Discussion Questions for Seminars, 18

advertisement

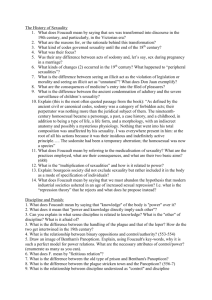

HIST 1017, Seminar Week 1 Sexuality as a category of historical analysis Starting in the 1990s the history of sexuality moved out of the margins and into the mainstream of history. Most of you students, then, have grown up in a world where few would question the value of sexuality as a category of historical analysis. In this week’s seminar we shall discuss how that shift happened, and some of the debates that continue about how we can study the history of sexuality. The first article this week (“Clio in Search of Eros)” is the introduction to a 2003 issue of one of the leading journals of American history, The William and Mary Quarterly, devoted completely to the theme of “sexuality in early America.” As such, the authors endeavor to point out how sexuality moved from the ‘entertainment’ section of the journal (the journal was founded in 1892) to its main pages as a serious area of study by the 1960s and 1970s. Note the emphasis the authors put on the influence of the French philosopher/historian Michel Foucault on historical works that have been produced in the last quarter century, by scholars who have either followed or fundamentally challenged his insights. Look carefully at the title of the article; if you don’t know who “Clio” and “Eros” are, so a little web research to find out. In other words, what does the title mean? Your main goal in reading this article is to get a sense of how the study of sexuality in American history has developed over the last twenty-five years. After reading the article you should be prepared to discuss the following question in seminar: What are the main themes, methods, and sources that the authors identify have been used by historians to study sexuality? The second article (“The Productive Hypothesis”) is more theoretical in nature (it appeared in the journal History and Theory after all). Ostensibly a critique of Foucault, the article does attempts to explain how Foucault’s works have challenged the way that historians think about sexuality, and offers her own insights on overcoming what she sees as the limitations of his methods. The language the author uses is quite dense and is peppered with a lot of critical theory jargon. Don’t worry if you don’t get it all … just try to work your way through. In short, what the author is trying to do is to show that Foucault was a product of his times, and from there to point to ways that historians can move beyond the Foucault paradigm. The real point the author is trying to emphasize is that the big omission in Foucault’s work was his “neglect” of the category of gender. Thus the big question we want to discuss in seminar is: Can there be something called the ‘history of sexuality’ without a discussion of gender, or as the author seemingly contends, are the categories of masculinity and femininity necessary foundations for a deeper understanding of the history of sexuality?