Adele Keke, East Harerghe

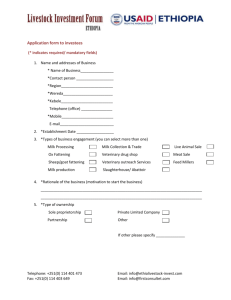

advertisement