Legal Advice-1934 Act-30 May2011 - Local Government Association

advertisement

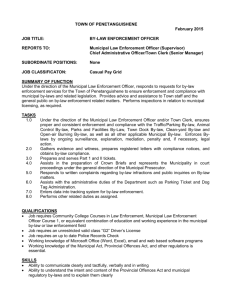

Our Ref: MJK:ksm:101705 Your Ref: 9 February 2016 Ms Andrea Malone Local Government Association of South Australia GPO Box 2693 ADELAIDE SA 5001 VIA EMAIL: andrea.malone@lga.sa.gov.au Dear Andrea LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 1934: REPEAL OF BY-LAW PROVISIONS I refer to your request for advice in relation to the repeal of the by-law making provisions under section 667 of the Local Government Act 1934 in their entirety and the expiry of regulation 13(1) of the Local Government (Implementation) Regulations 1999. Specifically, you seek advice as to whether the repeal and expiry of these provisions would leave any "gaps" in Councils' compliance regime and have a significant impact on the ability to enforce 'reasonable requirements'. In preparing this advice, I have had regard to the views expressed by the Office of State Local Government Relations (OSLGR) in relation to the alternative legislation that (in his view) achieves the same or similar purposes as these by-law making provisions. 1. 1 Uses and Licences – Lodging Houses & Taxi Services 1.1. A Council's ability to regulate lodging houses and taxi services through the provision of a license upon application is an express power under section 667(1).3 of the 1934 Act. The repeal of this section will remove powers of Councils to regulate these matters. 1.2. Before making any determination with respect to the repeal of these provisions, the policy question to be determined is whether it is appropriate for Councils to continue to regulate these matters or, whether it is sufficient for them to be subject to applicable existing State legislation. Relevant considerations in this regard include the extent to which the provisions are currently relied upon by Councils1 and for the Council's that do so, their effectiveness in regulating lodging houses and taxi services, the cost to Councils and the resources required to regulate these matters as against any revenue obtained by the Council in doing so. This information can be ascertained through consultation with Councils, which must be a necessary pre-condition to any proposed repeal process. Four Councils have adopted by-laws in relation to lodging houses. There are currently no taxi by-laws in operation, however, the City of Mount Gambier is in the process of adopting a new Taxi By-law in reliance upon its powers under section 667(1).3 of the 1934 Act as its previous Taxi By-law expired as of 1 January 2011. Document1 Ms A Malone -2- 9 February 2016 1.3. It does not appear necessary for Councils to regulate lodging houses for the reasons identified by OSLGR and because the matter can be adequately managed by (and left to) private action by individuals within the realms of the existing residential tenancy law. The Residential Tenancies (Rooming Houses) Regulations 1999, in conjunction with relevant common law principles, provide a degree of protection to both tenants in lodging houses and their landlords. The fact that so few Councils regulate lodging houses under by-law may be regarded as testament to this. 1.4. In relation to taxi services, I understand that only the City of Mount Gambier seeks to regulate the local country taxi service. Whilst the 2003 by-law has expired the City is currently preparing a successor by-law for consultation with the community. The Passenger Transport Act 1994 and Passenger Transport Regulations 2009 extend to country taxi services. This means that where a Council in a regional area chooses not to regulate taxi services under the provisions of a by-law, any taxi service that operates in that area is bound by the requirements of this legislation (which affords adequate protection to passengers). The Passenger Transport legislation does not, however, provide a means to limit taxi numbers within a prescribed area whereas this may be achieved under a by-law (being the reason that the by-law power has been identified as one which has the capacity to restrict competition). Regardless, the Passenger Transport legislation is intended to be sufficient to regulate taxi services. Therefore subject to consultation with regional Council's and, in particular the City of Mount Gambier, these provisions may be repealed. 2. Nuisances and Health 2.1. Section 667(1).4 of the 1934 Act empower Councils to make by-laws 'for the prevention and suppression of nuisances'. Councils have, in recent times, increasingly relied upon this power to make by-laws to address matters including waste management, nuisances caused by building sites and bird scaring devices. Waste Management 2 2.1.1 The purpose of existing waste management by-laws is to regulate the manner in which waste is stored on private premises and the manner in which it is left for collection by a Council. These by-laws are made solely in reliance upon the nuisance and 'good government' by-law making powers. 2.1.2 To the extent that such by-laws regulate the manner in which waste is to be left out (on the kerbside) for collection by the Council, I agree with OSLGR that a viable option to achieve this objective (other than a waste management by-law) is for a Council to establish guidelines with which any person wishing to use the waste collection services provided by the Council must comply (i.e. as provider of a waste collection service, the Council may require that waste be left for collection in a specified manner (i.e. in a prescribed receptacle))2. A Council may then decline to collect kerbside waste that does not comply with any such guidelines. To clarify, I disagree that it is the imposition of a service charge under section 155 of the Local Government Act 1999 for waste collection that gives rise to an automatic power on the part of Councils to impose conditions or guidelines in relation to the provision of that service. Document1 Ms A Malone -3- 9 February 2016 2.1.3 Where waste is deposited on the kerbside other than in accordance with any applicable Council guidelines for disposal, this may constitute an expiable offence under section 235 of the 1999. It is acknowledged, however, that a Council's ability to expiate an offence under section 235 is contingent upon the identity of the person who deposits rubbish being known by the Council (which may not always be the case). However, this evidentiary burden equally applies to enforcing breaches of a waste management by-law. 2.1.4 To the extent that waste management by-laws regulate the manner in which waste is stored on private premises, regulation 4 of the Public and Environmental Health (General) Regulations 2006 achieves the same purpose. This provision applies only in respect of the manner in which waste is stored on private premises and does not assist with respect to the regulation of waste placed on the kerbside for collection by a the Council. 2.1.5 Further, a Council's power to issue an order under section 254 of the Local Government Act 1999 to deal with the unsightly condition of land, is not enlivened in circumstances where refuse is allowed to accumulate on the kerbside. This order-making power applies only in respect of private land. In practical reality, the order making provisions under the 1999 Act are of limited effect in dealing with an accumulation of waste on private land. It is more appropriate for a Council to rely on its enforcement powers to address insanitary conditions on land under the Public and Environmental Health Act 19873 in these circumstances. 2.1.6 Taking the above into account, my view is that the options referred to above are all viable alternatives to a waste management by-law to regulate (and enforce) the manner in which waste is left by the kerbside for collection by a Council and the storage of waste on private premises. Nuisances Caused by Building Sites 3 2.1.7 By-laws that regulate this subject matter address the nuisance caused by rubbish escaping from land upon which building work is being undertaken. Such by-laws ordinarily require persons who are in charge of building work to ensure materials on the land are properly secured so they do not escape from the land, usually when there are windy conditions. 2.1.8 I concur that conditions designed to prevent pollution caused by building sites may be attached to a grant of development approval but I also recognise that this is not a realistic proposition. In practice, enforcing such condition (i.e. by first issuing a notice under section 84 of the Development Act 1993 and then expiating a failure to comply with the notice) is not an effective way to deal with the issue. Enforcement under the Development Act is a cumbersome and lengthy process. Councils can, for good reason, be reticent to pursue this course of action given appeal rights are often exercised by recipients of notices (which gives rise to action in the Environment, Resources and Development Court and a commitment of Council resources accordingly). See, for example, Council's powers under sections 15 and 16 of the Public and Environmental Health Act 1987. Document1 Ms A Malone -4- 9 February 2016 2.1.9 The environmental nuisance offence provisions under the Environment Protection Act 1993 may apply in relation to pollution originating from a building site. Conceivably, the definition of 'environmental nuisance' may, in certain circumstances, extend to rubbish and other waste materials that escape from a building site, thereby polluting surrounding areas. In which case, a person responsible for a building site who fails to take adequate action to prevent rubbish escaping from the site may be guilty of an offence (for causing an environmental nuisance) under section 82 of the EP Act. However, there are factors that limit a Council's ability to effectively enforce this matter under the EP Act. 2.1.10 First, a Council that does not have any officers appointed as authorised officers under the EP Act does not have the ability to regulate such offences. Rather, the Council would have to rely upon officers of SAPOL or the Environment Protection Agency to take enforcement action, which may not always result in a satisfactory (or any) outcome. 2.1.11 Secondly, in order to establish this offence under the EP Act, it is necessary to prove that the rubbish escaping from the building site is, in fact, an 'environmental nuisance' as defined. This can be an onerous task. It would, for example, be difficult to prove that an 'environmental nuisance' for the purposes of the EP Act includes paper and plastic blowing from a building site to a localised area (such as onto the footpath), which is the mischief that a building sites by-law is intended to curtail. Rather, the definition of 'environmental nuisance' under the EP Act captures nuisances that have a wideranging impact and affect the amenity of a greater area. 2.1.12 Conversely, the evidentiary burden to establish an offence under a building sites by-law is not as onerous. That is, a breach of the bylaw (and an offence) occurs where any amount of paper, plastic or other building materials blow from a building site in a wind. 2.1.13 For this reason, by-laws that address rubbish emanating from a building site (made in sole reliance upon the nuisance by-law making power) have provided an effective and immediate solution for Council's in relation to nuisance issues arising from litter originating from a building site. 2.1.14 For the Councils that have adopted such a by-law, it would be worthwhile ascertaining how often the by-law is relied upon and/or enforced. This information will assist in forming a view as to whether the retention of the nuisance power to enable by-laws for this purpose is required. Bird Scaring Devices Document1 2.1.15 I agree that the Environment Protection (Noise) Policy 2007 and the Audible Bird Scaring Devices Environmental Noise Guidelines 2007 are relevant considerations in relation to nuisances caused by bird scaring devices. 2.1.16 It must be noted, however, that as outlined above, the enforcement options under the EP Act are, as a matter of practical reality, of limited effect in addressing such nuisances in comparison to a bylaw. Ms A Malone 3. -5- 9 February 2016 2.1.17 A breach of the Noise Policy does not automatically give rise to an offence under the EP Act. It may amount to a breach of a person's environmental duty under section 25 of the EP Act and, in limited circumstances, may amount to an environmental nuisance under the EP Act (which gives rise to the considerations outlined above). A breach of the environmental duty does not necessarily amount to an offence under the EP Act, even though compliance with the duty may be enforced by the issue of an environment protection order. 2.1.18 Importantly, enforcement of nuisances caused by bird scaring devices in sole reliance upon the Noise Policy and EP Act is contingent upon a noise emission from a bird scaring device amounting to "pollution" as defined under the EP Act. From an evidentiary perspective, this can be difficult to prove. For this reason, the EP Act does not provide an alternative practical and effective means to address these nuisances. 2.1.19 Where Councils consider (having regard to the views of the community) that bird scaring devices cause a nuisance (consistent with the ordinary meaning of the word) and, it is in the interests of the community to regulate such devices in order to prevent that nuisance, it is necessary and appropriate for the nuisance by-law making power to be retained for this purpose. Horses and Other Animals on Streets and Roads As previously expressed, the by-law making powers under sections 667(1).5 and 667(1).7 are no longer utilised by Councils and are redundant. Accordingly, I do not foresee any issue with the repeal of these provisions. 4. 5. 4 Good Rule and Government 4.1. This by-law making power is to be construed against (and is limited by) Councils' by-law making powers under section 238 and 239 of 1999 Act and section 90 of the Dog and Cat Management Act 1995. 4.2. In our experience, Councils do not rely solely upon this power for making bylaws but, instead, in a non-specific manner to support the adoption of proposed by-laws. 4.3. I see no issue with the repeal of this provision. Preventing Obstruction of a Road or a Watercourse 5.1. A number of existing Roads By-laws adopted by Councils include a provision that prohibits, without the Council's permission, the erection, installation or placement of any structure, object or material that obstructs a road4. The power to include this provision within the Roads by-law is conferred by regulation 13(1) of the Local Government (Implementation) Regulations 1999. 5.2. I have noted OSLGR's view that section 221 of the 1999 Act may be relied upon to address obstructions on a road. This is the case only where the relevant obstruction can be classed as an 'alteration to a public road' under section 221(2)(b) of the 1999 Act. Section 221 is to be read in conjunction with section 234 of the 1999 Act, which authorises Councils to remove objects from See for example clause 7.4 of the LGA template Roads by-law, which has been adopted by a number of Councils. Document1 Ms A Malone -6- 9 February 2016 roads if the placement, installation or erection of the object has not been authorised by the Council (which will ordinarily be the case if it the object is an obstruction). However, whilst section 221 is an offence provision it is not an expiable provision meaning that enforcement may only occur through a full prosecution. Section 234 is not an offence provision. To that end, these provisions do not achieve the same effect as a by-law provision regulating obstructions to roads. 5.3. That said, section 235 of the 1999 Act, which is an expiable offence provision, may certainly assist where the obstruction is rubbish or 'goods, materials, earth, stone, gravel, or any other substance' that falls within the ambit of section 235(1)(b) of the 1999 Act. To the extent that section 235 enables Councils to effectively enforce obstructions on a road it renders the by-law making power superfluous. 5.4. Taking the above into account, my view is that sections 234 and 235 confer sufficient powers to enable a Council to remove (and adequately deal with) an obstruction on a road or watercourse. For this reason, I concur with OSLGR that regulation 13(1) of the Local Government (Implementation) Regulations 1999 may be permitted to expire. Conclusion For the reasons expressed above, there are grounds to retain the nuisance by-law making power which is reasonably relied upon by Councils. It is to be noted that the use of this power is limited by the by-law making provisions of the 1999 Act, which go some way to preventing against this power being used in an unreasonable manner. In relation to the remaining by-law making powers canvassed above, existing legislation is sufficient to address the matters that these powers are intended to address. Accordingly, the repeal/expiry of these provisions should not significantly impact or hamper a Council's regulatory functions. Please contact either me or Cimon Burke if you have any further questions. Yours sincerely WALLMANS LAWYERS MICHAEL KELLEDY Partner Direct Line: 08 8235 3091 Mobile: 0434 608 737 Email: michael.kelledy@wallmans.com.au Document1