Irish Immigration to the United States - Mr. Bergen

advertisement

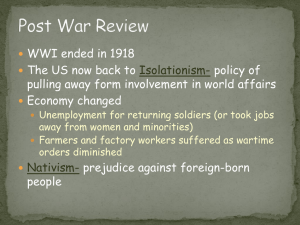

The Irish Waves of Irish Immigration Irish Immigration to the United States When were the major waves of immigrants from the Ireland to the United States? Throughout the first half of the 19th century, Irish immigrants were mostly Protestant and middle class tradesmen. There was also a significant minority of lower class Catholics that arrived to escape the dire socioeconomic conditions of Ireland. The Potato Famine of 1845-1851 caused many of the lower class Catholics of Ireland to immigrate. Huge influxes of Irish migrants, totaling around 1.7 million, immigrated from 1845 untill 1860. Irish immigration slowly declined during the late 19th century, and has been up and down throughout the 20th century. From which regions of Ireland did they leave? Early Protestant immigrants migrated mainly from the northern provinces of Ireland. Later Catholic immigrants came from the Southern provinces; examples include the counties of Connaught and Munster. Push Factors Early immigrants, of the middle class Protestant variety, immigrated for opportunity as tradesmen in the United States. The lower class Catholic immigrants immigrated to escape the pervasive economic hardship of Ireland. This was exacerbated by the Irish potato famine, in which almost 1.5 million Irish men and women died of starvation or disease. Pull Factors Early Protestant immigrants were drawn to the overwhelming Protestant majority of the United States. Catholic unskilled laborers found thriving American urban centers as a destination for their work. The textile and construction industries were specifically targeted for their high demand for unskilled workers. Where did they settle, and why? Most Irish immigrants settled in urban areas, whether they were the earlier Protestant or later Catholic newcomers. Destinations were primarily in the Northeast, such as Boston, New York and Philadelphia. Later, some settled as far as Chicago, New Orleans or San Francisco. Employment The unskilled Catholic workers of the early 19th century took up many different occupations: mining, canal and railroad construction, port working, textile mills, etc. After the Civil War, many of these workers moved up to more skilled positions as managers in their previous industries, along with police officers, post-office workers, and other civil servant jobs. The Irish continued to move up the occupational ladder throughout the 20th century, and are now immersed in almost every industry in America. The Irish played a prominent role in the labor movement and in early trade unions. Stereotypes, Discrimination, and Other Struggles Discrimination was prevalent for early Irish immigrants, almost exclusively centered on the later unskilled Catholic laborers. Much discrimination was religious, as America was a predominantly Protestant country throughout the 19th century and Catholics were looked down upon. The Irish were often portrayed as small pugnacious drunkards, and gave way to the terms “paddywagons”, “shenanigans” and “shanty Irish”. While these stereotypes have been overcome, there still exists sentiment that the Irish are close-minded, uneducated and fond of “hitting the bottle”. These presumptions are false, as many studies have shown that the Irish are among the most educated and most liberal demographics in the country. Assimilation The assimilation of Irish immigrants has been easier than most immigrants, due mostly to their ability to speak English and the similarities between Western European and American culture. While many hurtful stereotypes of Irish immigrants did exist throughout the 19th century, the Irish have overcome these and are now a proud part of American heritage. Some say that the Irish can owe part of their acceptance into the American mainstream to the Civil War, where they became renowned for their bravery and intense patriotism. Contributions to the United States Irish Americans have played a leading role in the labor and equality movement, and they include a founder of the American Federation of Labor, Peter James McGuire (known as the “Father of Labor Day”, and a founder of the American Civil Liberties Union, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. They have also had a leading role in the arts. Examples include Mathew Brady, the trailblazing war photographer, the artist Georgia O’Keefe, novelists Edgar Allan Poe, F. Scott Fitzgerald and William F. Buckley. Irish Americans also include William Russell and Henry Ford, the founders of the Pony Express and Ford Motor Company, respectively. Irish Americans in the entertainment industry include John Wayne and Jack Nicholson. Two of the most influential Supreme Court Justices in recent years have been Irish: Sandra Day O’ Connor and William G. Brennan. By far, the most celebrated and beloved Irish American sports figure has been George Herman “Babe” Ruth. Interesting Facts about Irish Immigration The Irish fiddle has become an important influence on contemporary American country and folk music. Comparisons to Today's Immigration Debate Irish immigrants were mainly unskilled workers who lived in large urban areas and were discriminated under false prejudices that they were small and lazy drunkards who stole jobs from Protestant Americans. The Chinese If not to count the ancestors of the Amerindians who presumably crossed the Bering Strait in prehistoric times, the Chinese were the first Asians immigrants to enter the United States. The first documentation of the Chinese in the U.S. begins in the 18th century, however, there have been claims stating that they were in the area now known as America at an even earlier date. Large-scale immigration began in the mid 1800's due to the California Gold Rush. Despite the flood of Chinese immigrants during that time, their population began to fall drastically. Because of laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, the highly imbalanced male to female ratio, and the thousands of immigrants returning back to China, the Chinese population in the U.S. fell to a lowly 62,000 people in 1920. Nonetheless, the Chinese make up the largest Asian population in the United States today. In actuality, the first Chinese immigrants were well and widely received by the Americans. However, the first Chinese immigrants were wealthy, successful merchants, along with skilled artisans, fishermen, and hotel and restaurant owners. For the first few years they were greatly receipted by the public, government officials, and especially by employers, for they were renowned for their hard work and dependability. However, after a much larger group of coolies, unskilled laborers usually working for very little pay, migrated to the U.S. in the mid 1800's, American attitudes became negative and hostile. By the year 1851, there were 25,000 Chinese working in California, mostly centered in and out of the "Gold Rush" area and around San Francisco. During that time, more than half the Chinese in the U.S. lived in that region. These Chinese clustered into groups, working hard and living frugally. As the populations of these groups increased, they formed large cities of ethnic enclaves called "Chinatowns" all over the country. The first and most important of the Chinatowns, without a doubt, belonged to San Francisco. One of the most remarkable qualities of San Francisco's Chinatown is its geographic stability. It has endured half a century of earthquakes, fires, and urban renewal, yet has remained in the same neighborhood with the same rich culture. Chinatowns have traditionally been the places where Chinese Americans lived, worked, shopped, and socialized. Although these cities were often overcrowded slum areas in the 1800's, the Chinatowns turned from crime and drug ridden places to quiet, colorful tourist attractions in the mid 1900's. The way of living among the Chinese was quite dissimilar from the patterns displayed among the masses of rowdy American gold-seekers surrounding them. Approximately 1/3 of the of the men attracted by California gold were Southern whites. Along with desires of wealth, many Southerns brought along hostile racial attitudes from the antebellum South. In the years that followed, those virulent temperaments were felt through laws and attitudes, and Blacks as well as Chinese suffered throughout the mid-century. Miners in the area often used violence to drive the Chinese out of various mines. While impatient gold-seekers would abandon prospective rivers, the Chinese would remain, painstakingly panning through the dust to find bits of gold. The Chinese did not only mine for gold, but took on jobs such as cooks, peddlers, and storekeepers. In the first decade after the discovery of gold, many had taken jobs nobody else wanted or that were considered too dirty. However, in 1870, hasty exploitation of gold mines and a lack of well-paying jobs for non-Asians spurred sentiment that the "riceeaters" were to blame. By 1880, a fifth were engaged mining, another fifth in agriculture, a seventh in manufacturing, an added seventh were domestic servants, and a tenth were laundry workers. Approximately 30,000 Chinese worked outside of California in such trades as mining, common labor, and service trades. During the 1860's, 10,000 Chinese were said to be involved in the building of the western leg of the Central Pacific Railroad. The average railroad payroll for the Chinese was $35 per month. The cost of food was approximately $15 to $18 per month, plus the railroad provided shelter for workers. Therefore, a fugal man could net about $20 every month. Despite the nice pay, the work was backbreaking and highly dangerous. Over a thousand Chinese had their bones shipped back to China to be buried. Also, although nine-tenths of the railroad workers were Chinese, the famous photographs taken at Promontory Point where the golden stake was driven in connecting the east and west by railway, included no Chinese workers. As time passed, the resentment against the Chinese increased from those who could not compete with them. Acts of violence against the Chinese continued for decades, mostly from white urban and agricultural workers. In 1862 alone, eighty-eight Chinese were reported murdered. Though large landowners that hired Chinese, railroads and other large white-owned businesses, and Chinese workers themselves pushed against a growing anti-Chinese legislation, the forces opposing the Chinese prevailed, issuing laws that excluded or harassed them from industry after industry. Mob violence steadily increased against the Chinese until even employers were at risk. Eventually, laws such the Naturalization Act of 1870 and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 restricted immigration of Chinese immigrants into the U.S. The Naturalization Act of 1870 restricted all immigration into the U.S. to only "white persons and persons of African descent," meaning that all Chinese were placed in a different category, a category that placed them as ineligible for citizenship from that time till 1943. Also, this law was the first significant bar on free immigration in American history, making the Chinese the only culture to be prohibited to freely migrate to the United States for a time. Even before the act of 1870, Congress had passed a law forbidding American vessels to transport Chinese immigrants to the U.S. The reason behind the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was to prevent an excess of cheap labor. However, the act froze the population of the Chinese community leaving its already unproportional sex ratio highly imbalanced. In 1860, the sex ratio of males to females was already 19:1. In 1890, the ratio widened to 27:1. For more than half a century, the Chinese lived in, essentially, a bachelor society where the old men always outnumbered the young. In order to sustain their population after the Chinese Exclusion Act, there was an immeasurable amount of illegal immigration. Plus, the Chinese had created an intricate system of immigration fraud known as "paper sons." Despite the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Chinese population in the United States continued to increase. Although, after the population reached its peak in 1890 with 107,488 people, the Chinese population began its steady decline. These descending numbers reflected not only the severing effect of the legislation on the inflow of Chinese immigrants, but of the many returning back to China due to the highly imbalanced sex ratio and to bring back monetary support for their families. In fact, many of the Chinese immigrants who migrated to the United States had no intention of permanent residency in the country. These sojourners preferred to retain as much of their culture as possible. As decades passed, the situation between the Chinese and the Americas improved. Such events as the Chinatowns turning from crime and drug ridden places to quiet, colorful tourist attractions, well-behaved and school conscientious Chinese children being welcomed by public school teachers, and China becoming allies with the U.S. during World War II, all paved the way for the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act. As immigration from China resumed, mostly female immigrants came, many, wives of Chinese men in the U.S. Many couples were reunited after decades apart. "I work on four-mou land [less than one acre, a larger than average holding] year in and year out, from dawn to dusk, but after taxes and providing for your own needs, I make $20 a year. You make that much in one day. No matter how much it cost to get there, or how hard the work is, America is still better than this." Italian Immigrants 75% of the Italian Immigrants to the U.S. came from Southern Italy. 4.5 million arrived in the U.S. between 1876-1924 2 million of them came between 1901-1910 Southern Italy was economically depressed and predominantly agricultural compared to the prosperous, cosmopolitan Northern region. The residents of Southern Italy were poor and worked as artisans, sharecroppers and farm laborers. Push Factors Southern and Northern Italy unified during the 1860's. The unification was disasterous for the South since the new constitution favored the North. At the same time that Italy was struggling economically, the population skyrocketed. In 1861 the population was 25 million. By 1901 it had grown to 33 million and by 1911 it had soared to 35 million even though many Italians had already emigrated. Where Italian Immigrants Settled More than 90% of the Italian immigrants settled in only 11 states: New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, California, Connecticut, Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, Missouri, and Louisiana. The Mid-Atlantic region and New England states attracted the majority of the Italian immigrants. 90% of Italian immigrants settled in urban areas. Pull Factors In the U.S. there were opportunities for "sojourners" or temporary migrants who found immediate employment, saved as much as possible and quickly returned home to Italy. (At least half of the Italian immigrants returned to Italy.) The sojourners made multiple trips and did not establish strong ties in the U.S. After 1910 women and families emigrated as well. Family reunification was a key pull factor by then. Housing Many Italian immigrants settled in communities, known as "Little Italies" with other immigrants from their country and region as a result of hostility that they faced from other more established Americans. Italian immigrants faced discrimination in housing. Victims of Discrimination Americans viewed Italian immigrants as a despised minority because they were perceived to be: Working class Seemingly resistant to assimilation Clannish Poor Illiterate Had high rates of disease Criminals Few European immigrant groups have faced as much ethnic prejudice as Italians. Epithets such as “wop,” “dago,” and even “Eye-talian” have been only surface manifestations of anti-Italian sentiments. The popular tendency to associate Italians with the Mafia and other criminal elements was long widespread. The federal Immigration Act of 1924 limited the number of southern and eastern Europeans who could migrate to the United States. The measure can be seen as at least partly motivated by anti-Italian sentiment. The conviction of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti for robbery and murder in 1927 has often been cited as an example of anti-Italian xenophobia because the evidence used against them was weak. Their long trial process was highly politicized. Instead of concentrating on the evidence concerning the crimes of robbery and murder, the trial focused on the defendants’ anarchist political views, which probably played a greater role in their conviction and eventual execution than the actual evidence in their case. As time passed and Italians moved into the American cultural mainstream, groups such as the Italian American Civil Rights League (formerly the Italian American Anti-Defamation League) and the National ItalianAmerican Foundation worked to combat negative stereotypes. The fact that criminals in films and television dramas often had Italian surnames contributed to the stereotypes. However, the Godfather films that seemed to romanticize the Mafia also made the American public more aware of the warmth of Italian family life and family values. By the early twenty-first century, stereotyping of Italians was declining, even though the popular cable television series The Sopranos was keeping alive public perceptions of criminal Italians. The Germans German Immigration to the United States When were the major waves of immigrants from Germany to the United States? Before the major waves of German immigration began, already 8.6% of the population was German. Many had immigrated to Pennsylvania seeking religious freedom or had come under the redemptioner system. German peasants would receive free passage to America but would be required to work for a businessman for 4-7 years to repay the cost of the voyage. 1850's - Nearly 1 million Germans immigrated to the United States. 1870's - 723,000 Germans immigrated to the United States. 1880's - 1,445,000 Germans immigrated to the United States. From which regions of Germany did they leave? In the 1850's small farmers and their families left southwestern Germany. Soon after, artisans and manufacturers left the central states of Germany. Later waves were made up of day laborers and agricultural workers from the rural northeast. Push Factors After the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815 the German economy was suffering. Foreign imports (especially cloth from England) flooded the German markets and German industry could not compete. In addition inheritance tradition of dividing farms among families was making farms so small that they were unsuccessful. The population had grown very large and was dependent on the potato to sustain it. In 1840 rural Germany was struck by the potato blight which led to famine. German princes sponsored societies (in the 1830's and 40's) that provided one way tickets to the poor with the idea that in the long run it was cheaper than long-term subsidies. A bestselling book in 1829 about Missouri by Gottfried Duden inspired a tidal wave of emigration. Social and economic discrimination in Germany led to the emigration of thousands of German Jews during all the immigration waves and Catholics after the May Laws of the 1870's. During several of the immigration waves, young men emigrated to escape being conscripted in the German (Prussian) military service. Pull Factors Aid societies promoted immigration by supporting bettering the conditions of immigrants The north-central states (Wisconsin, Minnesota and Michegan) promoted their states for settlement among Germans with funding and support from their state legislatures. The transcontinental railroads sent agents to ports of departure and arrival to recruit immigrants to take up their land grants or ship their goods through their freight lines. Chain migration occurred during the later phases of German immigration as newcomers joined family and friends who had made the journey before them, Where did they settle, and why? German Americans are most densely settled in the traditional "German belt" of Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, Nebraska and Iowa. One settlement pattern was named the "German triangle" from Saint Paul to St. Louis and Cincinnati incorporating other cities of German settlement: Chicago, Milwaukee, Indianapolis, Fort Wayne and Davenport. Germans had an important role in the cotton trade based in Louisiana so many arrived in New Orleans and made their way up the Mississippi, Ohio and Missouri rivers. Early German immigrants arrived in the port of Philadelphia and many chose to settle in Pennsylvania. Many who arrived in New York traveled the Erie Channel and the Great Lakes to the Midwest. The section on Pull factors will indicate other reasons why The German Belt consisted of the above mentioned states. Housing Homeownership was valued highly among German immigrants and they purchased homes as soon as possible and preferred homes made of brick. Employment Occupations dominated by Germans included baking, carpentry and brewing. They were also laborers, farmers, musicians and merchants. Many German immigrants had an agricultural background and also farmed in the United States. The entire family (often large) worked the farm. Small family operated businesses were also common for German immigrants. Children left school at a young age. Boys helped with the family business and girls worked as domestic servants. German women who were employed outside of the home, farm or family business did not tend to work in factories. Rather they labored in janitorial or service industries. Their involvement in labor unions helped German immigrants achieve better working conditions and they formed networks with workers of other backgrounds. Assimilation German immigrants assimilated more slowly than other immigrants due to their high numbers within the population. Also their basic needs - churches, schools, businesses, and stores - could be met within the German immigrant community. Therefore interaction with the native-born community was not as urgent. Stereotypes, Discrimination, and Other Struggles The popular culture presents a sterotyped view of Germans as either brutal or jolly, overwheight and beerguzzling. German culture is portrayed very narrowly and only represents one region of Germany - Bavaria where the capital Munich is located. The typical traditional costume of that region is the lederhosen (short pants with suspenders) and dirndl (full skirt) which has come to symbolize all of Germany. Contributions to the United States The German Christmas was the base for many of the American Christmas traditions including the giving of gifts, the Christmas tree and the emphasis on family. The labor movement was made strong by the particpation of many German immigrants. Albert Einstein, the prominent scientist in the field of physics and atomic energy in particular, was an immigrant from Germany. Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig were both baseball legends and sons of German immigrants. Interesting Facts to Compare to Today's Immigration Debate From 1850-1870 German was the most widely used language in the United States after English. Germans sought to maintain the German language through establishing German language schools. In 1881 approximately 1 million children were attending schools with all or part of the curriculum taught in German .(42% of that total were being educated in the public school system.) Norwegians Norwegian Immigration to the United States When were the major waves of immigrants from Norway to the United States? 1825 is recoginized as the start of Norwegian emigration, when the ship Restauration set sail to the U.S. with 53 Norwegians aboard. However, it was not until 1865, the end of the Civil War, that a large Norwegian immigration occured, a mass immgration that lasted for eight years. During this time period, 110,000 Norwegians entered the United States. A second and larger wave of mass immigration took place from 1880 to 1893. Prior to 1880, the majority of immigrants migrated with their families, and in 1880 that changed. Immigrants were younger, educated, and moving without their family. 800,000 Norwegians immigrated in total, 1/3rd of Norway’s whole population 1825-1925 From which regions of Norway did they leave? The first Norwegian immigrants left their homes in rural areas of western and eastern Norway. Push Factors The first immigrants, who were mainly Lutheran pietists and Quakers, came to the U.S. to avoid religioius persecution. In the 1800s, Norway faced an industrial slowdown, which made it hard for the younger population to find jobs, and they left in search of a way to support themselves and their families. Pull Factors While Norway had a shortage of jobs in the 1800s, America had a shortage of labor. As America's economy grew, more workers were needed. This opportunity for employment drew many Norwegian emigrants to America. Where did they settle, and why? The early immigrants, the Lutheran pietists and Quakers with the help of American Quakers settled in western New York. From there, the Norwegians began to move westward, finding Norwegian settlements along the way, first in Illinois and then in Wisconsin and Minnesota. From the mid 1800s to the early 1900s, the majority of Norwegian immigrants lived in the upper Midwest (Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, and the Dakotas). Norwegian communities, also developed in Seattle, Brooklyn, New York, Alaska and Texas. As of 1990, the largest populations of Norwegian Americans lived in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Housing In the 19th century, many lived in small communities, usually farming communities. In 1900, almost 75 percent of Norwegians lived in towns populated with less than 25,000 people. In addition to living farming communities, Norwegians could also be found in enclaves of major cities, such as Seattle and Minneapolis. Although, the Norwegian communities have since disappeared as the Norwegians became more assimilated. Starting in the 1920s more Norwegians began moving from rural areas into suburban ones. Employment When the Norwegians emigrated to the U.S. during the 1800s, they brought their traditions with them. One of these traditions was farming. Many Norwegian immigrants made a living as farmers, growing such crops as wheat and corn and raising cattle and hogs. In 1900, nearly 54 percent of Norwegian children came from farming families. It was also common for other Norwegian and Scandinavian men to work in the construction, logging, and shipping industries. While the men worked in physical occupations, women at the time, worked as domestic or personal servants. Currently, access to higher education has broadened the occupational fields for Norwegian-Americans and they are not over-represented in any particular field. Assimilation By living in farming communities and in enclaves, the Norwegians found people who shared their culture, values, and homeland. While this may have offered some comfort for the immigrants, it also segregated them from American society. However, when it became necessary to interact outside their communities to run their farms, Norwegians began to develop relations with the larger American society. Stereotypes, Discrimination, and Other Struggles While Norwegian immigrants did not face strong anti-immigrant sentiment, they were the targets of some unfriendly remarks. Sometimes they were called "guests," a label signifying that the Norwegians were not part of America and implied that they would eventually leave. Contributions to the United States Traditional Norewegian foods that have survived or have been reintroduced as part of Norwegian-American ethnic heritage are lutefisk and lefse. Lutefisk is a dried Norwegian cod soaked in a lye solution and lefse is a thin buttered pancake made from a rolled dough. Polish Immigrants Polish Immigration to the United States When was the largest wave of immigrants from Poland to the United States? 1921-1950 and 1981-Today Officially, more than 1.5 million Polish immigrants were processed at Ellis Island, between 1899 and 1931 Push Factors Before these larger waves, Polish immigrants came to the United States looking for a better life. Most Polish immigrants to the United States were agrarian and unskilled laborers, and they came from a country that had been occupied by outside forces up until 1919. Many could no longer survive in Poland because their country had not yet modernized its agricultural methods or industries and could not compete with the more industrialized countries in Western Europe. Also, at this time.60% of the land was owned by only 2% of the population, signifying that the average Pole did not have a lot of opportunities to advance himself in the agricultural sector. After World War I and during the reign of communism in Poland, political refugees fled the country seeking freedom, first from an occupation by Germany and then from communism. Pull Factors For many Polish immigrants, the United States held the promise of a better life. The United States was a growing country in need of labor to expand, and Polish immigrants provided some of that labor, especially in the growing milling and slaughterhouse industries in the Upper-Midwest. After World War II, because the United States stood so strongly against communism and the USSR spehre of influence, it attracted political refugees from communist countries in Eastern Europe such as Poland. Where did they settle, and why? The first official Polish-American settlement and independent Polish Catholic church was in Panna Maria, TX, but large pockets of Polish immigrants settled in Upper-Midwestern cities, such as Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Omaha, St. Louis, and especially Chicago. They worked in mills and slaughterhouses in these growing cities. Stereotypes, Discrimination, and Other Struggles There were many stereotypes associated with Poles in the United States. The “Polish Joke” said that all Poles were slow, stupid, undependable, volatile drunkards. When Poles first settled in the United States, they were accused of not wanting to assimilate, holding closely to their language, culture, and religion. In reality, many Polish immigrants could not wait to become Americans, and stereotypes around being Polish caused them shame. As one daughter of a Polish immigrant puts it, We wanted to be Americans so quickly that we were embarrassed if our parents couldn’t speak English. My father was reading a Polish paper. And somebody was supposed to come to the house. I remember sticking it under something. We were that ashamed of being foreign (Gale 1449). Poles were also accused of ruining the economy because they send money back to Poland to support family members. As one author puts it, “The amount of money Polish workers sent overseas eventually became so large that it worried both American and European authorities” (Harvard 797). In 1910 alone, $40 million was sent back to Poland. Occupations Polish-American grocery, 1922, Detroit, Michigan. Lopata (1976) argues that Poles differed from most ethnics in America, in several ways. First, they did not plan to remain permanently and become "Americanized". Instead, they came temporarily, to earn money, invest, and wait for the right opportunity to return. Their intention was to ensure for themselves a desirable social status in the old world. However, many of the temporary migrants had decided to become permanent Americans. Following World War I, the reborn Polish state began the process of economic recovery and many Poles tried to return. Since all the ills of life in Poland could be blamed on foreign occupation, the migrants did not resent the Polish upper classes. Their relation with the mother country was generally more positive than among migrants of other European countries. It is estimated that 30% of the Polish emigrants from lands occupied by the Russian Empire returned home. The return rate for non-Jews was closer to 50–60%. More than two-thirds of emigrants from Polish Galicia (freed from under the Austrian occupation) also returned. American employers considered Polish immigrants better suited than Italians, for arduous manual labor in coal-mines, slaughterhouses and steel mills, particularly in the primary stages of steel manufacture. Consequently, Polish migrants were recruited for work in the coal mines of Pennsylvania and the heavy industries (steel mills, iron foundries, slaughterhouses, oil and sugar refineries), of the Great Lakes cities of Chicago, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Buffalo, Milwaukee and Cleveland. Contribution to the United States: Famous Poles Polish-Americans have influenced American culture in many ways. Most prominent among these is through the inclusion of traditional Polish cuisine such as pierogi, kielbasa, golabki. Some of these Polish foods were tweaked and reinvented in the new American environment such as Chicago's Maxwell Street Polish Sausage. Polish Americans have also contributed to altering the physical landscape of the cities they have inhabited, erecting monuments to Polish-American heroes such as Kościuszko and Pulaski. Distinctive cultural phenomena such as Polish flats or the Polish Cathedral style of architecture became part and parcel of the areas where Polish settlement occurred. Poles cultural ties to Roman Catholicism has also influenced the adoption of such distinctive rites like the blessing of the baskets before Easter in many areas of the United States by fellow Roman Catholics. Liberace (full name Wladzic Valentino Liberace) – half-Polish and half-Italian singer Henry and Jack Warner – co-founders of Warner Bros, Inc. Mike Ditka – Football coach of the Chicago Bears. Vietnamese Vietnamese Immigration to the United States When were the major waves of immigrants from Vietnam to the United States? Before 1975, there were almost no Vietnamese living in the United States. In 1975, a group of 125,000 refugees came to the United States from Vietnam. These were people who had close ties with the toppling South Vietnamese government and were largely skilled profesionals. In the two year after the first wave, numbers of refugees remained low, in the few thousands in the years soon after. However, in 1978 they began to grow, and in 1979 yet another wave of Vietnamese immigrants came to the United States. This wave continued and grew in 1980 and 1981 when when almost 200,000 Vietnamese immigrated Immigration from Vietnam declined greatly following 1981 but remained constant, with about 24,000 immigrants a year until 1986 The United States created a program in the 1980s called the Orderly Departure Program which allowed people who were interviewed and approved by the U.S. to immigrate to the United States. Push Factors Instability that was created by the Vietnam war was the primary reason for immigration to the United States. The South Vietnamese government was unprepared for war and after the United States withdrew, it was toppled by North Vietnam and the National Liberation Front. Vietnamese with ties to the South Vietnamese government came as refugees to avoid being killed or oppressed. The second wave of immigration was a result of the poor political and economic situation in Vietnam. In 1979, Vietname invaded Cambodia and a war broke out between China and Vietnam, leading to further immigration. Pull Factors A large number of immigrants came as refugees fleeing persecution in Vietnam The United States had supported South Vietnam and accepted refugees who were closely tied to the South Vietnamese government and the American military. The United States created camps to recieve refugees and help resettle them. They were given living quarters and medical attention and were assigned to sponsors who would take responsibility for them. The United States was one country that openly accepted the Vietnamese, who were often poorly recieved in other countries. Greater economic and social stability was a major attraction for immigrants to the United States, as they could have greater freedom and more opportunities. Where did they settle, and why? Vietnamese immigrants settled primarily in warm areas. In 1984, over 40% of Vietnamese refugees lived in California. Texas was also a popular destination, and 7.2% lived there. In 1990, the census showed that 50% of Vietnamese lived in California and 11% in Texas, indicating that there was a certain value placed on living near other immigrants. Many Vietnamese Americans also lived in Virginia, Washington, Florida, New York, Lousiana, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. Housing The Vietnamese idea of a family encompasses not only parents and children, but grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins as well. Family ties are very important, and even though many families live independently, they often remain close to their parents. Vietnamese families settle both in the suburbs and in urban areas. Vietnamese Americans have larger families that Americans, with about 4.36 people per family as apposed to 3 in American families. Employment Vietnamese Americans are highly represented in technical jobs like machinery assembling and electrical engineering. However, there are no distinct patterns and they are involved in amlost every field. In southern states, Vietnamese Americans support the fishing industry by being fishers and shrimpers. Vietnamese immigrants have high employment rates, with an umeployment rate between 5 and 6 percent. Approximately 10% of Vietnamese Americans were self-employed in 1990. Vietnamese businesses are growing rapidly, showing Vietnamese ambition and dedication to succeeding. A number of Vietnamese American young men have begun enlisting in the U.S. army and have recieved much public attention. Education is valued in Vietnamese culture, and almost half of college age Vietnamese Americans are college students. Secondary education is encouraged for both men and women. Engineering is a popular field of interest for Vietnamese. Health care is also highly valued and being a doctor is very prestigious in the eyes of Vietnamese Americans. Stereotypes, Discrimination, and Other Struggles The information Americans have about Vietnamese people and Vietnam comes primarily from movies and books about the Vietnam war. Little attention is given to Vietnamese life and there is a focus on American involvement in Vietnam. Stereotypes about Vietnamese Americans are prevalent, and they are often viewed as overachievers who are very focused on school. There is also the belief that most Vietnamese are refugees. Many Vietnamese Americans have had difficulty due to discrmination, and almost 25% lived below the poverty line in 1990 Assimilation Vietnamese immigrants are very 'new'- only 18.6% of Vientamese in the United States were born here. However, by 1990, almost 75% of Vietnamese could speak english well or very well. A struggle that many Vietnamese families face is maintaining Vietnamese culture in the United States. Vietnamese Americans sometimes change their names to assimilate, but because Vietnamese are new immigrants, it is unclear if the culture is being lost. Most Vietnamese young people marry withing their ethnic group, but marriage to non-Vietnamese is not unheard of. Vietnamese culture values politeness in terms of interaction with others. Eye contact and disagreement is avoided. When second generation Vietnamese Americans shun these beliefs and accept more American behaviors, they are often viewed as disrespectful. Vietnamese immigrants have been highly succesful in terms of employment, and there is a low rate of umeployment. However, in 1990, almost a quarter of all Vietnamese were below the poverty line. In general, Vietnamese Americans are not very involved in American politics and government. There is great conflict within Vietnamese communities as to what the relationship between Vietnam and the United States should be. Some believe that any interaction between the two supports that socialist South Vietnamese government, others hope it will lead to economic benefits for Vietnam. On the whole, Vietnamese Americans are more concerned with political problems in Vietnam. Contributions to the United States Because the Vietnamese are new immigrants, there has not been much time for great contributions to be made to American society. Vietnamese fishers and shrimpers are important to the American fishing industry. Andrew Lam, an associate editor with the Pacific News Service, fled Vietnam with his family in 1975 and hsd published a number of essays and stories. He has written a memoir about life as a Vietnamese American. Dustin Nguyen, an actor, came to the United States from Vietnam as a 12 year old and became famous for his character on the T.V. series '21 Jump Steet'. Interesting Facts about Vietnamese Immigrants Politics, especially relating to Vietnam, are very important to Vietnamese Americans. In California, a Vietnamese business owner put up a picture of Ho Chi Minh, a Vietnamese communist, in his store. After words were exchanged between the business owner and a Vietnamese anti-communist group, protests began outside the store. A judge ordered that the owner had the right to display the picture, but a mob assaulted the owner. This shows how strongly many Vietnamese Americans feel about political issues pertaining to Vietnam. Comparisons to Today's Immigration Debate The second wave of Vietnamese immigrants consisted of people from rural backgrounds who did not have much education. They were primarily unskilled, and 'seem to be the least educated and skilled legal immigrants to the United States in recent history'. However, Vietnamese Americans are today are on the whole highly educated and employed and are great contributors to the United States. Mexicans The recent political sparring over immigration reform has included scant mention of cross-border diplomacy. Despite the growing interdependence of the U.S. and Mexican economies over the past few decades, the governments of the two nations have shown little interest in cooperating on the thorny issue of human migration. A brief look at the history of the Mexican-U.S. labor relationship reveals a pattern of mutual economic opportunism, with only rare moments of political negotiation. The first significant wave of Mexican workers coming into the United States began in the early years of the twentieth century, following the curtailment of Japanese immigration in 1907 and the consequent drying up of cheap Asian labor. The need for Mexican labor increased sharply when the Unites States entered World War I. The Mexican government agreed to export Mexican workers as contract laborers to enable American workers to fight overseas. After the war, an intensifying nativist climate led to restrictive quotas on immigration from Europe and to the creation of the U.S. Border Patrol, aimed at cutting back the flow of Mexicans. But economic demand for unskilled migrant workers continued throughout the Roaring Twenties, encouraging Mexican immigrants to cross the border—legally or not. A 43-year-old migrant worker picking strawberries in Florida, 1997. Migrants have long called strawberries frutas del diablo (fruits of the devil) because picking them ranks among the lowest-paid, most labor-intensive types of farm work. The Depression brought a temporary halt to the flow of Mexican labor. During the early 1930s, Mexican workers—including many legal residents—were rounded up and deported en masse by federal authorities in cooperation with state and local officials. Mexicans became the convenient scapegoats for widespread joblessness and budget shortages; as Douglas Massey, Jorge Durand, and Nolan J. Malone point out in Beyond Smoke and Mirrors (2002), Mexicans were accused, paradoxically, of both “taking away jobs from Americans” and “living off public relief.” The demand for Mexican immigrants reemerged after Pearl Harbor, when the U.S. government sought an agreement with Mexico to import large numbers of Mexican farm laborers. Known as braceros, these workers would ensure the continued production of the U.S. food supply during the war years. “It was Mexicans and Rosie the Riveter who ran the American economy and enabled American citizens to go to war,” explains vice provost for international affairs Jorge Domínguez, Madero professor of Mexican and Latin American politics and economics. Although intended as a wartime arrangement, the Bracero program continued under pressure from U.S. growers, who feared a continued labor shortage in the booming postwar economy. Still, the numbers of legal braceros fell short of demand, and growers began regularly recruiting undocumented workers to tend their fields. By the end of the Korean War, illegal immigration had become a fixture of the U.S. agricultural economy—and public sentiment had again turned restrictionist. In 1954, the U.S. government responded with “Operation Wetback,” apprehending close to one million illegal workers. Meanwhile, to appease the growers, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) reprocessed many of these undocumented Mexicans and returned them to the fields as legal braceros. In the early 1960s, with the advent of the civil-rights movement, public opinion began to view the Bracero system as exploitative and detrimental to the socioeconomic condition of Mexican Americans. The government ended the program in 1964. But growers were still hooked. “The problem of Mexican illegal immigration is born at the moment that the Bracero program ends,” Domínguez explains. “[Mexicans] keep coming, because the demand is still there.” Following the Hart-Celler Immigration Reform Act of 1965, which removed the racially based quotas on immigration set up in the 1920s, Mexicans for the first time had to compete for visas with immigrants from other areas of Latin America and the Caribbean. Rapid population growth and declining economic conditions in Mexico coincided with a reduction in the legal cap on Mexican immigration beginning in 1968, causing the numbers of undocumented workers to soar. As the problem of illegal immigration worsened through the recession-plagued 1970s, the prospect of diplomatic talks between Mexico and the United States grew less likely. The Mexican government saw little to gain from cross-border negotiations at a time when restrictionist voices in the United States were gaining ground. As Domínguez explains, “[The Mexican government] realized they had a stake in Mexicans going abroad, exporting the underemployment problem.” They also feared that any discussion with the United States would involve “linkage”—that is, that the United States would tie trade concessions to Mexico’s improved control of the border. This pattern of political avoidance continued into the 1980s. In 1986, when the United States passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), “there was no Mexican government voice in the process,” Domínguez points out. The passage of the IRCA set the stage, many observers believe, for the enormous and entrenched problem of undocumented immigrants that exists today. While granting amnesty to 2.3 million Mexicans residing illegally in the United States, the law began a process of border fortification and militarization that has had the opposite of its intended effect. The idea of building a wall—which began under the Clinton administration—turned a pattern of circular migration into one of permanent settlement. “Now ‘Once I make it, I’m not going back,’” Domínguez explains. As Princeton sociologist Douglas Massey pointed out to the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2005: “From 1965 to 1985, 85 percent of undocumented entries from Mexico were offset by departures and the net increase in the undocumented population was small. The build-up of enforcement resources at the border has not decreased the entry of migrants so much as discouraged their return home.” Ironically, while the ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994 heralded a new level of economic integration between Mexico and the United States, the question of labor migration remained off the table. “Even as binational trade with Mexico grew by a factor of eight from 1986 to the present,” Massey points out, “the Border Patrol’s enforcement budget has increased by a factor of 10 and the number of officers tripled. The U.S. Border Patrol is now the largest arms-bearing branch of the U.S. government save the military itself, with an annual budget of $1.4 billion.” In 2000, a year in which both countries elected new presidents, Mexico finally took the initiative to launch discussions on immigration. President George W. Bush seemed open to a policy along the lines of the Bracero agreement. “But the Mexicans overreached,” Domínguez explains. “They wanted to deal with everything, including the status of Mexicans already here.” The United States said no, and after 9/11, the Bush administration lost interest. The recent stalemate in the U.S. debate on immigration reform has stalled the possibility of diplomatic talks with Mexico, at least for now. The United States may have to resolve its internal contradictions on the subject of Mexican labor before any substantive cooperation with the Mexican government can take place. British immigrants Significance: As one of the earliest immigrant groups to North America, the British were responsible for some basic American cultural features, including language, laws, religion, education, and administration. They were also responsible for developing forms of trade and for creating strong American political and cultural links with Great Britain that have survived into the twenty-first century. British immigration to what is now the United States has run in an unbroken line from 1607 into the twenty-first century. However, it has gone through major transformations over the centuries: The earliest British settlers were the first major immigration group, imposing their culture on newly settled territory; modern British immigrants have become an almost invisible group, whose members assimilate quickly into American culture. Never been culturally homogeneous, British immigrants have been made up of several subgroups. Scotland remained a separate country for the first hundred years of British immigration, and Scottish immigrants developed their own distinctive patterns. In contrast, what is now the independent nation of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom until the early twentieth century, and its immigrants also developed their own immigration patterns, which should be considered separately. EvenWelsh immigration had somewhat different features, though statistically these are much more difficult to disentangle from the predominant English patterns. Virginia Colonies The first phase of British—mainly English—- settlement in the North American colonies was centered on Virginia and New England, to be followed by Maryland, the Carolinas, and Pennsylvania. After the transfer of the Dutch colonies to British rule, British immigration developed in New York, New Jersey, and Delaware. Lastly came the Georgia settlement. British emigration was not confined to the colonies that would later become the United States, however. Scottish immigration to Nova Scotia (New Scotland) was attempted in the face of French opposition. The main colonies of Virginia and New England developed quite differently in that they attracted very different types of immigrants. The first settlement that became permanent was founded in 1607 in the Jamestown area of Virginia. This was overseen by the Virginia Company of London, and was largely a commercial venture. In the hope of earning quick profits, many settlers who had little experience in farming or building came to Virginia. To these were added convicts whose sentences were commuted to “transportation.” Had it not been for a few determined leaders, such as Captain John Smith, the Virginia colony would have foundered on several occasions because of rampant sickness, company inefficiency, and an Indian massacre. After the company finally went bankrupt in 1624, the English crown took over the running of the colony directly. Meanwhile, new immigrants kept coming. The indenture system was instituted in which young men and women effectively sold themselves into servitude for fixed periods, at the end of which their masters were to give them capital and, at first, some land. Tobacco became the colony’s dominant crop. New England Colonies In contrast, British colonies in New England were founded by more principled immigrants, many of whom left England for religious reasons. The “Pilgrim fathers,” landing under the aegis of the Plymouth Bay Company, were basically nonconformists, that is, believing in the separation of church (especially the Church of England) and state. The Puritans, who held for radical reform of the Church of England, settled to the north around Salem and then Boston, under the aegis of the Massachusetts Bay Company and the Council for New England. In practical and organizational terms, these settlers were highly self-sufficient and quickly began making commercial profits through fishing and furs, then lumber products and even staple foodstuffs. As their settlements developed, they chose to sever as many ties with England as they could, at least until the 1640’s, when the Puritan Revolution launched the two-decade Commonwealth era in England. They created their own legal and electoral systems. They were fortunate to have a continuity of good leadership under men such as John Winthrop. Even so, the colonies’ growth was slow, with deaths through disease common and many settlers returning to England. In 1640, it is estimated that Massachusetts had only 14,000 English settlers; Virginia had 8,000, and Connecticut, Maryland, and New Hampshire each had fewer than 2,000. By 1660, Boston had no more than 3,000 inhabitants and Virginia’s towns even fewer. Backcountry settlements stretched barely one hundred miles inland from the coastal towns. Place-Names It generally falls to the first inhabitants of a land to name its features. Place-names consequently provide valuable evidence about the identities of early inhabitants and particularly whence they originated. Most place-names adopted by English settlers fall into four categories: Immigration from the United Kingdom, 1820-2008 names adapted from Native American forms names symbolizing their hopes and beliefs names honoring eminent persons, names borrowed from places in their original homeland Examples of place-names adapted from earlier Native American names include Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Susquehanna. Names expressing hopes and beliefs include Providence (divine guidance), Salem (peace), and Philadelphia (love). The many places honoring persons include Delaware and Baltimore (both aristocratic founders of colonies), Virginia (after the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I), and Charlotte, Charles Town, Charleston James Town, and Jamestown—all from British monarchs. New York was named after the duke of York, whose brother, King Charles II granted him the land taken from the original Dutch settlers. However, the fourth category—names borrowed from homelands—is most informative about the origins of the earliest British settlers. Nearly all such names in the early British colonies were taken from names of English places. Indeed, the very name “New England” suggests that a number of these places had the prefix “New.” Other examples include New London, New Shoreham, New Jersey, and New Hampshire. The majority of such borrowings, however, were simply the names that were used in England. The early settlers also brought their English county system with them and used distinctly English names for their new American counties. Many county names were borrowed from the names of counties in eastern England. These include Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Cambridge, Haverhill, Boston, and Yarmouth. Such county names are especially evident in the New England colonies. Other borrowings come from southwestern England: Bristol, Gloucester, Somerset, and Barnstaple—the later a major port of exit, as were Plymouth and Weymouth. Another major grouping of names comes from London and southeastern England. Examples include Middlesex, Surrey, Guildford (or Guilford), Hertford (or Hartford), Newhaven, Kent, Isle of Wight, Portsmouth, and Southampton. Other parts of England are also represented by county names such as Chester, Cheshire, Lancaster, and Manchester from the northwest; Cumberland and Westmorland from the north; Litchfield, Birmingham, and Stafford fromEngland’sWest Midlands. The absence of Scottish-derived place-names is significant. Welsh place-names are also rare, with only Bangor, Newport, and Swansea being well known. Welsh immigrants tended to prefer settling in colonies in the West Indies, and the Scots did not face the same religious pressures that drove the Puritans out of England. Only a few Scottish names in South Carolina suggest later immigration there. However, a cluster of Welsh names around Philadelphia suggests significant earlyWelsh settlement there. Examples of Welsh place-names in that region include Bryn Mawr, Haverford, Naberth, Berwyn, and Llanerch. Profile of British immigrants Immigrants who obtained legal permanent resident status in the United States, including people from England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. . Nineteenth Century Surge Precise U.S. immigration statistics began in 1830, making it easier to trace the pattern of British immigration from that date. Overall British immigration was not significant again until 1851. Figures for the years up to that date appear high only because they included Irish immigrants, who made up the bulk of the numbers. After midcentury, however, English immigration made up 10 percent of all European immigration into the United States, with Scottish immigration running at 9 percent of the English figures and Welsh at about 4 percent. Both figures conform with the overall composition of Great Britain’s population. About 250,000 English immigrated to the United States during the 1850’s. That figure grew to 644,680 during the peak decade of the 1880’s, when English immigrants constituted 13.6 percent of all European immigrants. No single destination attracted these new immigrants. The reasons behind the increased immigration rates lay in the huge growth of the British population, deteriorating urban conditions and a slowdown in Britain’s Industrial Revolution, which was being overtaken by those of Germany and France. Included in the figures for English immigrants were unknown numbers of Irish who moved on to the United States after first immigrating to England. Scottish Immigration The Scottish experience can be divided into two. The first arises out of the Scots being encouraged to emigrate to Ulster, in Northern Ireland, around 1611, to occupy land taken from the native Irish. These people became known as the Scotch- Irish, and their immigration to the Americas might best be regarded as part of Irish immigration. The second Scottish group were mainly Presbyterians. During the seventeenth century they enjoyed freedom of religion until the Restoration period after 1660. After that, they endured severe restrictions. However, as Canada came under British control, most Scottish emigrants preferred to go there, perhaps partly because Canada’s terrain resembled that of Scotland. There was, however, Scottish emigration as far south as the Carolinas. Extrapolations of data from the U.S. Census of 1790 suggest that overall Scottish immigration into the United States stood at 8 percent of the total population, with the heaviest groupings in Virginia, the Carolinas, and Pennsylvania. At the same time, Canada remained a popular destination for Scottish immigration, which was hastened by the Highland clearances during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. However, significant numbers continued to arrive in the United States. In fact, during the first decade of the twentieth century, when Scotland’s economy took a downturn, the 120,469 Scottish immigrants who entered the United States were represented almost one-third the 388,051 English immigrants who arrived during the same period. A peak period of Scottish immigration was during the 1920’s, when 159,781 Scots entered the United States; this number matched that of English immigrants during that decade. Modern Trends British immigration to the United States declined slowly during the early decades of the twentieth century at the same time immigration from southern and eastern Europe was increasing. More mindful of the needs of its own empire, Great Britain by then was sending large numbers of people to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. During the U.S. immigration-quota era that began during the 1920’s, the British quota was not always filled. A sudden surge of British immigration after World War II can be partly explained by the number of war brides who came to the United States. These women had met and married American servicemen stationed in the United Kingdom during the war. However, the more significant reason for the increased immigration was the great disparity in standards of living in postwar Britain and the United States. After World War II, the British once again saw America as a land of opportunity. However, as Britain’s own standard of living improved, emigration dropped of. By the 1970’s, only 2.7 percent of all immigrants entering the United States legally came from Great Britain. After the 1970’s, British immigration held steady at about 20,000 persons per year. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, 824,239 residents of the United States had been born in the United Kingdom, a figure that made the British the ninthlargest immigrant group. Most modern British immigrants have been professionals and skilled workers, including students, teachers and medical personnel, multinational employees, skilled construction workers, and spouses of Americans. British immigrants are nearly invisible in the United States, where they have assimilated quickly. With the growing ease of transatlantic travel, many British immigrants prefer to go back and forth between the United States and Britain instead of opting for American citizenship. In 2004, 139,000 British people entered the United States to become residents, but only 15,000 sought naturalization. Ethiopian immigrants Significance: After passage of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, Ethiopians became the third-largest national group of African immigrants to immigrate to the United States. Most arrived in the United States after Congress passed the Refugee Act of 1980. Ethiopia and its people have long held a special meaning in America. Once known as Abyssinia, Ethiopia stood for black pride and black independence as far back as the 1760’s. Already possessing strong biblical associations, the name “Ethiopia” became an iconic symbol of African independence throughout Europe’s twentieth century colonization of Africa. Some educated African American slaves such as the poets Phillis Wheatley and Jupiter Hammon occasionally identified themselves as “Ethiopians” during the era of the American Revolution. The tendency of black intellectuals to describe themselves as “Ethiopians” stems from the European custom—derived from biblical usage—of applying “Ethiopian” to all peoples from the African interior. This usage, which dates back to the ancient Greeks, can make it difficult to separate immigrants from the actual Northeast African nation of Ethiopia from the masses of African Americans. The first Ethiopian immigrants to reach North America probably arrived as slaves sometime during the seventeenth century. However, the bulk of voluntary immigrants to the United States came after 1974, when a repressive regime toppled the ancient monarchy and took control of the Ethiopian government. The ensuing exodus from Ethiopia, a landlocked nation on the northeastern Horn of Africa, resulted from political turmoil as well as famine and drought. Many refugees fled initially to settlement camps in the neighboring Sudan before moving on to the United States. Impoverished, the Sudan offered few economic opportunities, while the United States held out the hope of a prosperous future.Until Somalis surpassed them in 1994, Ethiopians were the largest group of Africans to immigrate under the provisions of the Refugee Act of 1980. Immigration from Ethiopia, 1930-2008 Source: Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, 2008. Figures include only immigrants who obtained legal permanent resident status. Ethiopian immigrants to the United States have differed from many other immigrant ethnic groups in that they typically arrived with a basic command of British English and tended to settle in disparate neighborhoods, instead of gathering in ethnic enclaves. The consequent lack of cohesive immigrant communities has complicated their efforts to maintain language and cultural ties to their homeland. Also, racism has been a new experience, with many exposed to the color line for the first time in the United States. Profile of Ethiopian immigrants Country of origin Ethiopia Primary language Amharic Primary regions of U.S. settlement Los Angeles, New York City, Denver, Minneapolis Earliest significant arrivals Seventeenth century Peak immigration period 1980’s Twenty-first century legal residents* 8,004 (1,000 per year) *Immigrants who obtained legal permanent resident status in the United States. Most Ethiopian immigrants are Coptic Christians and Muslims, and their religions have served as sources of comfort in the New World, with churches and mosques serving as community centers, health centers, and social services providers. During the early twenty-first century, the population of Ethiopia was almost evenly divided between Christians and Muslims, a split that is reflected among the immigrants to America. Ethiopia has also long had a significant Jewish population, but most of its Jews emigrated to Israel, while the bulk of other refugees fled to the United States. Ethiopians in America have subsequently established the Ethiopian Orthodox churches as well as the Bilal Ethiopian mosques.ETTLEMENT PATTERNS During the 1980s famine in Northern Africa and during the repressive Marxist rule, many Ethiopians migrated to Sudan. The majority of Ethiopians that ultimately migrated to the United States came from Khartoum, Sudan. The transitional resettlement period for Ethiopians in Sudan during this period was unpleasant for most. The majority of Ethiopians in Sudan were unemployed and relied on financial support from family members in Ethiopia or they lived in resettlement camps. Given the poor economic status of Sudan at the time, Ethiopian refugees would not fare well in the region. When the opportunity to resettle to a third country emerged, most Ethiopians targeted the United States. They believed that they would receive the greatest opportunity to improve their condition as previous refugees in North America had. When the nationalist wars in Ethiopia ended in 1991, much of the impetus for resettlement in the Horn of Africa was eliminated. However the defeat of the Derg led to violent upheaval in Southern Ethiopia which again instigated some displacement. When Ethiopian refugees arrived in the United States, their first inclination was to emigrate toward regions already heavily populated with Ethiopians. Many Ethiopians therefore targeted Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., Dallas, and New York City. Of these cities the metropolis that attracted the most Ethiopians in their secondary resettlement patterns was Washington, D.C. because of its large service sector economy. According to 1992 Office of Refugee Resettlement data, the majority of Ethiopians that were admitted to the U.S. were males (62 percent). The primary reason males far outnumbered females pertains to the patriarchal social structure that exists in many African countries. The social structure enabled men to meet the educational and occupational requirements established by the U.S. government for admittance into the United States. Another factor that related to admission was religion. The majority of Ethiopians admitted to the U.S. were Christian because they were considered the best candidates to easily assimilate into American culture. However the main factor that determined whether an Ethiopian immigrant could enter the United States was educational background. Because the Amharic-speaking Ethiopians had the greatest access to educational opportunities in Ethiopia they were the most heavily represented group of Ethiopians admitted to the U.S. in the 1990s. Acculturation and Assimilation According to a 1986 survey in The Economic and Social Adjustment of Non-Southeast Asian Refugees edited by Cichon et. al., assimilation into American culture has not been easy for Ethiopians. According to this study, Ethiopians have not adapted well to the fast pace and "fend for yourself" attitude inherent in an advanced capitalist society. This has resulted in an unusually high rate of suicide and depression. Many Ethiopian refugees have managed to find support in areas where there are higher concentrations of Ethiopians. Cities such as Washington, D.C. and Dallas, where previous generations of Ethiopians have established a social and economic foundation, facilitate the transition for incoming Ethiopians. There is also evidence in the same study to suggest that Ethiopians have greater success adapting to their new country when they gravitate to regions heavily populated with African Americans. Some of the activities Ethiopians engage in to strengthen their sense of belonging include playing soccer and joining social and economic support groups called Ekub. Traditionally, an Ekub was an Abyssintine financial group designed to make capital accessible and generate social activity. While some Ethiopians have penetrated middle class American society with little difficulty, others have relied on social organizations modeled after the social structure in their native land. Book Lakew, an Ethiopian scholar suggested that even though there are now generations of educated Ethiopians in the United States, they still suffer social and economic resistance in American society. Part of the problem, according to Lakew, is that Ethiopians lack valuable exposure to the team work, leadership, and organizational activities that many American children are trained to thrive in at an early age. Lakew claimed that groups like the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, and grade school mock elections provide American youth with the skills necessary to work in organizational settings later in life. The inability to flourish in an organizational setting, according to Lakew, prevents Ethiopian immigrants from making career advances in the United States. Lakew stated that this organizational handicap explains why Ethiopians rarely collaborate in business ventures in the United States, fail to form strong social and political organizations that promote the interests of Ethiopians in the United States, and lag behind other groups of immigrants who have graduated to the middle class in America.