APS Values - Australian Public Service Commission

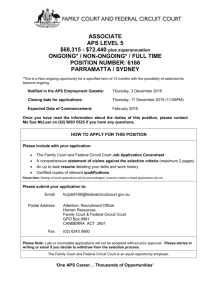

advertisement