The Winds of Words - Duplin County Schools

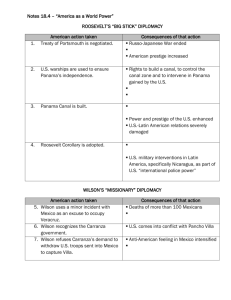

advertisement

"The Winds of Words" by George Will President Bush's policy toward Panama resembles Beethoven's Eroica played on a kazoo, a harmonica and a snare drum. The instruments are Inadequate to the large, swelling themes. U.S. goals are noble, the enemy of them is reptilian. U.S. rhetoric is alternatively soaring and excoriating. And General Noriega is unimpressed. Beethoven was stirred to compose the Eroica by the spectacle (which he soon came to despise) of Napoleon crashing around Europe making history; orphans and axioms, one of which is in vogue regarding Panama. Napoleon said: If you start to take Vienna-take Vienna. There is a time for tentativeness; power should not be used promiscuously; many undertakings are optional. But once they are undertaken, Impotence is unacceptable. Let us, as the lawyers say, stipulate this: Noriega is repulsive. However, until American power and prestige was engaged, it did not matter much, except to Panamanians, who governs Panama. If this were 1999, the eve of the transfer of control of the canal, it would be different. And the United States does have an interest in the proliferation of democracies, particularly in this hemisphere, especially in Central America. Political pluralism is a precondition for markets, modernity and progress. But among contemporary troublemakers, Noriega is small beer. While turning Lebanon into a charnel house, Syria's Assad still has time for terrorism against Americans. Kaddafi and his poison-gas facility are not disrupted by U.S. disapproval. Some of the people clamoring for the overthrow of Noriega favor normalization of relations with Castro. In "A Man for All Seasons," the bluff, unintellectual Duke of Norfolk cannot understand why his friend Thomas More refuses to take the oath the king demands derogating the pope's authority. Norfolk, exasperated by More risking his neck over what Norfolk considered theological nitpicking, exclaims, "Goddammit, man, it's disproportionate!" Most political mistakes involve some disproportion. It may have been a mistake to invest U.S. prestige in the dicey project of toppling Noriega with the winds of words. But Panama does get Americans excited. Strong passions about Panama contributed to the unmaking of a president. Reagan's 1976 campaign to wrest the Republican nomination from Ford was fading until Reagan stumbled upon the issue of the "giveaway of the canal." Reagan's energized campaign roared back to life, continuing divisiveness that in the fall cost Ford more than Carter's thin margin of victory. The fierce fight over ratification of the canal treaties showed the place Panama occupies in America's psyche. Nicaragua has never had such a hold on America's attention. That is a shame. When, at last, Noriega goes, as he will, the United States will contribute a substantial sum-say $500 million-to heal wounds inflicted by U.S. policy on Panama's economy. If such a sum had been given to the contras, the hemisphere would by now have been cleansed of Nicaragua's Stalinist regime. Compared with it, Noriega's thugocracy is a gnat. As we huff and puff and try to blow Noriega's house down with "world opinion" and the dithering of Latin American leaders, it is clear that some slogans do not sound as good as they once did. For two decades, many Americans, including some early advocates of the Vietnam intervention, have been relentlessly didactic, extracting cautionary lessons from Vietnam. For example: It is wicked for the United States to throw its weight around as "policeman of the world." It is wrong to "interfere in the "internal affairs" of other nations (other than, say, South Africa). From the late 19th century until Vietnam, American isolationism expressed the conviction that America was too good for the world. Post- Vietnam isolationism holds that the world is too good for America. Such isolationism comes cloaked in the language of "multilateralism" --America can act but only in concert with coalitions of nations that almost never can agree to act. Suddenly, because of Panama, some people not recently heard praising American assertiveness seem to wish the United States had a bit more weight to throw around. Back in the bad old days, such ~s 1965, U.S. military force helped restore order and plant democracy in the Dominican Republic. America is too virtuous to do that sort of thing anymore. But some people who have deplored America's "imperial overreach" regret today's postimperial inability to reach Noriega. Do something: Still, thundering at Noriega is wonderfully cathartic. It is hairychestedness on the cheap for liberals looking for a place to look tough. And it dovetails nicely with antidrug demagoguery. Noriega's connection with the drug cartel makes him a useful target for politicians eager to tell Americans what many of them want to believe- that we can export blame for our drug problem. It is, of course, absurd to blame the problem on those who supply America's $150 billion demand for drugs. And it is absurd to believe that if Noriega were knocked out of drug trafficking, no one would step in to take his place. On all sides voices urge the United States to act but not in any way that might arouse latent Latin American resentments. Do something, but do not make anyone angry. Such advice is nicely balanced and utterly immobilizing. President Bush obviously places a high value on popularity. His craving for it is apparent in his peripatetic courtship of press and politicians, and in his almost abject pleas for "bipartisanship. In practice bipartisanship buys popularity by adopting Democratic policies as in the liquidation of the contras, and in giving Democrats shelter under the umbrella of a convenient fraud like the latest budget accord. However, a great nation cannot have its foreign policy controlled by a craving for popularity. It is far less important that the United States be loved by the Latin American masses than that the United States be feared by certain Latin American elites. Those elites, from whom the masses have much to fear, include antidemocratlc military officers contemplating coups and Sandinistas rigging sham elections. For the United States the wages of weakness are the contempt of the Noriegas of this world. For Latin Americans, the wages of U.S. weakness are much worse. George Will. "The Winds of Words." Newsweek 22 May 1989: 96.