Cole Walker LA Coastline Maco 455 Word Count: 1050 https

advertisement

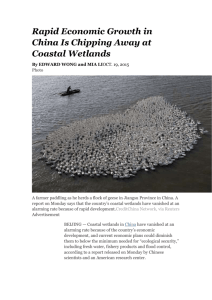

Cole Walker LA Coastline Maco 455 Word Count: 1050 https://dwalker14blog.wordpress.com/2015/10/08/louisiana-coastline-story/ The coastal region of Louisiana has suffered from severe land loss over the past several years. Land in the coastal region of Louisiana has disappeared over the past 10 to 15 years. According to Restore or Retreat, a non-profit coastal advocacy group dedicated to improving the Louisiana coastline, Louisiana is losing 25 to 35 square miles of wetlands per year and the highest rates are occurring in the Barataria and Terrebonne basins at 10 and 11 square miles per year. If the rate of land loss remains consistent, by 2050, an area of 640,000 acres, about the size of Rhode Island, will be underwater, it reported. The Times Picayune reported that the United States Geological Survey said that the yearly amount of land loss is equal to about a football field worth of land per hour. The land loss crisis began with The Great Flood of 1927, according to the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority. The Great Flood of 1927 was reported as one of the worst natural disasters in the history of the United States. In 1928, Congress passed the Flood Control Act, which authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to design and construct a flood protection system to control the floods caused by the Mississippi River each year. Each spring the Mississippi River would overflow, causing massive flooding around its tributaries, Environmental Scientist and Invasive Species Coordinator for Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program, Michael Massimi, said. “After the flood in 1927, people knew that we needed to build some sort of levee system to control flooding. When we did that, the river couldn’t overflow like it used to. This was the start of coastal erosion for us,” Massimi said. Once the levee system was formed, the river was forced to flow in a certain direction, many of its tributaries were blocked and it had no choice but to go in the path formed by the levees, he said. Each year when the river would flood, it deposited sediment and nutrients into the wetlands, giving them food they need to eat and in a sense, giving them life, Massimi said. The levees stopped the river from doing this. In the 1950s to 1960s, canals were being dug for pipelines and flowlines, Massimi said. “The problem with digging all of these canals was that the land in this region was already sinking, so we cut it up and made it look like Swiss cheese. Now it is not only sinking, but smaller pieces are just disappearing,” he added. A large piece of land sinks slower than a smaller piece, so cutting the land up into several small pieces caused problems, he said. Another problem with digging canals in the wetlands is that when the canals were dug it stopped the wetlands from receiving some nutrients because of spoil banks, Massimi said. Spoil banks are formed when people dig a canal and leave all of the dug up mud and dirt, “spoil,” on the banks of the new canal, he said. The spoil banks stopped the nutrients from getting from the canal to the surface of the wetlands. The canals were dug in a relatively straight line. A problem with the canals being dug in a straight line is salt-water intrusion, Massimi said. Salt-water intrusion is when salt water from the ocean is pushed inland and into the wetlands. With the canals being relatively straight, it is easier for the salt-water to travel farther up stream, he said. Most of the time, the quickest and easiest way from point A to point B is in a straight line. Sea level rise is also a reason for the coastline being diminished, Massimi said. “Our subsidence level is lower than our sea level rise. In Grand Isle, we subside seven millimeters per years and the sea level rises two millimeters per year,” he said. Scientific American reported that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said, “By 2100, the Gulf of Mexico could rise as much as 4.3 feet across the landscape, which has an average elevation of about three feet. If this happens, everything outside of the protection levees, most of Southeast Louisiana, would be underwater.” In 1990, Congress enacted the Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act (CWPPRA). The CPRA reported, “CWPPRA was the first federally mandated restoration effort to take place along Louisiana’s coast and the first program to provide a stable source of federal funds dedicated specifically to coastal restoration.” Massimi said that there has been close to 100 coastal restoration projects done by CWPPRA, including: shoreline protection, marsh creations, river diversions, hydraulic restoration (leveling spoil banks), oyster reef projects, bank stabilization, barrier island restoration, and ridge reconstruction. In 2005, the CPRA, Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, was put in charge of coastal restoration in Louisiana and currently still is. The CPRA plays the largest part in trying to save the wetlands, Massimi said, adding that they are in charge of making the “master plan.” The two most effective forms of restoration done by the CPRA are marsh creations and river diversions, Massimi said. A marsh creation is when sediment is pumped from one place to another using dredges. Marsh creations are fast and effective ways to restore the coastline, Massini said, but they are only a short-term fix to a long-term problem. River diversions are a more complicated solution and much more expensive. River diversions are intended to introduce freshwater out of rivers and into the wetlands, giving the wetlands nutrients and sediment, Massimi said. He added that river diversions help plants grow and build new land. The freshwater also combats salt-water intrusion. “The problem with river diversions is that they are extremely expensive and tend to be controversial. They can have a negative impact on certain species of fish and they can also increase flood risk,” he said. The CPRA is trying to find a safe and easier way of creating river diversions, he added. “This was kind of inevitable, you think back to when we built the levees. That was the start of it. We needed the levees, we couldn’t have made it without them, but they were not necessarily good for us in the long run,” Massimi said. “Coastal erosion is a natural process, we just learn to live with it and always will,” he added.