The Shackle Collection at St Edmund`s College, Cambridge

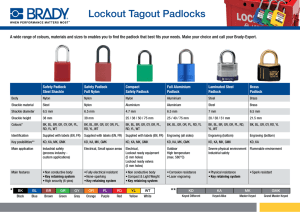

advertisement

“The Shackle Collection at St Edmund’s College, Cambridge” Presented at the 25th annual History of Economic Thought Society of Australia (HETSA) Conference, Melbourne, 5-7 July, 2012. Abstract A collection of George Shackle’s books is held in the library of St Edmund’s College, Cambridge. Some are by him and some are about him. Some have his handwritten inserts and some have his annotations in the margin, and these may be resources for Shackle scholars. The paper also distinguishes between hard and soft exegesis, and reflects on how an intellectual biography can be and ought to be written. Indeed these ancillary themes dominate the paper. Dr Bruce Littleboy, School of Economics University of Queensland b.littleboy@uq.edu.au Key words: Shackle, hard exegesis, soft exegesis, reading beyond the text Draft July 1, 2012 Introduction In the Easter Term of 2011 I enjoyed the honour of holding a Shackle Studentship at St Edmund’s College, Cambridge. In passing, the Master remarked that there were some items chosen by Shackle to go into St Edmund’s own library. I made a few discoveries that may interest admirers of Shackle, some of which I shall reveal here. Annotated copies of some economics books owned by Shackle are held at the College Library.1 An indirect result of this visit is that Peter Earl and I have contracted with Palgrave Macmillan to write a volume on Shackle for their series on Great Economists. Shackle has made a recent comeback in terms of recognition and respect: consider Richard Bronk’s The Romantic Economist and N.N. Taleb’s The Black Swan.2 Much of the specifics will be confined to the presentation itself. One reason is that I have been too inept to enquire sooner about permissions to quote or reproduce extracts. And a cuckoo has appeared in the nest. There must be differences between how a ‘pure’ history of ideas, an intellectual biography and a personal biography are written. It is not clear that the ‘scholarly’ style of a fine journal is necessarily the way to write it. A book is neither a PhD nor a series of articles. And a biography is not an intellectual biography. Furthermore, to the extent that the project relies on archival material, I realise that there may be rules and conventions to be at very least acknowledged. But I have not seen these rules laid out in a way that suggests widespread acceptance. This paper reflects on the practice of exegesis and intellectual biography. So this is really two different papers joined clumsily. It is a Q ship with a title that belies its content. And I have cut and paste from several sets of notes, which makes it likely that I have plagiarised myself in fragments of what follows, and sometimes by accident. Shackle’s inserts and annotations Here are samples of noteworthy remarks made by Shackle. (Under-preparation means that I do not report all instances here, and there is some repetition of last year’s conference paper.) Loasby (1989, p. 5) asks Would Shackle … accept Popper’s sophisticated falsificationism as complementary to his own analysis? In The Years of High Theory, it is not clear that he would. Shackle wrote in the margin of his copy3: “7/8/90 GLSS says he thinks that he would.” Loasby then portrays Shackle’s attempt to construct a comprehensive schema is to build a kind of theory that embraces all assumptions of potential interest. It should be judged by what it accommodates rather than what it forbids. Now Shackle’s lifework has been driven by the desire for a body of economic theory true to the human condition, yet he has never been a strong advocate of the rigorous and systematic testing of theories against evidence. (p. 6) To which Shackle responds: 7/8/90 GLSS accepts statement. Evidence is not something given us from above but it is something subject to criticism and attack. It is not impregnable. Evidence is a sort of suggestion. And this makes one wonder about the extent to which Shackle thought that Popper’s criterion is useable in practice. Loasby continues (p. 6), citing The Years of High Theory: One possible reason for his coolness toward testing may be the influence of F.A. Hayek’s arguments against the assimilation of the social to the natural sciences. What restrains Shackle from a firm commitment to such methodological dualism is not a belief in the value of natural science methods for economists, but a suspicion that natural science may share more of the difficulties of the social sciences than some of its methodological propagandists may care to admit (1967, p. 288) Shackle wrote: “GLSS agrees.” His tepid support for Popper buttresses Loasby’s observation (p. 6) that it is not clear that recognition of the fallibility of knowledge must inevitably lead to the conclusion that …theories must be judged by their ability to soothe the imagination, not by their correspondence with the truth. It is odd that Shackle did not posit a middle position. Exploring the evidence in the light of rival theories may result in one that soothes the mind discernibly more (or leaves rather less unease) than the other one does. Then it becomes a question of how much weight an actor (a firm or a policy-maker) places on this framework of interpretation and how much confidence is warranted in the most suitable choice that could be made in the light of one’s limited understanding. Loasby later refers to the difficulties faced by formalists in attempting to cope with how to apply their theories when economic processes may endogenously change the preferences of market participants. Marshall appreciated the difficulty, and this “helps to explain his insistence on translating mathematical expression into English, which was, for many, disappointingly vague” (p. 122). Shackle added (p. 122): 15/6/89 Vagueness is essential to its proper Reflection of Reality. Shackle hoped that a new vague mathematics (fuzzy sets) may be the way to wed reality and the language of mathematics, but this way of thinking failed to capture the imagination of economists, even those who admired Shackle’s teachings. Reflected reality is vague and distorted in Plato’s cave of flickering shadows. But we are not merely ignorant (as in Book VII of the Republic); Shackle has realised that there is too much that is unknowable. And elsewhere Shackle4 alludes to Popper on the indeterminacy of some systems. Last, Robin Rowley and Omar Hamouda (1988, p. ___) supply a 1938 passage from Shackle, which summarised (and apparently affirmed) Keynes’s use of the principle of certainty equivalence. Not surprisingly, Shackle wrote in the margin of the copy he donated to St Edmund’s: “Repudiated by GLSS 12.11.88.”). Those authors appear to prefer a strong form of the continuity principle as an exegetical guide to interpreting an author’s works through time. Around this time, 1937-8, Shackle had his life-changing insight into radical uncertainty. Outgrowth: soft and hard exegesis It is useful to say there is a distinction between hard science and soft science, physics and anthropology perhaps. When science becomes imprecise, perhaps because the object of study becomes complex, we start to refer instead to the application of art. There have been bitter and dogmatic disputes about the history of economic ideas, who said what and when. Even hard text can be re-arranged or re-emphasised to convey different impressions. As with disputes among econometricians, we may hope that obtaining more evidence and studying it more intensively will yield a consensus. Significance testing is also problematic beyond the formal context of statistics. Is there a useful distinction also to be made between hard and soft in the context of exegesis or intellectual biography? Once we use archival material rather than ‘hard’, considered, published text, the issue arises as to about what absolute and relative weight to place on this material. Is there, either for the writer or the reader, any tacit or unconscious assumption (well short of presumption) that this evidence is merely supplementary, corroborative, indicative or contextual? A writer or a scientist often needs to draw conclusions ranging from the tentative to the confident based on partial or ambiguous evidence. Writers sometimes prefer to suggest, as artists may. But some things are softer still, things that may indeed be the prerogative of the author, including interpretation, insight and hunch. These may be widely accepted as good ways to generate hypotheses, but does an author’s impression of the stated and unstated beliefs of a thinker under study itself count as evidence upon which the polite reader should place some weight? The judgement calls of those familiar with at the least the evidence permitted to reach the archives are integral to worthwhile biography. There is a jury of only one in this case though, and doubtless biographers and translators have written on how truly they mediate. If textual analysis of a fixed body of formal text is perilous enough, what then of combining personal biography with intellectual biography? Skidelsky’s success in his portrait of Keynes resulted from his own wide and deep knowledge of context as well as from a wide and deep volume of material about Keynes. There is firm but flexible cartilage between Keynes’s intellect and his life experience both personal and professional. ‘Thin’ and ‘thick’ are reasonably established terms5, but I am not sure that the distinction captures what is meant here. Context certainly counts, historical, cultural, intellectual and social. Rigour with rich context, analysis that is hard and thick, is scarce. C.P. Snow spoke of the two cultures, the literary and artistic on the one hand and the scientific on the other. Shackle aspired to bridge them. Norman Fisher, in his review6 of Shackle’s Economics for Pleasure, remarked that typical economists are “distinguished by an equal ignorance of both scientific and literary culture”. One is tempted also to think in terms of ‘tough’ and ‘tender’, as in William James’s categorisation, but this appears to cut through a simple two-by-two matrix of hard-soft and thick-thin. But it is plausible that one’s personality correlates with one’s preferred academic style. Reading personality certainly helps a researcher see the goals of the subject and the meaning and significance of their writings. Forming a view may go beyond what people have said in interviews and in print. There may be reasonable extrapolation. Someone who believes this will likely go on to believe that. And there may be legitimate scope for bootstrapping to fill in gaps. These are ‘soft’, and how respectable would such procedures be in an intellectual biography? One must simply sketch the personality as well as one can and hope that the reader will accept the conclusions made and extensions drawn. How and whether substantial hard chunks fit together in a coherent whole is what an intellectual biography is presumably supposed to do. In the case of Keynes we can construct a system because he has written on so many subjects, but for Shackle there will need to be educated guesswork. The connections will be softer. Shackle’s attitudes toward existentialism, complexity theory, and behavioural economics may be reasonably inferred from what may be regarded as a strategic silence. The detachment was deliberate, and there may have been a hint of disdain. And there is indirect corroboration from what is said and not said in personal correspondence. But how much weight can be put on what is not said? In such cases the absence of evidence is evidence of absence. If we look for evidence where one would expect it to be and in a few other places for good measure, and it still cannot be found, there are reasonable, though non-demonstrative, grounds for the belief that it simply is not there. Soft exegesis therefore includes reading beyond the text. Reading beyond the text Suppose we take an old-fashioned approach that an author’s text contains some core meaning that the intended reader can reliably discern. Clearly authors write for multiple audiences and they drop trinkets for some that others will either not see or not bother to stoop and gather. Just as a supermarket offers a cheaper, serviceable but inferior product to a certain clientele, the deluxe version is available to those willing and able to pay. And a writer may by design or accident leave different interpretations open. Even when writing for a professional audience, austere precision can be a barrier to easy communication and to rapid persuasion beyond a narrow cadre. Authors often let readers glide and sway a little so long as a current is taking them in the right direction. And rhetorical devices are switched on and off during the story. A writer may over-state for effect at one juncture and under-state elsewhere so the reader won’t recoil (quite yet). There may be footnotes intended as rewards (often punishments, in practice) for careful readers. There are assumptions about what the reader knows; some of these may be reasonably taken as understood by contemporaries, but later readers, or ones differently trained, may lack the background. There can be subtle disclosures (intended and unintended), ironies, playful winks, in-jokes and pointers elsewhere. There may be clues about why something was written that are not explicit in what was written. Such layers of meaning, shadings of nuance and sprinklings of apparent asides are also found in daily conversation. They are part of human language and its use. Writers know this, and readers should. And some readers are more empathic than others. Writers certainly know this. There are contexts when openness of meaning is not what the author wants. Henry Boettinger wrote the remarkable Moving Mountains in which he looks mostly at cases where corporate planners need to persuade and inform. Persuasion requires one set of techniques; instruction requires another. If a new system or strategy needs to be understood and implemented uniformly, the message needs to be passed along without error. When clarity is essential, content, style and tone are altered. A fine academic writer may write a textbook poorly. A text may be read in the social and intellectual context of the time it was written or instead sifted for what the reader regards as the nuggets. In an academic realm and elsewhere, writers have central ideas they are eager to convey and they are frustrated when misunderstood. But there are other ideas that a writer may be pleased to have conveyed that are not essential ones. And others are a hopeful spray of tiny seeds that may or may not find their soil. They may be hints of ways to advance an idea or to apply it. “But I have doubts.” “One could go further.” “I’m sure I’m right.” “Aren’t I clever?” “This is really so simple.” “Aren’t my opponents foolish?” “I am becoming frustrated by being so misunderstood.” These statements are not always explicit; sometimes the impression simply emerges in a reader’s mind. But in the case of academic exegesis, editors and referees rather prefer some textual or biographical support for these earnest intuitions. Claiming superior empathy does not suffice (except, perhaps, in a Cambridge seminar). Evidence may be scattered or be a matter of telltale changes in tone, and it may not look like very much when assembled. To go further and argue that the absence of something is of significance is a courageous rhetorical tactic. But if authors expressly or tacitly disassociate themselves from one doctrine and occasionally favour ideas and terminology employed by another doctrine, then, in the absence of other evidence (after diligent search), we are entitled make some cautious inferences about the pattern of their beliefs. If Marshall tells us that he was influenced by Kant, we may be able to use this to inform a textual analysis of the role of theorising in science. But this does not mean that Marshall would swallow the categorical imperative. Shackle admired harmony too highly not to seek it in his own ideas. The human condition, the subjective experience of making a choice, the diversity in scientific understanding and discourse, ethics and action, theory and application: these need to dovetail. This is what we know about Shackle. He was a softly spoken and gentle-natured Christian. He disliked confrontation and division and sought harmonising structures within which different modes of reasoning in economics could be reconciled. He argued that different ways of theorising were associated with different treatments of time. It’s not a case of right versus wrong or one of exposing underlying ideologies or interests. He was also a subjectivist in that each person is a unique perceiver and chooser. Free will rather than determinism governs the important steps that we genuinely choose in hope rather than in expectation. We lack the knowledge to make the best choice, and there is no predetermined future against which to judge our actions as best. Although a radical subjectivist, he was no moral relativist: ethics provided guidance to macroeconomic policy, for example. We may not know the future, but we know enough about what is broadly right or wrong. We imagine the consequences of our actions and future states of the world, but we do not control them. We may make our futures by making our choices, but nothing in Shackle suggests that we can validly construct our own values. But Shackle said little about policy or about the formal principles that should guide it. His position was unusual. He was a subjectivist and an individualist who favoured selective macro-interventions to promote human wellbeing. He may have learned some of his microeconomic subjectivism from Hayek, but he learned his macroeconomics from slices chosen from Keynes. Influenced by both of these towering minds, he was a convert of neither. He remained quietly obstinate in championing his own intellectual assemblage. As time passed, the gaps filled and the structure took form. Converts did not flock, but his principal ideas retain influence and regard. His ideas received high-level attention but proved unpersuasive to the mainstream, especially when it became clear how subversive his ideas were. Though acknowledged by scholars of epistemic uncertainty and respected by scholars of Keynes and historians of economic thought, his lack of influence on practical affairs and on the core teachings of economics must have disappointed him. (Need one document this disappointment?) For all of this, there is little direct hard evidence, but I am confident that this is a good personal and psychological reading. One could just present his quirks and leave the personality analysis to the reader. But the author may and should write to provoke the reader into such an engagement. The student of Shackle finds that his shyness and his reticence obscure the philosophical background that informs his work. Shackle states his case in his own way without citation or quotation beyond a particular point in focus. He almost made a point of not indicating that he had read contemporaries. Even books he reviewed or praised did not appear to influence expressly what he wrote. He dwelt on Keynes as he did on nobody else, though he was no mere expositor of Keynes. It is hard to write an intellectual biography of such a private person. Shackle shared Keynes’s rejection of Benthamism as the basis for understanding human conduct and for providing a basis for social policy. While Keynes stressed the importance of policies that are moderate and just, Shackle acknowledges this more discretely. Shackle was not himself a man of practical action, though he thought his ideas were ones that practical people could use. Decisions in life are made in an ocean of uncertainty.7 Intuition, experience and imagination all count, and this is all we have. There is no machine of prediction. I conjecture that uncertainty rendered Platonic certainties infeasible, and even Aristotle’s common sense struggles for sufficiency. Hope and imagination were the drivers. Conventions gave some stability behind your back, and some reasonable hope for overall stability looking forward, but your fate in your own small world depends a great deal on your efforts and creativity as well as the tumbling reconfiguration of the world that you may encounter. Outcomes were outside human control. Too much was opaque to human understanding. Prudence suggests the need to consider scenarios, to rehearse plausible responses and to retain uncommitted reserves for contingencies. Our human condition precludes the quest for optimisation, and we do not act as if we calculated and compared the net expected benefits stemming from all possible actions. In Shackle, there is plenty of room for conventions concerning prices and rules of market conduct, but reality is never described as recurring conjunctions of events. “Lively imaginings” in Shackle pertain to the future, not to our apprehension of the present. Claims that Shackle was nihilistic, broadly in the sense of Nietzsche, are easily dismissed8. Others see postmodernism and existentialism in his works, but Shackle didn’t. We may be confident about what he is not. This is soft exegesis, but firmer, more empirical, exegesis may miss what is too subtle to be measured and counted. The reasoning proceeds like this. If someone affirms A and repudiates B, they probably agree with C, or something close to it. Though D is a possibility too, there is no hint of D while there are hints of C. This person probably is an A+C. People who are A+C often hold attitude E too. Our subject is temperamentally well suited to E, so, in the absence of other evidence, to conjecture A+C+E is plausible and some degree of confidence may be warranted. Does a high emotional IQ improve one’s (human) exegesis? Admittedly, the author is seldom well placed to judge this. Intuition, sympathy and empathy must count. An authentic reading at the psychological and temperamental levels may yield a better substantive reading of the text than following the practices of pedantic formalism and literalism. By the way, a formalist is simply anyone who uses words more carefully than I do9. Here is the bald argument in application. Shackle affirms free will and individual choice. He rejects applying the machine metaphor to individual people or to social systems. He is a Christian and has externally anchored normative tenets. Man is not the measure of all things. Intuition and experience guide an individual’s practical economic decisions. Governance should be wise and ethical rather than a matter of social engineering. As I have argued elsewhere, this constellation suggests that Shackle may be oriented to a form of Platonism, which is easily associated with Christianity. Truths are in harmony. Mathematics ultimately embraces economics, but it will be of a fuzzy kind, and humans will not succeed in mastering uncertainty. Words permit much, but Shackle’s quest to systematise and formalise human choice under uncertainty failed, if success is understood as widespread acceptance. The crystalline equations are for God’s eyes, not ours. Formality can take us only so far; Shackle at one stage tried to tame human choice and to formalise surprise and how we try to avoid it. He failed to produce something of seductive and wondrous coherence; he did not meet his own criteria. He could not find the coping stone. We are left only with his evocative prose and a sense that he was tantalisingly close. Soft collisions Exegetes twitch when they encounter contradictory passages that ruin the neatness of their narrative. They often regard the anomaly as being too deep or difficult for the author to have seen or resolved. The situation may have been framed wrongly though. The reader may have the problem rather than the author. An individual author can hold views simultaneously that appear irreconcilable. It is the reader’s responsibility carefully to consider how to respond. An issue that frequently puzzles exegetes is how commonly those under study take positions that seem to undermine the coherence of the own writings. No reader expects a writer to be absolutely consistent and unchanged over time. We are familiar that writers learn from social circumstances, personal experience and exposure to new ideas. We also know how tricky it can be to gauge whether a lengthy discussion of a particular topic, which lies uncomfortably with the rest of their writings, represents careful consideration of an exception to an unchanged broad rule or whether it should be as a shift in the balance of belief. What was once considered minor is now central, but perhaps only to the current discussion. We know that weight given to an idea is not the same as number of words devoted. If something is unmentioned, the writer may regard it as self-evidently true or self-evidently false. Intellects of quality are sometimes given special permission to appear to embrace impossible combinations. How could Schumpeter be so dismissive of the content and ambitions of neoclassical economics and yet be so admiring of the Walrasian program?10 Erik Reinert in a seminar at Clare Hall in Cambridge (May 2011) said that he regarded Schumpeter as intellectually schizophrenic on this matter. Another possibility though is that exegetes are prone superficially to read inconsistencies into a text or into a life. Some people are puzzled by a sobbing Nietzsche rushing to a defence of a beaten horse. They say that he rejected his own writings at the end, or that syphilis had clearly run its course. However, there may be no problem to solve. The will to power and the contempt for the ordinary never extended to horses. Nietzsche’s feelings towards quadrupeds are his own; it was the vulgar and conventional exercise of human power that affronted him. I have no evidence whatever to support this view, but I still think I may be right or roughly so. How can Keynes sometimes write as though the economy is a machine with a structure that can be rendered mathematically and in the next chapter (12) show that economic uncertainty and human psychology prevent this? Shackle pondered what he regarded as an unresolved tension, a kind of flaw, in Keynes. He did not view it as a creative or dialectic tension, one that he should engage with as contemplating a Zen koan. Perhaps he ought to. And what can we make of Hayek’s emphasis on equilibrium in his macroeconomics and of evolution and indeterminacy in the micro-realm? Shackle was frustrated by it. Your own intellectual stock is a network; even if serviceable in your own judgement, it need not be harmonious to outsiders. Some links bear a heavy load of traffic; others are nonetheless important. We can describe our own ideas as organic in some sense but that does require a consistency honed by the tests of argumentation and introspection. Evolution in the biological realm speaks of redundancies, imperfections, spandrels, yet exegetes write as though they expect either formal rigour or an aesthetic or poetic coherence. It is said that biological evolution has zero IQ; the process is the best-surviving feasible response at the time. The process is not forward looking, and what solved a problem at one step locks us into a pathway which an intelligent and informed designer may not have selected. Even if we accept that people have intelligence and strive to look ahead, intellectual change in neither individuals nor groups is what economists call efficient. One sometimes encounters claims that one could not change a single note of a certain symphony without spoiling it, but this likely is the foolishness of the dilettante or the unreflective expert. Whether seeking or demanding logical or artistic “consistency”, we succumb to a Puritan snobbery. Yet there may be more consistency than we think in what we think. Many a student leftist flips over to the conservative establishment, which is seemingly a major shift, but it may result simply from the simple realisation that socialism didn’t work as well as advertised. Change just one assumption, and the conclusion may be reversed in an instant. The logical structure of one’s core beliefs may remain largely intact, and no sense of dramatic change felt. Those who tell you that you have changed don’t really understand. Soft, entirely soft, is it not? But still it is right, at least to some uncertain extent. Soft rules Softness also surrounds the rules and conventions of intellectual biography. And are these rules, if they exist, in any way different from the ordinary sense of probity in one’s disclosures? Disclosures in the case of Shackle will not be at all shocking, I must point out. There was no great and gory academic backstabbing in Shackle’s immediate circle. There are no kiss-and-tell confessions. But some living people could be very slightly embarrassed. I close with some questions that I cannot well answer. Questions like these keep bobbing up. Are annotations in books left for posterity (even) more valid than personal letters left for posterity? My answer is, ceteris paribus, yes. If you write a letter to someone, it may predictably end up in an archive, but what about the “personal” inscription in a book? My answer is that this is generally appropriate to disclose. But what about revealing that gifts of books were never read? This is a matter of etiquette rather than ethics, but again is there a consensus that authors can be confident in relying upon? There may be ‘rules’ or a set of good manners about the treatment of archival materials11. Suppose Shackle writes something negative or embarrassing about someone (a rarity, which is itself noteworthy) in a letter, or in the margin of a book. Suppose somebody makes a personal revelation to Shackle in the middle of a letter of a more professional kind. Are there rules or guidance from other historians of ideas and from exegetes? What training in protocol do we provide? It is said that training teaches the rules and experience teaches the exceptions. This may merely move the problem, but perhaps to the right place. Enough. Appendix (Located with the collection at St. Edmund’s College, Cambridge) The George Shackle Bequest Shelf Mark 330.1 SHA Chosen by Bruce Littleboy (Shackle Scholar 2011) George Shackle was connected to Cambridge in spirit and life. Most of his books were published through the University Press, and his collected papers are housed in the University Library. His connection with St Edmund’s was through Professor Stephen Frowen who was a Fellow Commoner here and who died in 2007. Frowen was Shackle’s postgraduate student at Leeds. The two became close friends, and their correspondence literally fills a book, Economists in Discussion: the correspondence between G.L.S. Shackle and Stephen F. Frowen, 1951-1992, published in 2004. Professor Frowen established in perpetuity The GLS Shackle Biennial Memorial Lecture series. Under the will of his widow, Catherine, a bequest was made to the College to fund a Shackle Fellowship and Studentship to promote an interest in and development of Shackle’s ideas. Catherine donated an important part of George’s book collection to the College. The collection of about forty works itself stands as a resource to attract scholarly study. Many are by Shackle, while others are about him and the central themes of his life’s work. Some are annotated in the margin by Shackle and indicate his careful reading; a few others contain handwritten inserts. Through bequests the College now not only provides economic support to Shackle scholars but now also provides material of significance deserving study in its own right. Shackle aspired to re-orient economic theory by centring it on the deep uncertainty that decision-makers must confront. There is no mechanism that reveals the future to us now because we make the future through our current choices. We only have our hopes and imaginings; we do not have a quantitative formula as our guide. Shackle was a quiet and gentle man, but his ideas remain intriguing and highly subversive. 1 Others are held in Liverpool, but time did not permit a visit there. Surely it’s not the black swans you really need to worry about; it’s the leopards. (Swans can get testy though.) 2 3 This is the copy that Loasby gave to Shackle, dedicated to him with the handwritten addition, “scholar and gentle man with admiration and affection”. It was donated to the library at St Edmund’s College, Cambridge. In a letter to Kirzner (11 May, 1980; 9/12) Shackle referred to the “cloudscape of experience”, a possible allusion to Karl Popper’s Of Clouds and Clocks (1966). 4 In 2003 on HES: DISC there was an exchange (Weintraub, Gunning, Colander, Lee…) regarding thin and thick histories, and D. McCloskey has written on thin and thick methodologies. 5 6 Education, “For Students Only”, March 11 1960. 8 Regular HETSA attendees may remember my earlier papers. 9 This is mere jest. Tony Lawson, for example, uses (almost) ordinary language with extraordinary precision. See Erik Reinert, ‘Steeped in Two Mind-Sets: Schumpeter in the Context of the Two Canons of Economics’, in Backhaus, Jürgen (ed.) Joseph Alois Schumpeter: Entrepreneurship, Style and Vision, Boston. Kluwer, 2003, pp. 261-292. 10 There have been HES: DISC exchanges on whether referee’s reports in archives are open for researchers to publish. 11