Full Size - Saint

advertisement

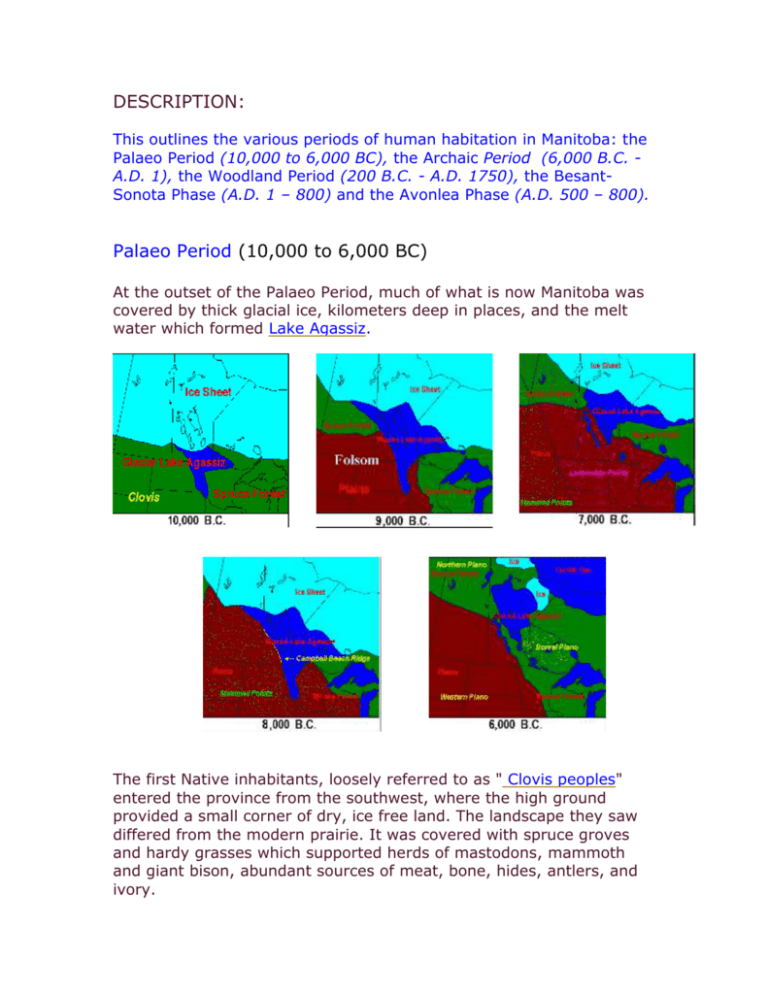

DESCRIPTION: This outlines the various periods of human habitation in Manitoba: the Palaeo Period (10,000 to 6,000 BC), the Archaic Period (6,000 B.C. A.D. 1), the Woodland Period (200 B.C. - A.D. 1750), the BesantSonota Phase (A.D. 1 – 800) and the Avonlea Phase (A.D. 500 – 800). Palaeo Period (10,000 to 6,000 BC) At the outset of the Palaeo Period, much of what is now Manitoba was covered by thick glacial ice, kilometers deep in places, and the melt water which formed Lake Agassiz. The first Native inhabitants, loosely referred to as " Clovis peoples" entered the province from the southwest, where the high ground provided a small corner of dry, ice free land. The landscape they saw differed from the modern prairie. It was covered with spruce groves and hardy grasses which supported herds of mastodons, mammoth and giant bison, abundant sources of meat, bone, hides, antlers, and ivory. A handful of spear heads provides the only evidence of this early human presence. During the following Folsom phase, Lake Agassiz began its gradual retreat, opening wider opportunities for settlement. Hunting groups migrated intonew territories and occupied many parts of province during Plano times at the end of the period. The Palaeo, or Palaeoindian, Period, is the earliest firmly established era of human activity in Manitoba. It began approximately 12,000 years ago, and some archaeologists attribute its development to the Aboriginal discoverers of North America, who migrated over the Bering land bridge that once connected Alaska and Siberia. Ways of life depended upon the hunting of now extinct giant mammals, such as the mammoth, that thrived in the Ice Age environments typical of the time. This emphasis earned Manitoba's First Peoples the title of "big game hunters". The Palaeo period in Manitoba can be subdivided into three successive traditions known as, Clovis, Folsom, and Plano, each of which is marked by new tool kits that were developed in response to changing environmental conditions. The Clovis and Folsom artifacts are sparsely distributed and confined to the southwestern part of the province. Evidence of Plano cultures is much more widespread and assumed the form of three regional variants, each of which was especially suited to exploit the particular food resources within the local environment. Installed 1990 Birds Hill Provincial Park Mammoths and mastodons were two of the most prominent species of megafauna ("big animals") to inhabit Manitoba during the last Ice Age. Between 65,000 and 25,000 years ago, mammoths grazed on the lush grasses of Manitoba's prairies, while mastodons browsed in the spruce swamps and woodlands. About 25,000 years ago, the climate cooled, massive glaciers advanced from the north, and the animals were forced out of Manitoba. The southwestern portion of the province was repopulated by mammoths when the glaciers retreated some 12,000 years later. By 10,000 years ago, the climate warmed to the point where the habitat changed. This, perhaps with centuries of hunting, brought about the animals' extinction. Mammoth and mastodon bones, teeth, and fragments of ivory tusks have been found in over a dozen locations in Manitoba, mostly in gravel quarries in the southern half of the province. A number of such finds have been made in the Birds Hill area. Clovis Traditions (10,000-9,000 B.C.) The Setting The first Manitobans were probably a Clovis group who followed migrating animal herds into the region during period of glacial retreat at the beginning of the end of the last great ice age. The earliest artifacts in Manitoba represent a well developed Native tool tradition and way of life known as Clovis that formed the first clearly established phase of the Palaeo Period. This culture was widely distributed throughout North America and is best indicated by the presence of the Clovis point, a spear head characterized by a fluted channel along its length. They faced a challenging climate of Arctic temperatures through much of the year and vast expanses of glacial ice and frigid water. However, these conditions were better than those which had prevailed in the previous centuries. The vegetation consisted of spruce forest inter-dispersed with tundra which it gradually replaced. This landscape was similar but not identical to the modern subarctic transition zone. The trees, shrubs, and grasses served as food sources for grazing and browsing mammals, including mammoth, mastodons, giant bison, horses, muskoxen, and caribou that could be hunted by early Native groups. Fossil evidence of the big game animals in Manitoba is not abundant, but isolated remains have been recovered. At Duck Mountain, Tyrrell (1892:130) may have found an entire mastodon skeleton and more modest finds of isolated mammoth and mastodon teeth or pieces of tusk have been recovered from the Swan River Valley, Birds Hill, Moosenose, Springfield and Dufresne. ( Pettipas 1970:10 ). As new land became free of ice and water, forest succession continued northward. The long term trend toward warmer and drier climates culminated in drought-like conditions which brought on the expansion of the central grasslands in the Late Palaeo Period. In the southwestern corner of the province, some habitable land had recently been freed from the ice. At the foot of the glacier, ponded meltwater formed Lake Agassiz which was eventually to occupy much of the province for many centuries. Eventually the land would rebound from the enormous pressures of ice and water to facilitate drainage and expand the presence of dry, habitable land throughout the province. Clovis and Folsom artifacts are represented in the form of their characteristic tools, stone spear heads marked by deep grooves along their length, a trait called a flute. These channels allowed the early hunters to haft the points to shafts to make formidable weapons for the pursuit of the giant beasts on whom they depended. Clovis bands were able to exploit the mammoth so successfully that they may have contributed to its extinction. Later, Folsom groups were able to cope with changes in environment by shifting to the hunting of the giant, long-horned bison that thrived on the grasslands after the mammoths disappeared. The Archaic Period 6,000 B.C. - A.D. 1 The Archaic Period marked the extensive development of new technologies and subsistence patterns in many parts of North America. It is divided into the Eastern Archaic Tradition and the Western Archaic or Desert Tradition, both of which had an influence on Manitoba. The driving force behind the transition from Palaeo to Archaic lifeways was most likely a change in climate, especially the ending of the Ice Age and a shift to much warmer and dryer conditions that marked the Atlantic episode, beginning approximately 8,000 B.C. Reduced supplies of water and vegetation as well as increasing pressure from highly effective hunting bands led to the disappearance as much as 95% of the North American big game species. To compensate for the disappearance of their traditional food sources, Native peoples invented new survival strategies and increased their exploitation of a broad variety of small mammals, waterfowl, fish, and plants. This new pattern has been called the "Broad Spectrum Revolution" and typifies not only the North American Archaic, but also the European Mesolithic and the African Later Stone Age, which represent similar responses to ecological changes that were occurring on a worldwide scale. Technologically, the Archaic is marked by the appearance of stemmed, notched or barbed broad bladed projectile points, considerably smaller than those of the Palaeo Period. They were crafted for use with an atlatl, or throwing stick, which came into wide use during the era. In many areas is it also marked by the appearance of ground stone tools, such as axes and milling stones, called manos and matates, These toolkits were probably developed to take advantage of the new resource base. The more intensive exploitation of local environments also simulated a change in settlement patterns towards greater sedentism, i.e. more prolonged use of individual living sites and in some cases permanent occupation ( Willey 1996). The increased localization and ecological specialization of the period supported a the development of several distinctive cultural traditions within and across major geographical zones. Archaic Dart Point Oxbow Type Atlatl The cultural phases and traditions within this period developed between 6,000 B.C. and A.D. 1, the earliest cultural evidence in the Manitoba region dating from 3,500 B.C. The relatively late Archaic settlement in the Province may be due to drought conditions across the Plains. Once the climate improved, populations increased substantially and for the first time extended into the Arctic zone along the Hudson Bay Coast. As elsewhere, the Archaic Period is marked in Manitoba by changes in climate, vegetation, food resources, and human activity. The climate was warmer and drier than Palaeo conditions. The last of the ice sheets melted and Lake Agassiz disappeared. Relieved from the pressures of ice and water, the land continued to rise and tilt, and Manitoba's current lake and river system took shape. Periodic occurrences of drought reduced water supplies, creating desert conditions in the central part of the province and expanding the bison grazing areas to the north and east. Modern bison (Bison bison) replaced the long horned Bison antiquus, probably because of the ability of the smaller animals to survive dry periods. Manitoba Native Peoples in Archaic times changed their food acquisition strategies to meet changing conditions. On the extensive grasslands they developed new hunting technologies and techniques to exploit the smaller but still formidable bison, which remained the mainstay of the economy until the 19th century. They also diversified their food resources to include deer, wolf, rabbit, fox, and wild plants such as gooseberries and cherries, a pattern that was repeated in other environmental zones in the province. Similar trends occurred on the tundra and in the boreal forests. Characteristic tools included small chipped stone projectile points and knives. Manos, matates and other ground stone tools associated with Archaic in other areas of North America have not been found in Manitoba sites. The Manitoba Archaic also provides the first direct evidence of many aspects of culture not yet well documented for local groups in previous times. Native peoples of the period interred their dead in formal burials repleat with grave goods, suggesting an elaborate belief system. Cultures of the Manitoba Archaic Period The Archaic Period in Manitoba is divided into Early Archaic, a time for which little evidence of extensive settlement, is available, and the Late Archaic, when Native groups migrated to every region of the province, populations increased substantially, and numerous traditions developed in response to increasing ecological and cultural diversity. Early Archaic: (6,000 - 3,500 B.C.) The Early Archaic is poorly represented in Manitoba, perhaps because of the drought conditions that were prevalent during the time. What little evidence has been uncovered has been located mainly in the river valleys of the Plains region. Limited remains of Logan Creek and Mummy Cave complexes indicate a movement into the province from the south and west. Small side notched atlatl points are typical of the traditions. Hunting of modern bison formed the dominant subsistence base, although increasing extensive use was made of a broad spectrum of animal and plant resources. Late Archaic (3,500 B.C. - 1 A.D.) In contrast to the previous period, the Late Archaic is well represented in Manitoba and was probably a time of substantial in-migration and population increase that occurred with an increase in precipitation. Numerous complexes developed in many parts of the province including: The Plains, represented by three distinct traditions, possibly indicative of an emerging cultural diversity: Late Plains Arachaic Point Styles Oxbow McKean The Boreal Forest, represented by The Shield Archaic The Old Copper Culture Pelican Lake Although not formally included in the Archaic, the Subarctic and Arctic zones underwent similar types of transformations in the course of development of the PreDorset phase, also known as the Arctic Small Tools Tradition. Around two thousand years ago the Archaic Period gave way to a new era of major technological and cultural development, known as the Woodland Period. The Woodland Period 200 B.C. - A.D. 1750 The term "Woodland" has been coined to label the late archaeological cultures developed by Native North American peoples throughout the eastern and mid-western parts of the continent. It is named after the Eastern Woodland environmental zone in which it first developed and is characterized by • pottery manufacture, • the construction of elaborate burial mounds, • the use of the bow and arrow. • cultivation of maize and other crops. In many parts of the world, these traits indicate a major transition in subsistence and settlement involving the growth of an agricultural village way of life known in Europe, Asia, and Africa as the Neolithic. The North American Woodland is distinct, however, in that Native peoples of this period retained a significant dependence on hunting and gathering and carried out regular nomadic movements. In some regions, particularly on the northern and western fringes, this basic pattern remained in place until the time of European contact. In the Mississippi Valley, it gave way the development of a fully sedentary way of life termed Mississippian that includes the magnificent architectural remains and art work of the TempleMound builders. On the American Plains a similar trend led to the appearance of Plains Village cultures. (You may be interested in visiting the CrowCreek Web site, a detailed exhibit on a 14th century Plains Village site in South Dakota) In the course of its development, the Woodland complex spread westward to many areas of the Plains resulting in the adoption of a seemingly contradictory term "Plains Woodland". In Manitoba the major elements of this tradition, especially pottery and burial mounds, were introduced throughout the forest and prairie regions just before the first millennium A.D. Maize was also grown on a limited scale, although hunting of bison remained dominant on the prairies, and mixed economies based on hunting, fishing, and wild rice gathering characterized the Boreal Forest subsistence regime. The expansion of these foraging economies were further enhanced by the introduction of the bow-andarrow. Although large agricultural settlements did not develop in the Province, Manitoba First Nations maintained important trading relationships and cultural exchanges with Plains Village and Mississippian groups to the south and east. A particularly interesting and crucial feature of the Woodland Period is the appearance of significant aesthetic and ceremonial artifacts evident in Native rock art. In Manitoba, this activity involved the elaborate arrangement of rocks into animal shapes and geometric patterns, technically termed petroforms, and the appearance of paintings, pictographs, and engravings, petroglyphs, on rock surfaces. Petroforms in the Shape of a Turtle and Snake Whiteshell Provincial Park Cultures of the Manitoba Woodland Period The Woodland Period is represented in the Plains and Forest regions of the Province. It can be divided into two sub-periods: 1. Initial Woodland: 200 B.C. - A.D. 800 and 2. Terminal Woodland: A.D. 800 - 1750. Initial Woodland (200 B.C. - A.D. 800). This period marks the introduction of many technological items and the development of new culture patterns. The use of the bow and arrow and clay pottery spread rapidly in many areas of the province. The arrowheads which tipped the shafts were much smaller than the darts and spearheads of previous time. The new weaponry meant that a variety of smaller mammals could be hunted and the range of the hunting grounds increased. The Plains people in the western region of the province continued to hunt bison using pounds and surrounds to capture the animals. Two early groups of people referred to as Besant and Sonota dominated the prairie landscape. The Richards Kill Site, a bison pound, and the Avery Site, a campsite, are examples of the Initial Woodland on the Plains. In southwestern Manitoba, the Avonlea culture reflected important contacts and influences from Sasketchwan and Alberta. Sonota Points In the Boreal Forest of the east and southeast section of Manitoba, Woodland people were hunting game, fishing and harvesting wild rice and a variety of nuts and berries. At the Wanipigow Site, carbonized wild rice and numerous other plant remains were excavated along with animal bones indicating a diverse and flexible use of resources. Local cultures of the period are characterized by a specific type of clay pottery known as Laurel, which is named after a town in Minnesota where the style was first discovered. Burial and ceremonial mounds are closely associated with this cultural group. Terminal Woodland (A.D. 800 - A.D. 1750) The final phases of the Woodland Period were marked by even more dramatic changes. Maize farming spread northwards into Manitoba. Small-scale gardening demanded a commitment from the people who planted the crops, to return at some point to tend the gardens and harvest them. The Lockport Site, on the east bank of the Red River at Lockport, Manitoba is the best example of local horticultural ways of life. Mound-building spread across the southern portion of the province. The most northerly example located to date is the Arden Mound near Neepawa, Manitoba. An interesting cultural group which had its roots in the Boreal Forest also used the resources of the Plains. The Blackduck culture produced a distinctive, highly decorative type of ceramic vessel, which may have originated in southern Ontario and northern Michigan or developed in northwestern Ontario out of the Laurel tradition. The ceramic style spread across the Lake Superior Basin and into parts of south and central Manitoba possibly in the course of the migration of the historic Ojibwe people. The Stott Site on the Assiniboine River near Brandon is an excellent example of these Boreal Forest migrants adapting to a Plains environment during this period. Northern Traditions. At the same time as Woodland complexes were spreading throughout the southern half of the province, the northern portion became settled by new cultural and linguistic families. At the end of the Archaic Period, the Pre-Dorset culture disappeared and was replaced by a new Arctic coastal people, the Dorset (ca 800 B.C. - A.D. 800). In Manitoba, the maritime economy of the Dorset people is represented only in the Churchill area and is considered to be short lived. The Taltheilei, the probable ancestors of today's Dene people, occupied a vast tract of land which stretched from the barren grounds far to the north in the Northwest Territories, to as far south as Southern Indian Lake . Their technology was quite different from the Woodland groups to the south, and no pottery has ever been found at any Taltheilei sites. The people followed the barren ground caribou migrations and supplemented the meat from the herds with fish. The End of an Era The Woodland Period represents the final era of Manitoba's precontact history. It ended in the 18th century with the coming of the fur traders, who opened the Postcontact Period and formed the first wave of European influence that was to eventually lead to the resettlement of Manitoba and the decline of a vital and fascinating way of life. Besant-Sonota Phase (A.D. 1 – 800) The Besant culture is the earliest representation of the Woodland tradition on the northern Plains. The Native peoples who developed it arrived in the Province approximately 2000 years ago and were the first inhabitants of the local prairie to use and manufacture ceramics. Like the other Plains peoples, Besant groups were heavily dependent upon bison hunting and were skilled in constructing jumps and pounds. They manufactured side-notched atlatl dart points using local stone as well as Knife River Flint and other materials imported from the south (Walde, Meyer and Unfreed 1995:18). Important sites that exemplify the phase include the Richard's Kill Site (Hlady 1967), where a depression on grasslands was used to confine bison for slaughter, and the Avery Site (Joyes 1969) in southern Manitoba, where evidence of meat processing was discovered. There is considerable debate about the relationship between Besant and the Sonota cultures. The pottery styles are quite similar although the elaborate burial customs of the Sonota, which included obsidian and pipestone offerings, are not found among the Besant remains. The classification of projectile points is also ambiguous. Hlady (1967) first reported the Richard's Kill Site as belonging to the Besant Phase and determined that the arrow heads as Besant as well. However, the elongated Knife River Flint points from the site have been reclassified as Sonota. Following Gregg (1994), we will treat Besant-Sonota as a combined category since they share stylistically diagnostic artifacts and occupy the same geographic region. Environmental Setting During the time that the Richard's Kill Site and the Avery Site were used by Besant-Sonota peoples, the climate was slightly wetter than present-day conditions. Like the earlier Archaic bison hunters, the Besant-Sonota movements on the Plains were dictated by the bison. The herds moved onto the open grasslands in the southwestern portion of Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan and Alberta during the late spring and early summer. In the fall, they took shelter in the wooded areas along the river valleys and at the edges of the grasslands (Morgan 1980). These areas were generally well watered, and supported a wider range of plant and animal resources than were available on the open grassland, making them attractive to human occupation. The Richard's Kill Site was located in a shallow slough or pothole on the prairie of southwestern Manitoba near Killarney. Sloughs, or swampy depressions such as those found at the Richard's Kill Site were ideal locations for trapping bison during a hunt. The animals became mired in the thick mud and were easily killed. The habitation area at the Avery Site was located on a terrace above the northeastern shore of Rock Lake. Here, the wooded slopes of the Pembina River Valley provided shelter from the open grasslands and alternative resources were available. Firewood, fish, deer, elk, bear and a wide range of plants, in addition to bison, were readily available. Subsistence and Technology In southwestern Manitoba just outside of Killarney, Mr. J. C. Richards and his family discovered over one hundred projectile points and several end scrapers on their farm property. Closer examination by archaeologist, Walter M. Hlady, in 1967, revealed that the location had been used by Besant-Sonota hunters as a bison pound kill site. The large size of the projectile points indicate the atlatl still served as the primary hunting weapon. Twenty-three large, side-notched Sonota and Besant points were recovered. The majority of the points from the site were manufactured from Knife River Flint. Besant Points Sonota Points The Richard's Kill Site represents only one component of BesantSonota life, bison pounding. Avery Site provides a more complex and complete picture which represents thousands of years habitation. The inhabitants used resources from the nearby lake and forest in addition to hunting bison. The many artifacts recovered indicate that the site was used for extended periods of time probably as a primary bison meat processing location. Evidence suggests that as many as 800 animals were butchered and dressed during a single habitation season from August - December. The absence of bison fetus or calf remains indicates that the site was not occupied during the spring. The bison bone remains are almost entirely smashed into splinters that measure not more than several inches in length. After the bone was broken, it was boiled so that the grease would float to the surface of the pot and could be collected to eat or to be used in making pemmican. Deer, antelope and rodent remains were also recovered (Joyes 1970:214). Besant pottery represents the earliest ceramic tradition on the Plains and is believed to have been introduced from the Missouri River in South Dakota. At the Avery Site, Besant clay pots were recovered in association with Besant-Sonota style projectile points. They were coarsely made and undecorated and assumed globular shapes with no necks (Joyes 1969:122-124). At least some of the Besant-Sonota pots or "Avery Corded Ware" were manufactured using cords of clay placed one on top of the other (Joyes 1969:124). The pots were used to cook food as indicated by the carbon found adhering to the interiors of the potsherds (Joyes 1969:123). Social and Economic Organization Woodland cultures such as Beasant-Sonota are known for their extensive exchange networks. The principal routes of long-distance trade were probably along the waterways. North-south trade occurred linking the Red River Valley to the Gulf of Mexico via the via the Mississippi River system. Besant-Sonota people were probably introduced to ceramic technology via these trading links. Trade goods located in Besant-Sonota sites include Knife River Flint from western North Dakota, copper from the Upper Great Lakes region, shell from the Illinois and Ohio rivers and Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic coasts (Gregg 1994:76). Avonlea Phase (A.D. 500 – 800) I go to kill the buffalo. The Great Spirit sent the buffalo. On hills, the plains and woods. So give me my bow; give me my bow; I go to kill the buffalo . Sioux Song (from Freedman 1988:50). For a limited time, another distinct Aboriginal Plains culture, Avonlea (A.D. 500-800), co-existed with Besant-Sonota on the prairies and reflected a similar subsistence strategy. Both peoples relied on the bison and used pounds and jumps. Besant-Sonota groups continued to use the atlatl for hunting, while the Avonlea utilized and developed the new bow and arrow technology. The finely crafted side-notched Avonlea points are much smaller and thinner than Besant or Sonota forms and represent a clearly distinct tradition. Avonlea people restricted their movements mainly to southern Saskatchewan, and Alberta. Their presence in Manitoba is concentrated primarily along the western edge of the province, where they are often found along with Beasant-Sonota tools. Environmental Setting Avonlea peoples inhabited the short grass prairie of south and central Saskatchewan, Alberta and western Manitoba. The Avonlea sites in Saskatchewan and Manitoba indicate a seasonal dependence on fish and small game as well as bison (Landals et al, 1995:18; Bryan 1991:121). The locations of many Avonlea sites in riverine environments and the lack of bison remains at some of these sites supports this hypothesis (Smith and Walker 1988). The arrival of the people who used the Avonlea tool kit is a source of some debate. Some archaeologists maintain that Avonlea points had their origins in the Mississippi Valley. Others believe that their pottery styles bear similarities to ceramics from the Eastern Woodlands of Manitoba and Minnesota (Nicholson 1987:43), suggesting migration from the east. Still another theory proposes that Avonlea projectile points developed from the earlier Pelican Lake style that was already present on the Canadian Plains, and that no movement of people occurred. Subsistence and Technology The small, thin, and delicately crafted projectile points that characterize the Avonlea phase are marked by by side notching and slight concavities at their bases. They have been recovered from only a few Manitoba sites: Moncur Farm, Avery, Miniota, Belleview Plateau, May Grompf, Stott, and the Pas Reserve. Archaeologists believe that these artifacts were the first arrowheads on the Canadian Plains. The use of bows and arrows replaced atlatls for bison hunting, since the arrows were smaller and lighter and therefore easier to carry and the bow allowed for a longer range and greater accuracy and velocity. The clay pots that are associated with Avenolea culture are of two types, globular and cone shaped. In Saskatchewan and Manitoba the cone shaped forms are the most common, while globular ones are found frequently in Alberta sites. Avonlea pots from Manitoba and Saskatchewan usually have a textured exterior surface which is likely the product of a woven or netted fabric impression applied to the damp, pliable clay during the manufacturing process. Punctates, spiral channels and smoothed outside walls were also used (Syms 1977, Bryne 1973). The partly reconstructed vessel recovered from the Miniota Site is believed to have been 39 cm high, conoidal in shape, and net-impressed with a double row of free-flowing rectangular punctates around the rim (Landals et al. 1995:11). Other artifact types associated with Avonlea include bone tools (Landals et al. 1995:15), end scrapers, wedges, and bifaces. Bison constituted the primary resource, although fish and small mammal were also exploited. The bison jumps and pounds that were constructed to facilitate hunting required considerable communal organization. At the "classic" Avonlea sites, such as Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump and Gull Lake, the cooperation of large groups of people was required to confine stampeding bison within constructed drive lanes. After the kill, the processing of bison products required intensive community work as the meat was butchered , smoked, and dried, and the heavy hides prepared for other uses such as tent coverings, clothing, and tools. The massive bone beds that characterize the Avonlea bison kill sites are highly visible due to natural erosion that has exposed the bones and the sheer numbers of animals slaughtered, a consequence of the efficiency of communal organization and the power of the bow and arrow. Settlement and Social Organization Little evidence of the types of shelters is found except for the numerous stone circles which dot the Plains. Coordinated bison drives suggest a high degree of cohesive community organization in which the members of several different bands may have participated. http://umanitoba.ca/faculties/arts/anthropology/manarchnet/chronology/archaic/