by society for creating replicants; this is a multi-cultural, postindustrial world where there are many beliefs and non-beliefs. Tyrell’s personal god, capital, is the dominant ideology, so what he does is a mark of success and does not need to be hidden away like Frankenstein’s work. Tyrell’s headquarters is a ziggurat, a temple to capitalism. However, Tyrell himself does hide away in this temple – he lives in as much of a Gothic cloister as Frankenstein, because the world he has helped to create is now so toxic he cannot venture out into it. He imagines he is safe from the monsters he has made, but Roy breaches his defences and has his revenge. Scott shows us that the seemingly-impregnable fortress can be breached, just as Shelley tells us that no matter how much Frankenstein hides away, he can’t hide from the Creature or from knowledge of what he has done. The search for identity in the Both texts consider how identity and a sense of self are shaped. In the novel, we learn that the Creature is self-taught. Rejected by his creator and by society, he must learn novel about people and the world from books. He remains unsatisfied, however, because he cannot form a meaningful relationship with anyone, and it is Frankenstein’s refusal to help him in this that tips him from the reasonable to the vengeful. We learn about the Creature’s development through his conversations with Frankenstein, told from his own personal perspective. In the novel, we are given the Creature’s perspective and Frankenstein’s perspective, both mediated through Captain Walton’s narration. The prose fiction form allows Shelley to develop her ideas at length and convey the inner feelings of the characters in some detail, as well as provide commentary on the action and morality via Walton. How identity is represented through image in the film Scott also deals with questions of the self, showing us the importance of identity to the replicants through images. These constitute their implanted memories and create the sense of self, in a much more personalised way than the Creature derives from books. The replicants know the importance of these images of memories – on the run, they still carry their photos with them. We are not specifically told by any external narration in the film – the audience must pick up the clues from the images presented. In both texts, the importance of these memories and relationships is conveyed quite differently. The Creature tells us in his narrative that he learns about himself and others through reading – all information is conveyed through words. In the film, the replicants say nothing about the photos, but the fact that they are always with them connotes their significance – we see that they are important. Rachael is the one who comments on the importance of memory in building identity. Her whole sense of self hinges on whether the childhood memories she has are real or implanted. We see that her memories are blurred, which is ambiguous – are they blurred because of the passing of time or because they are unstable and unreal? Setting and the relationship between internal and external worlds in both texts In response to their different audiences, the texts have some marked differences beyond the thematic similarities. In particular, Blade Runner comments on the external world in ways that Frankenstein does not. In the novel, setting is used to show how Frankenstein has distanced himself from the world. He rejects the ordinary, normal world that his friends and family live in and instead inhabits the remote and unusual places – the remote Alps, the northern wastes, his laboratory hide-away. In contrast, the everyday environment in 2019 in Blade Runner is so contaminated by human greed and stupidity that only those who cannot afford to escape it go into it. The film opens with scenes of ravaged, polluted Los Angeles, adding another dimension to the notion of people “playing god”. We see the dire effects when human beings believe that they can interfere with nature. At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, neither Shelley nor her audience knew about environmental degradation – her concerns were only with corruption of the soul. Scott shows in his film what damage can result, not just to people but to the environment, when science, technology and capitalism run unchecked. Different genres bring out different aspects of plot and theme Both texts share a similar idea about the created beings – in some sense they are dangerous and must be stopped. Shelley uses this idea to explore notions of right and wrong and consider Frankenstein’s moral failings, especially when contrasted with the Creature’s earnest attempts to understand life and morality. She poses the question, “Who is the monster?” Scott exploits this ambiguity about right and wrong using elements of film noir, where the “crimes” are political and environmental as well as the more typical law-based actions. As in Frankenstein, the heroes and villains are not always clearly identifiable. The darkness of film noir suits the ideas in the film: the moral ambiguity, the destructive abilities of human beings, the sense of lawlessness and chaos that characterises Los Angeles in 2019. Conclusion comments on the most marked While there is a great deal in common between the two texts, Frankenstein and Blade Runner, there are also marked differences. The difference of almost two centuries in the production means that similar ideas are dealt with in different ways, taking into account changes in context, audience knowledge and expectation and the textual forms. While similarities and differences both texts share some features of genre, such as narrative perspective, one is verbal and the other visual, requiring very different approaches to the same material.