What is Life? Assignment

advertisement

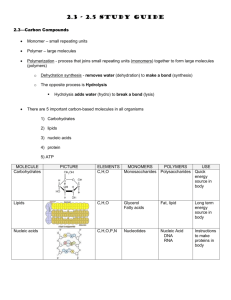

What is Life? Socratic Seminar Background Information: The Andromeda Strain is a science-fiction novel written by Michael Chrighton while he was attending Harvard Medical School. In the late 1960s, a secret military satellite contaminated with a microorganism crashes in an Arizona town, and the organism kills all but two of the town’s inhabitants—an elderly man and an infant. A research team of four scientists, all experts in their field, is called to Wildfire, a secret laboratory located beneath the desert in Nevada. The scientists work to discover how the microorganism killed the inhabitants of Piedmont, Arizona. They also discover why two people survived. They work scientifically to prevent the spread of the Andromeda strain, but their work is riddled with mistakes. The researchers struggle to understand the probable organism because it is so unfamiliar to them. Our definition of life is limited by our experiences that create a frame of reference. We define life based on the life that we have observed, but what if we discover new possible life forms that do not fit currently accepted descriptions of organisms? Would that mean that they are not living or that our definition of life is too narrow? Read the assigned passage from Michael Crighton's science fiction novel, The Andromeda Strain. Then, answer the close reading questions. Crighton, Michael. (1969). The Andromeda Strain (pp. 200-202). New York: Knopf. In another room, Leavitt was carefully feeding similar chips into a different machine, an aminoacid analyzer. As he did so, he smiled slightly to himself, for he could remember how it had been in the old days, before AA analysis was automatic. In the early fifties, the analysis of amino acids in a protein might take weeks, or even months. Sometimes it took years. Now it took hours – or at the very most, a day – and it was fully automatic. Amino acids were the building blocks of proteins. There were twenty known amino acids, each composed of a half-dozen molecules of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen. Proteins were made by stringing these amino acids together in a line, like a freight train. The order of stringing determined the nature of the protein – whether it was insulin, hemoglobin, or growth hormone. All proteins were composed of the same freight cars, the same units. Some proteins had more of one kind of car than another, or in a different order. But that was the only difference. The same amino acids, the same freight cars, existed in human proteins and flea proteins. That fact had taken approximately twenty years to discover. But what controlled the order of amino acids in the protein? The answer turned out to be DNA, the genetic-coding substance, which acted like a switching manager in a freightyard. That particular fact had taken another twenty years to discover. But then once the amino acids were strung together, they began to twist and coil upon themselves; the analogy became closer to a snake than a train. The manner of coiling was determined by the order of acids, and was quite specific: a protein had to be coiled in a certain way, and no other, or it failed to function. Another ten years. Rather odd, Leavitt thought. Hundreds of laboratories, thousands of workers throughout the world, all bent on discovering such essentially simple facts. It had all taken years and years, decades of patient effort. And now there was this machine. The machine would not, of course, give the precise order of amino acids. But it would give a rough percentage of composition: so much valine, so much arginine, so much cysteine and proline and leucine. And that, in turn, would give a great deal of information. Yet it was a shot in the dark, this machine. Because they had no reason to believe that either the rock or the green organism was composed even partially of proteins. True, every living thing on earth had at least some proteins – but that didn’t mean life elsewhere had to have it. For a moment, he tried to imagine life without proteins. It was almost impossible: on earth, proteins were part of the cell wall, and comprised all the enzymes known to man. And life without enzymes? Was that possible? He recalled the remark of George Thompson, the British biochemist, who had called enzymes “the matchmakers of life.” It was true; enzymes acted as catalysts for all chemical reactions, by providing a surface for two molecules to come together and react upon. There were hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of enzymes, each existing solely to aid a single chemical reaction. Without enzymes, there could be no chemical reactions. Without chemical reactions, there could be no life. Or could there? It was a long-standing problem. Early in planning Wildfire [a team designed to deal with extraterrestrial biological specimens on Earth], the question had been posed: How do you study a form of life totally unlike any you know? How would you even know it was alive? This was not an academic matter. Biology, as George Wald had said, was a unique science because it could not define its subject matter. Nobody had a definition for life. Nobody knew what it was, really. The old definition – an organism that showed ingestion, excretion, metabolism, reproduction, and so on – were worthless. One could always find exceptions. The group had finally concluded that energy conversion was the hallmark of life. All living organisms in some way took in energy – as food, or sunlight – and converted it to another form of energy, and put it to use. (Viruses were the exception to this rule, but the group was prepared to define viruses as nonliving). For the next meeting, Leavitt was asked to prepare a rebuttal to the definition. He pondered it for a week, and returned with three objects: a swatch of black cloth, a watch, and a piece of granite. He set them down before the group and said, “Gentlemen, I give you three living things.” He then challenged the team to prove that they were not living. He placed the black cloth in the sunlight; it became warm. This, he announced, was an example of energy conversion – radiant energy to heat. It was objected that this was merely passive energy absorption, not conversion. It was also objected that the conversion, if it could be called that, was not purposeful. It served no function. “How do you know it is not purposeful?” Leavitt had demanded. They then turned to the watch. Leavitt pointed to the radium dial, which glowed in the dark. Decay was taking place, and light was being produced. The men argued that this was merely release of potential energy held in unstable electron levels. But there was growing confusion; Leavitt was making his point. Finally, they came to the granite. “This is alive,” Leavitt said. “It is living, breathing, walking, and talking. Only we cannot see it, because it is happening too slowly. Rock has a lifespan of three billion years. We have a lifespan of sixty or seventy years. We cannot see what is happening to this rock for the same reason that we cannot make out the tune on a record being played at the rate of one revolution every century. And the rock, for its part, is not even aware of our existence because we are alive for only a brief instant of its lifespan. To it, we are like flashes in the dark.” He held up his watch. His point was clear enough, and they revised their thinking in one important aspect. They conceded that it was possible that they might not be able to analyze certain life forms. It was possible that they might not be able to make the slightest headway, the least beginning in such an analysis. The Andromeda Strain Close Reading Questions Each question must be answered by referring to the text. Write down the paragraph numbers that helped you in answering these questions. 1. Wildfire posed two questions. What two questions are posed? 2. Why are these difficult questions to answer? Which parts of the text help you answer this question? 3. According to biologists living organisms are characterized by seven signs of life: living things have highly organized, complex structures; living things maintain a chemical composition that is quite different from their surroundings; living things have the capacity to take in, transform, and use energy from the environment; living things can respond to stimuli; living things have the capacity to reproduce themselves; living things grow and develop; living things are well-suited to their environment. Which characteristics of life are considered to be worthless in the text? considered worthless according to the text? Why are they 4. What does the group consider to be the hallmark of life? What does an organism have to do to be considered alive according to the text? 5. Why might some scientists argue that viruses are living? 6. Read the last paragraph of the text again. Which events in the text lead the group to change their thinking? 7. Does Leavitt believe that cloth, watches, and granite are really organisms? Which parts of the text lead you to this conclusion and how did each part help you reach this conclusion? 8. What is the point that Leavitt is making? Which parts of the text lead you to this conclusion and how did each part help you to reach this conclusion?