Overview of Ethical Systems

Overview of Ethical Systems

Normative Ethics: How ought we to act; provide a method or process for determining ethical behavior

1. Duty systems (deontological)

Motivation = Duty/do the right thing; an act in and of itself is right or wrong a. Natural law – Aquinas b. Divine right theory – Divine command theory holds that God’s commands are the source of ethics, that God is a moral authority and we ought always to obey his commands, irrespective of the consequences of doing so. c. Kant and categorical imperative -- One feature of Kantian ethics is its emphasis on reason. According to Kant, morality can be derived from rationality. Immorality is irrational. As rationality is universal, possessed by all human beings, morality is universal too; we are all subject to the moral law. Kant’s system of ethics attempts to derive the moral law from reason. Immorality, according to

Kant, involves inconsistency, and is therefore irrational. The first implication of Kant’s use of reason to ground morality is that it provides a response to the egoist. Egoism holds that we ought only to act in our own self-interest. Most philosophers reject egoism, but it is notoriously difficult to give an adequate justification for doing so. Kant’s theory provides such a justification: egoism is irrational, and so can be criticized on that ground.

The second implication of Kant’s use of reason to ground morality is that it explains the scope of morality. Rationality, for Kant, is definitive of human nature; it is universal among human beings. All human beings, then, because that have the capacity to be rational, ought to be moral. Other animals, lacking this rational capacity, are not subject to the moral law, and therefore cannot be judged by it.

Another aspect of Kant’s ethics is its lack of interest in motives. According to Kany, we ought to act from duty. Whether we want to do the right thing or not, we ought to do it; out motives are irrelevant to ethics. This means that someone who gives money to charity reluctantly, because they believe that they ought to, acts just as well as one who gives money to charity joyfully, because they have compassion for those less well off than themselves. In fact, the person that gives out of duty acts better than the person who acts out of inclination if the person who acts out of inclination would not have so acted absent that inclination. Intention refers to the intention to do one’s duty, not the intention to have a good outcome, as some of you have misunderstood it to be.

The central claim of deontologists is that certain types of act are intrinsically right or wrong, i.e. right or wrong in themselves, irrespective of their consequences.

This is in stark contrast to consequentialism, which holds that the moral status of an act is determined entirely by its consequences. Consequentialists hold that any act, even those acts that we would normally classify as morally wrong, is morally good if it has good consequences. In the view of the consequentialist, the end justified the means; it is morally permissible to use distasteful means (e.g. lying, stealing, physical violence, etc.) in order to achieve good ends (e.g. happiness, alleviation of suffering, etc.).

The deontologist is opposed to this approach; certain acts, the deontologist holds, should never be performed, even if performing them would lead to good consequences. This is the central thesis of deontology.

Kantian Ethics

The most famous deontologist is Immanuel Kant. Kantian ethics is firmly based in reason ; we can derive moral laws from rational precepts, according to Kant, and anyone who behaves immorally also behaves irrationally . He stated the moral law thus derived in the form of the Categorical Imperative, whic h in many ways resembles the biblical injunction to “do unto others as you would that they should do unto you.”

Imperatives are instructions; they tell us what to do. Kant distinguished between two types of imperative: hypothetical and categorical.

Hypothetical imperatives tell you what to do in order to achieve a particular goal : “If you want to have enough money to buy a new phone, then get a job”; “If you don’t want to go to prison, then don’t steal cars”.

Hypothetical imperatives only apply to people who want to achieve the goal to which they refer. If I don’t care about having enough money for a new phone, then “If you want to have enough money to buy a new phone, then get a job” doesn’t apply to me; it gives me no reason to get a job. If I don’t mind going to prison, then “If you don’t want to go to prison, then don’t steal cars” doesn’t apply to me; it gives me no reason not to steal cars.

Morality, according to Kant, isn’t like this. Morality doesn’t tell us what to do on the assumption that we want to achieve a particular goal, e.g. staying out of prison, or being well-liked. Moral behavio r isn’t about staying out of prison, or being well-liked. Morality consists of categorical imperatives.

Categorical imperatives, unlike hypothetical imperatives, tell us what to do irrespective of our desires . Morality doesn’t say “If you want to stay out of prison, then don’t steal cars”; it says “Don’t steal cars!” We ought not to steal cars whether we want to stay out of prison or not.

Morality, according to Kant, consists of categorical, rather than hypothetical, imperatives . The moral law does not prescribe moral action in order to achieve some end (e.g. the respect of one’s peers, or social collaboration); rather, it prescribes moral action irrespective of the ends that it achieves. This implies that we ought to obey the moral law no matter what our desires or inclinations.

Suppose that I, a rich Westerner, ought to make a contribution to charity to relieve poverty in the developing world, and that I am well aware of this fact. Suppose further that I would like to do so, that I care about the welfare of others and so that making such a donation will make me happy. When I make the donation, it is difficult to tell whether I am doing so out of duty (because I recognize that I ought to) or out of inclination (because I want to).

Kant holds that moral action must result from respect for the moral law. If I give money to charity because I want to, but I lack respect for the moral law and so if I didn’t want to make a donation then I wouldn’t, then in making the donation I am not acting well. My donation is at best benign, and at worst selfish; it is certainly not laudable.

If, on the other, I don’t want to give money to charity, but, because of my strong sense of duty, do so anyway, then this Kant would applaud. I may be mean, selfish, and heartless, but I respect the moral law. In conquering my inclination, I have acted well.

Because it is only when we act out of duty and contrary to inclination that our respect for the moral law is clear , such action has a special value for Kant. Indeed, Kant arguably valued such action more highly than action in accordance with both duty and inclination.

Divine Command Theory

A second deontological theory is divine command theory. Divine command theory holds that God’s commands are the source of ethics, that God is a moral authority and we ought always to obey his commands, irrespective of the consequences of doing so . Divine c ommand theory holds that morality is all about doing God’s will. God, divine command theorists hold, has issued certain commands to his creatures. We can find these commands in the Bible, or by asking religious authorities, or perhaps even just by consulti ng our moral intuition. We ought to obey these commands; that’s all there is to ethics.

There are several reasons for theists to be divine command theorists. If God is the creator literally all things, then he created morality.

If God rules over all Creation, then we ought to do what he tells us to do. The consistent message of the Bible is that we should obey

God’s commands.

The most famous argument against divine command theory is Euthyphro dilemma , which gets its name from Plato’s Euthyphro dialogue, which inspired it. The Euthyphro dilemma poses the question: Does God command the good because it is good, or is it good because it is commanded by God? However the divine command theorist answers this question, unacceptable consequences seem to arise.

Suppose that the divine command theorist takes the first horn of the dilemma, asserting that God commands the good because it is good. If God commands the good because it is good, then he bases his decision what to command on what is already morally good.

Mor al goodness, then, must exist before God issues any commands, otherwise he wouldn’t command anything. If moral goodness exists before God issues any commands, though, then moral goodness is independent of God’s commands; God’s commands aren’t the source of morality, but merely a source of information about morality. Morality itself is not based in divine commands.

Suppose, then, that the divine commands theorist takes the second horn of the dilemma, asserting that the good is good because it is commanded by God. On this view, nothing is good until God commands it. This, though, raises a problem too: if nothing is good until

God commands it, then what God commands is completely morally arbitrary; God has no moral reason for commanding as he does; morally speaking, he could just as well have commanded anything else. This problem is exacerbated when we consider that God, being omnipotent, could have commanded anything at all. He could, for example, have commanded polygamy, slavery, and the killing of the over-5 0s. If divine command theory is true, then had he done so then these things would be morally good. That doesn’t seem right, though; even if God had commanded these things they would still be morally bad. Divine command theory, then, must be false.

Agapism

A further deontological ethical theory, also influenced by the Christian tradition, is agapism. Agapism, which derives its name from the

Greek word “agape” meaning “love”, takes very seriously the great commandment of Mark 12:30-31: “you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart... you shall love your neighbour as yourself.” All of ethics, according to agapism, is summarised in this commandment. Agapism is a deontological system of ethics consisting of one simple command: in every situation, do the loving thing, whatever that may be.

Natural Law (classified as deontological because it leads to natural statements of duty, although arguably teleological because it is based on “telos,” purpose)

Natural Law says that everything has a purpose, and that mankind was made by God with a specific design or objective in mind

(although it doesn’t require belief in God). It says that this purpose can be known through reason. As a result, fulfilling the purpose of our design is the only ‘good’ for humans.

The theory of Natural Law was put forward by Aristotle but championed by Aquinas (1225-74). It is a deductive theory – it starts with basic principles, and from these the right course of action in a particular situation can be deduced. It is deontological, looking at the intent behind an action and the nature of the act itself, not its outcomes.

What is natural is, in general, to be followed because it is ethical and good to achieve natural goals and purposes. E.g., there is a natural tendency of things to continue their existence. Therefore, abortion is not allowed; embryonic or fetal research is not allowed if it results in destruction of the existence of the thing.

Causistry and Double Effect

Causistry is the name given to the process of applying Natural Law principles to specific situations. This is done in a logical way, as some principles have logical consequences. For example, if it is in principle wrong to kill innocent human beings, it follows that bombing civilian targets (such as Dresden in WW2) is wrong. However, if it is accepted that killing in self defence is okay, we could justify an air attack on Afghanistan on these grounds. Innocent people might die, but that is not the aim of the action, so the doctrine of double effect comes in to play.

Double effect refers to situations where there is an intended outcome and another significant but unintentional outcome. According to

Natural Law, it is our intentions that are important, not the consequences of our actions. Double effect would not allow you to perform an action where an unintended outcome had devestating effects. The unintended effect has to be PROPORTIONATE. What this actually means, critics say, is that Natural Law becomes like Utilitarianism.

Principle of double effect: if a violation of natural purpose can be predicted, but is not the intended goal of the violation, then it is not unethical as long as it is proportional in response . E.g., surgery to save a mother’s life which has a high probability of a fetus losing his/her life.

The purpose of humans - the Primary Precepts

In four words, 'Do good, avoid evil'. In more detail, Aquinas talked of Primary Precepts.

Remember: WORLD (acronym for Primary Precepts)

W orship God

O rdered society

R eproduction

L earning

D efend the innocent

S econdary Precepts

These are the rules - absolute deonotological principles - that are derived from the Primary Precepts. For example, the teleological principle "Protect and preserve the innocent" leads to rules such as "Do not abort," "Do not commit euthanasia" etc. These rules cannot be broken, regardless of the consequences. They are absolute laws.

‘Efficient’ and ‘Final’ Causes

This is Aristotle’s distinction between what gets things done (efficient cause) and the end product (final cause). With humans, it is the accomplishment of the end product that equates to ‘good’. An example is sexuality – an efficient cause of sex is enjoyment: because humans enjoy sex, the species has survived through procreation. However, the final cause of sex (the thing God designed it for) is procreation. Therefore sex is only good if procreation is possible.

Put another way, the efficient cause is a statement of fact or a description. If we ask why people have sex, we might talk about attraction, psychological needs etc. The final cause is a matter of intent – what was God’s purpose behind sex? The final cause assumes a rational mind behind creation, and as such moves from descriptive ethics (saying what is there) to normative ethics

(statements about what should or should not be the case).

Another example – did the soldier shoot well? The efficient cause deals with the set of events around the shooting – did he aim well, was the shot effective, di d the target die? These are descriptive points, and clearly don’t tell us about the morality of the shooting.

When we look into this area – was it right to kill? - we are evaluating his intent, and are asking about the final cause. We can then look at whether that cause is consistent with God’s design for human beings. We may decide that killing innocent people goes against God’s design for us, so it is always wrong to kill innocent people.

Real and Apparent Goods

Aquinas argued that the self should be maintained. As a result, Natural Law supports certain virtues (prudence, justice, fortitude and temperance) that allow the self to fulfil its purpose. Similarly there are many vices (the seven deadly sins) that must be avoided as they prevent the individual from being what God intended them to be.

Following a ‘real’ good will result in the preservation or improvement of self, getting nearer to the ‘ideal human nature’ that God had planned. There are many apparent goods that may be pleasurable (e.g. drugs) but ultimately lead us to fall short of our potential.

Reason is used to determine the ‘real’ goods.

God

Aquinas believed in life after death, which leads to a different understanding of God’s plan for humans. Natural Law can be upheld by atheists, but there seems no good reason for keeping to Natural Law without God. Aquinas holds that the one goal of human life should be ‘the vision of God which is promised in the next life’. This is why humans were made, and should be at the centre of Natural

Law thinking.

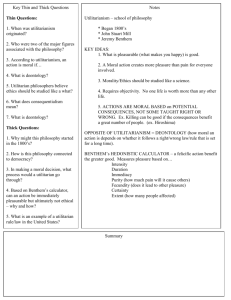

2. Outcome systems (consequentalist) – a division of teleological (purpose/goal) systems

Motivation = What will happen if I do “x”? a. Utilitarianism

Benthem and Mill, greatest good for greater amount of people, least harm

Act : Consider the outcomes of each act before action

Rule : Modern, act in a particular set of circumstances and context can be reasonably expected to create a set of outcomes, so we can have a rule to apply

Consequentialism is the theory that the moral status of an act is determined by its consequences. Consequentialism thus rejects both the virtue ethicist’s view that the moral status of an act is determined by the moral character of the agent performing it, and the deontologist’s view that the moral status of an act is determined by the type of act that it is. According to consequentialism, each of these factors is morally irrelevant. All that matters is what consequences an act leads to.

The only consequentialist theory of any plausibility is utilitarianism . Utilitarianism comes in many forms, but in each of them it holds that we ought to act in the way that has the best consequences, usually that we ought to maximize the good and minimize the bad.

Jeremy Bentham, an early utilitarian, proposed the hedonic calculus for working out the utility of an act. This method suggests that in order to discern whether an act is good we must consider the intensity, certainty, duration, propinquity, fecundity, purity, and extent of the pleasure and pain that it will cause.

“By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever, according to the tendency which it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question: or, what is the same thing in other words, to promote or to oppose happiness.”

Bentham’s theory of ethics is thus hedonistic; it holds that the only intrinsic good is pleasure, and that the only intrinsic bad is pain.

Everything else is good only insofar as it creates pleasure, and bad only insofar as it creates pain. Apart from pleasure and pain, nothing has any value at all.

The theory is utilitarian because it holds that the only thing that is relevant to the goodness or badness of an action is its effect on the amount of pleasure and pain in the world. Actions that bring more pleasure than pain into the world are good. Actions that bring more pain than pleasure into the world are bad. Whatever action maximizes the balance of pleasure minus pain is the right thing to do.

The most significant disagreement between the different forms of utilitarianism is in what they think that the good and the bad are: for example , hedonistic utilitarianism holds that the good is pleasure and that the bad is pain; ideal utilitarianism holds that there are other intrinsic goods than pleasure: beauty and knowledge, for example; preference utilitarianism holds that the good is preference satisfaction (i.e. people getting what they want) and that the bad is people not getting what they want.

There is also a question as to how we ought to set about maximizing utility. Act utilitarianism holds that we should consider the expected outcomes of each individual act before we decide whether or not to perform it. Rule utilitarianism disagrees, suggesting instead that we should follow those general rules maximize utility without worrying whether in this instance following the rule brings

about more pleasure than pain. Negative utilitarianism holds that maximizing pleasure is not important, that we should concern ourselves exclusively with minimizing suffering.

RM Hare’s two-level utilitarianism is an attempt to accommodate deontological intuitions within the framework of utilitarianism.

We all feel instictively that there are some acts that are just wrong, even if they do maximise utility, that there are some means that no end could ever justify. This is difficult to account for on utilitarianism, which holds that morality is all about achieving good ends, and so that no act is intrinsically right or wrong.

Hare’s two-level utilitarianism attempts to account for this feeling from a utilitarian perspective. Two-level utilitarianism holds that act utilitarianism is true, but that we ought to operate practically as if rule utilitarianism were true, because that is the approach that maximises utility.

In an ideal situation, Hare holds, we ought to act as act utilitarians. Given sufficient time to calculate the consequences of each of the various courses of action open to us, and sufficient foresight to do so accurately, we ought to perform whatever act it is that maximises utility. We do not, however, have either that much time or that much foresight. Utilitarianism must therefore be adapted to the circumstances of the real world.

The approach to ethical decisions that will serve us best in practice is not act utilitarianism, but rule utilitarianism. Attempting to perform utilitarian calculations that we just don’t have time to do won’t maximize utility. What will maximize utility is having a set of rules that generally tell us what to do without too much fuss. We therefore ought, because of our limitations, to act in accordance with rules.

Further, it’s good for us to have a strong attachment to these rules. The rules are generally reliable, and it is therefore good for us to be very reluctant to break them. This is where our deontological intuitions come in: they help us to maximize utility.

In this way, then, Hare combines act utilitarianism with rule utilitarianism, and explains our attachment to the idea that certain acts are intrinsically wrong.

Ideal utilitarianism, like most forms of utilitarianism, is concerned solely with maximizing the good. We always ought to act, according to the ideal utilitarian, in whatever way brings about the best consequences.

What is distinctive about ideal utilitarianism is its view as to what the good is, as to what it is that we ought to try to bring about. The ideal utilitarian, unlike the hedonistic utilitarian, is not concerned only with happiness, but also with other intrinsic goods, such as beauty or knowledge. A leading advocate of ideal utilitarianism was GE Moore.

Hedonistic utilitarianism holds that the only intrinsic good is pleasure, that everything else is valuable only insofar as it causes pleasure. Hedonistic utilitarianism therefore holds that we ought to act in whatever way maximizes pleasure.

The ideal utilitarian, however, disagrees w ith the hedonistic utilitarian’s narrow definition of the good. According to the ideal utilitarian, there is more to life than pleasure. A great work of art, for instance, is valuable not only because it causes pleasure in those who appreciate it, but also in itself.

To see the difference, imagine a great work of art in a world of Phillistines. The work of art, though a good one, is unappreciated due to the ignorance of the general population. One of the Phillistines suggests that it would be fun to burn the work of art; the others agree.

Is what they propose to do a good thing or a bad thing?

According to the hedonistic utilitarian, the Phillistine’s suggestion is a good one. However good the work of art may be, it isn’t bringing pleasure to anyone. Burning it will be fun; the Phillistines should therefore burn it.

According to the ideal utilitarian, the Phillistine’s suggestion is probably a bad one. Though the work of art goes unappreciated, it is nevertheless intrinsically valuable. This lasting intrinsic value must be weighed against the fleeting value of the pleasure that the

Phillistines will get from burning it. In all probability, the aesthetic value of the work of art will be deemed more important; it should not be burned.

The ideal utilitarian thus thinks that hedonistic utilitarianism, though along the right lines, is too simplistic. When deciding what to do, we should not think solely in terms of pleasure and pain, but should also take into account other goods.

It certainly seems that there is more to life than just pleasure and pain. Robert Nozick developed a thought-experiment to demonstrate this:

“Suppose there were an experience machine that would give you any experience you desired. Superduper neuropsychologists could stimulate your brain so that you would think and feel you were writing a great novel, or making a friend, or reading an interesting book.

All the time you would be floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain. Should you plug into this machine for life, preprog ramming your life’s desires?”

Nozick’s machine guarantee’s happiness, which is all that the hedonistic utilitarian wants. There is a price to be paid for this happiness, though: those on the machine never actually do anything more than float in a tank having their brain stimulated. The question we must ask ourselves in order to decide whether we would want to be plugged into such a machine is this: is happiness all that matters, or is it important that we actually do something with our lives?

Plausibly, we should not plug ourselves into Nozick’s experience machine. Most people agree that they would not want the kind of life that it offers. If that is the case, though, then happiness isn’t everything; how our lives actually go matters as well as whether or not we enjoy them. This supports the objective utilitarian’s claim that what is good is an objective, rather than merely a subjective, matter.

Objective utilitarianism holds that it is this objective goodness that is to be maximized.

Preference utilitarianism holds that the good is preference satisfaction, i.e. getting what we want, and that the bad is the opposite, i.e. not getting what we want. The best known preference utilitarian is Peter Singer .

People may be mistaken about what will make them happy. It may be I think that going to the pub and downing six pints of lager will make me happy, but that I would actually be happier staying at home and reading Dostoyevksy.

Negative utilitarians are concerned only with minimizing the bad . The y don’t that we ought to maximize the good and minimize the bad, and that when we must choose between the two we must weigh the difference that we can make to the one against the

difference that we can make to the other; rather, negative utilitarians hold just that we ought to minimize the bad, that we ought to alleviate suffering as far as we are able to do so.

Suppose that I have a choice to make: I can either make the happiest man in the world even happier than he already is, or I can alleviate some of the suffering of the unhappiest man in the world. Suppose further that the difference that I can make to the happy man is much greater than the difference that I can make to the unhappy man.

Most utilitarians would say that in this case I ought to help the happy man. As I can make a greater difference to the life of the happy man than I can make to the life of the unhappy man, it is the happy man whom I should help.

Negative utilitarians disagree. Negative utilitarians hold that it is more important to alleviate suffering than it is to promote pleasure, and that I should therefore always choose to alleviate suffering rather than promote pleasure when forced to choose between the two.

The big problem with negative utilitarianism is that it appears to require the destruction of the world. The world contains much suffering, and the future, presumably, contains a great deal more suffering than the present. Each of us will suffer many calamities in the course of our lives, before those lives finally end with the suffering of death.

There is a way, however, to reduce this suffering: we could end it all now. With nuclear weapons technology, we have the capability to blow up the planet, making it uninhabitable. Doing so would cause us all to suffer death, but death is going to come to us all anyway, so causing everyone to die will not increase the suffering in the world. Causing us to die now, though, will decrease the suffering in the world; it will prevent us from suffering those calamities that were going to plague us during the remainder of our lives.

Destroying the planet, then, will reduce the suffering in the world. According to negative utilitarianism, then, it is what we ought to do.

That, though, is surely absurd. Negative utilitarianism, therefore, is false.

In such a case, the hedonistic utilitarian would say that it is better if I stay at home and read Dostoyevsky; that, after all, is what will make me happiest. The preference utilitarian, though, would say that it is better if I go to the pub; that is what I want to do, and what matters is that I get what I want.

There are a number of strengths to utilitarianism: it proposes a practical method for working out what to do, it upholds equality, and it accords without intuition that ethics is primarily about making the world better. It also, however, faces some strong objections.

There are a number of objections to it:

Utilitarianism is Impractical

One problem with utilitarianism is that it is impractical to stop to calculate the utility of the expected outcomes of our various options every time that we have to make a decision. The utilitarian has an answer to this, though: if making careful calculations for every decision doesn’t maximize utility, then we ought not do so; as we’re better, in most cases, to make a rough estimate (which we generally do) and then just get on with it, that’s what utilitarianism says that we should do.

We Can’t Predict the Consequences of an Action

A stronger version of this objection is that we cannot know what the consequences of any action will be, and so cannot assess its moral value. We may be able to make a guess at the short-term consequences, but this will only be a guess, and the long-term consequences will be impossible to predict. If a butterfly flapping its wings can effect a hurricane, then how can we predict the outcome of any course of action?

Utilitarianism is too Demanding

Utilitarianism holds that we ought always to do whatever it is that maximizes utility. That places a great burden upon us. Every time I read a newspaper, or watch TV, there’s something else that I could do (e.g. help out at the homeless shelter, write a letter to my grandmother) that will bring more utility into the world. If utilitarianism is right, then reading a newspaper is therefore morally wrong.

According to utilitarianism, those of us who aren’t facing great hardship ought always to be helping those that are, because that’s what maximiz es utility. That, though, is implausibly demanding; reading a newspaper isn’t a sin.

Utilitarianism Ignores Distributive Justice

A huge problem with utilitarianism is that it ignores distributive justice. Utilitarianism seeks to bring as much happiness into the world as possible, but it doesn’t care who gets it. Some people, though, deserve happiness more than others. We should give preference to people who deserve to be happy, or at least who haven’t brought their suffering upon themselves. Utilitarianism cannot account for this.

Sometimes the End Doesn’t Justify the Means

Because utilitarianism focuses exclusively on the consequences of actions, it entails that no act is intrinsically good or bad; according to utilitarianism, acts are good only insofar as the increase utility and decrease pain, and bad only insofar as they do the opposite. This means that no act is intrinsically better than any other. Some acts, though, do seem to have intrinsic value; some acts seem to be wrong irrespective of their consequences. It is simply wrong to kill innocent children, even if doing so creates more pleasure than it does pain. This is inconsistent with utilitarianism.

3. Virtue ethics

Motivation = What would a virtuous person do? a. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, golden mean=not excessive, not deficient b. Hursthouse, Anscombe, modern virtue ethicists, who use virtue ethics to try to reconcile the problems between duty systems and outcome systems.

Virtue ethics goes back to the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. According to virtue theory, ethics is primarily about agents, not actions. Being good is thus seen as primarily a matter of character rather than of deeds.

The first task for the virtue theorist is that of providing an account of the virtues. In general terms, virtues are character traits, dispositions to act in certain ways, that it is good to possess. They are to be contrasted with vices, character traits that it is bad to possess.

On Aristotle’s account, virtues always fall between two extremes, vices of excess and deficiency . The virtue courage thus falls between foolhardiness (a vice of excess) and cowardice (a vice of deficiency).

There are several traditional lists of virtues, such as that of the cardinal virtues, telling us how it is good for us to be. According to

Aristotle, the way to acquire these virtues is through habituation, practice.

Virtue theory has a number of strengths that give it an advantage over other approaches to ethics. In particular, it does not rely on any concept of a divine law, and does not reduce ethics to action.

Strengths of Virtue Ethics

Virtue ethics sets aside questions as to what we ought to do and instead concentrates on the question as to what type of people we ought to be. Moral goodness, it suggests, is primarily a matter of character, rather than of action.

After a period of neglect, virtue ethics has recovered popularity in recent decades. Anscombe and Alasdair MacIntyre have been particularly influential in this process. There are several appealing features of virtue ethics that account for this return to prominence.

One important factor in the revival of virtue ethics has been a growing dissatisfaction with rule-based systems of ethics. Elizabeth

Anscombe argued that the concept of moral duty rests on theological background assumptions. The idea of moral duty presupposes the existence of a moral law. Classical theism holds that God instituted such a law, and so that we do have obligations of this kind.

With the decline of classical theism, though, there is no longer widespread belief in the theological assumptions that ground the concept of moral obligation. We should therefore, Anscombe suggested, jettison the concept of obligation from morality. Talk of moral duty no longer makes any sense.

This proposal, if it were accepted, would undermine those ethical traditions that rest on concepts of obligation. Virtue ethics, though, would survive the revolution untouched. The first strength of virtue theory is therefore that it has no need of outdated concepts of moral obligation.

The main strength of virtue theory, though, is that unlike other ethical traditions it affords a central role to character. Other ethical theories neglect this aspect of morality. Kantian ethics, for example, holds that it is important to act out of duty rather than inclination, that whether or not you want to do the right thing is irrelevant; all that matter is whether or not you do it.

Character, though, does seem to be important. One who helps the poor out of compassion does seem to be morally superior to one who helps the poor out of a grudging respect for duty. Virtue theory can account for this; other theories, arguably, cannot.

It is also, however, subject to several objections. For all its advantages, there are some drawbacks to virtue theory. These are some of the problems that its advocates face:

The Relativity of Virtue

An initial difficulty for virtue theory is that of identifying the virtues. If there is an objective list of virtues, then it is difficult to overcome cultural prejudice in saying what goes on it. Indeed, it might plausibly be thought that virtues are culturally relative. At the risk of stereotyping, compare the British taste for self-deprecation and humility with the American style of confidence and self-belief; which is the more virtuous approach?

Application

There is also the question of how to apply virtue theory to moral dilemmas. Virtue theory tells us to exhibit virtues, to act as the virtuous person would act, but if we don’t already know that it is difficult to work out. What, for instance, is the virtuous stance to take on the issue of stem-cell research, or abortion?

When Virtues are Vices

Virtue theory appears to commend some behavior that we would generally view as immoral. For instance, soldiers fighting unjust wars for oppressive regimes seem to exhibit courage. That does not, however, make them morally good.

Supererogation

There is also a difficulty in accounting for supererogation, acting with exceptional goodness. Consider a rich Westerner who sells their possessions and relocates to a country in the developing world, giving the money that they save to the poor. We would normally think that someone who does this is to be applauded, even if we do not feel duty bound to follow their example ourselves.

On virtue theory, however, such acts as these are judged to be indicative of vice. For each virtue, remember, there are corresponding vices of excess and deficiency. The virtue of generosity, then, will fall between the vices of meanness and extravagence. To be as generous as the rich Westerner, surely, is to be extravagant. Virtue theory, then, would say that the rich Westerner’s actions betray a flaw in their character, a vice.

Meta-Ethics: asks about the nature of goodness and badness, what is to be defined as morally right or wrong; abstract

1. Moral Realism and Antirealism

Perhaps the biggest controversy in meta-ethics is that which divides moral realists and antirealists.

Moral realists hold that moral facts are objective facts that are out there in the world . Things are good or bad independent of us, and then we come along and discover morality.

Antirealists hold that moral facts are not out there in the world until we put them there, that the facts about morality are determined by facts about us.

On this view, morality is not something that we discover so much as something that we invent.

2. Cognitivism and Noncognitivism

Closely related to the disagreement between of moral realists and antirealists is the disagreement between cognitivism and noncognitivism.

Cognitivism and noncognitivism are theories of the meaning of moral statements.

According to cognitivism, moral statements describe the world . If I say that lying is wrong, then according to the cognitivist I have said something about the world, I have attributed a property wrongness to an act lying. Whether lying has that property is an objective matter, and so my statement is objectively either true or false.

Cognitivists hold that moral statements are descriptive , they attribute real moral properties to people or actions. There are two types of cognitivist: naturalists and non-naturalists.

a. Naturalists hold that moral properties are natural properties. This means that it is possible to give a complete analysis of morality in non-moral terms, to reduce the moral to the non-moral. b. Non-naturalists hold that moral properties are not natural properties, but rather are a unique kind of property that cannot be explained in any other terms. Just as Cartesian dualists hold that there are two fundamentally different kinds of entity in the world, physical and mental, and that neither can be explained in terms of the other, so the ethical non-naturalist holds that there are two fundamentally different kinds of property in the world, non-moral and moral, and that morality cannot be reduced to non-moral terms.

Ethical non-naturalists tend to be intuitionists. Non-naturalists hold that moral properties are fundamentally different to non-moral properties, and so cannot be analyzed in non-moral terms. To attempt a reductive analysis of morality is, according to non-naturalists, futile; there can be no such analysis.

This raises a problem for moral epistemology: if moral properties are fundamentally different to non-moral properties, then how can we learn moral facts? It is only the physical world that can be experienced through the five senses, so if morality is not a part of the physical world then it is mysterious how we can come to possess moral knowledge.

Intuitionism is a response to this problem; it postulates the existence of a special moral intuition, a sixth sense, by which we can perceive the moral realm. According to intuitionists, we acquire knowledge of morality by intuition; moral facts are evident to us.

Noncognitivists disagree with this analysis of moral statements. According to noncognitivists, when someone makes a moral statement they are not describing the world; rather, they are expressing their feelings or telling people what to do. Because noncognitivism holds that moral statements are not descriptive, it entails that moral statements are neither true nor false. To be true is to describe something as being the wa y that it is, and to be false is to describe something as being other than the way that it is; statements that aren’t descriptive can’t be either.

Emotivism is the noncognitivist metaethical theory according to which all moral statements are mere expressions of our attitudes.

An emotivist would analyse a moral statement such as “It’s morally good to give money to charity” as equivalent to “Hurray for giving money to charity!” Similarly, according to emotivism the statement “It’s wrong to take innocent lives” means merely “Boo to taking innocent lives!”.

For this reason, emotivism is sometimes referred to as “Boo-Hurray theory”.

Emotivism is a noncognitivist theory because it holds that moral statements are neither true nor false, and so cannot be known.

“Hurray for giving money to charity!” is no more true or false than “Hurray for marshmallows”; it is just an expression of one’s feelings.

Other Systems and Theories

1. Egoism is a teleological theory of ethics that sets as its goal the benefit, pleasure, or greatest good of the oneself alone . It is contrasted with altruism, which is not strictly self-interested, but includes in its goal the interests of others as well. There are at least three different ways in which the theory of egoism can be presented:

Psychological Egoism -- This is the claim that humans by nature are motivated only by self-interest (Ayn Rand). Any act, no matter how altruistic it might seem, is actually motivated by some selfish desire of the agent (e.g., desire for reward, avoidance of guilt, personal happiness). This is a descriptive claim about human nature. Since the claim is universal--all acts are motivated by self interest--it could be proven false by a single counterexample.

It will be difficult to find an action that the psychological egoist will acknowledge as purely altruistic, however. There is almost always some benefit to ourselves in any action we choose. For example, if I helped my friend out of trouble, I may feel happy afterwards. But is that happiness the motive for my action or just a result of it? Perhaps the psychological egoist fails to distinguish the beneficial consequences of an action from the self-interested motivation. After all, why would it make me happy to see my friend out of trouble if I didn't already have some prior concern for my friend's best interest? Wouldn't that be altruism?

Ethical Egoism -- This is the claim that individuals should always to act in their own best interest. It is a normative claim. If ethical egoism is true, that appears to imply that psychological egoism is false: there would be no point to saying that we ought to do what we must do by nature.

But if altruism is possible, why should it be avoided? Some writers suggest we all should focus our resources on satisfying our own interests, rather than those of others. Society will then be more efficient and this will better serve the interests of all. By referring to the interests of all, however, this approach reveals itself to be a version of utilitarianism, and not genuine egoism. It is merely a theory about how best to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number.

An alternative formulation of ethical egoism states that I ought to act in my own self-interest--even if this conflicts with the values and interests of others--simply because that is what I value most. It is not clear how an altruist could argue with such an individualistic ethical egoist, but it is also not clear that such an egoist should choose to argue with the altruist. Since the individualistic egoist believes that whatever serves his own interests is (morally) right, he will want everyone else to be altruistic. Otherwise they would not serve the egoist's interests! It seems that anyone who truly believed in individualistic ethical egoism could not promote the theory without inconsistency. Indeed, the self-interest of the egoist is best served by publicly claiming to be an altruist and thereby keeping everyone's good favor.

Minimalist Egoism -- When working with certain economic or sociological models, we may frequently assume that people will act in such a way as to promote their own interests. This is not a normative claim and usually not even a descriptive claim. Instead it is a minimalist assumption used for certain calculations. If we assume only self-interest on the part of all agents, we can determine certain extreme-case (e.g., max/min) outcomes for the model. Implicit in this assumption, although not always stated, is the idea that altruistic behavior on the part of the agents, although not presupposed, would yield outcomes at least as good and probably better.

2. Pluralism —deontological, but recognizes there are sets of many duties, with a limited set of universal rules that may have exceptionalities (tolerated though not ethical behavior)

W. D. Ross, argues that our duties are “part of the fundamental nature of the universe.”

Set of duties, according to Ross:

* non-malificence: do not harm

* beneficence: do good, benefit

* justice: treat equals equally

* add autonomy: respect individuals

* fidelity: be faithful

* reparation: return good for good

* gratitude

* self-improvement

There are several prima facie duties that we can use to determine what, concretely, we ought to do. A prima facie duty is a duty that is binding (obligatory) other things equal, that is, unless it is overridden or trumped by another duty or duties . Another way of putting it is that where there is a prima facie duty to do something, there is at least a fairly strong presumption in favor of doing it. An example of a prima facie duty is the duty to keep promises. "Unless stronger moral considerations override, one ought to keep a promise made."

Ross recognizes that situations will arise when we must choose between two conflicting duties. In a classic example, suppose I borrow my neighbor’s gun and promise to return it when he asks for it. One day, in a fit of rage, my neighbor pounds on my door and asks for the gun so that he can take vengeance on someone. On the one hand, the duty of fidelity obligates me to return the gun; on the other hand, the duty of nonmaleficence obligates me to avoid injuring others and thus not return the gun. According to Ross, I will intuitively know which of these duties is my actual duty, and which is my apparent or prima facie duty. In this case, my duty of nonmaleficence emerges as my actual duty and I should not return the gun.

3. Relativism

—determining the ethics of action is dependent either on the individual or on the group/community (metaethical)

The second and more this-worldly approach to the metaphysical status of morality follows in the skeptical philosophical tradition, such as that articulated by Greek philosopher Sextus Empiricus, and denies the objective status of moral values. Technically, skeptics did not reject moral values themselves, but only denied that values exist as spirit-like objects, or as divine commands in the mind of God.

Moral values, they argued, are strictly human inventions, a position that has since been called moral relativism. There are two distinct forms of moral relativism. The first is individual relativism, which holds that individual people create their own moral standards.

Friedrich Nietzsche, for example, argued that the superhuman creates his or her morality distinct from and in reaction to the slave-like value system of the masses. The second is cultural relativism which maintains that morality is grounded in the approval of one ’s society

– and not simply in the preferences of individual people. This view was advocated by Sextus, and in more recent centuries by

Michel Montaigne and William Graham Sumner. In addition to espousing skepticism and relativism, this-worldly approaches to the metaphysical status of morality deny the absolute and universal nature of morality and hold instead that moral values in fact change from society to society throughout time and throughout the world. They frequently attempt to defend their position by citing examples of values that differ dramatically from one culture to another, such as attitudes about polygamy, homosexuality and human sacrifice.