Intraosseous Access Intraosseous (IO) access is an important

advertisement

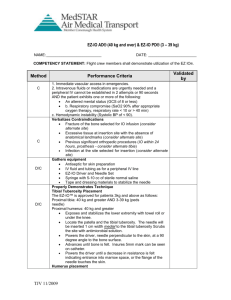

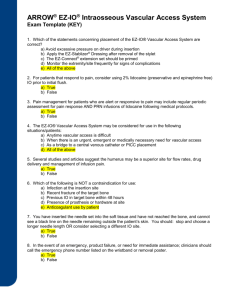

Intraosseous Access Intraosseous (IO) access is an important component of the vascular access armamentarium for all clinicians. Studies have shown that IO access can be easily established by individuals with little training and is faster than intravenous (IV) access. Due to unfamiliarity, the technique is underutilized. IO access is one of the quickest ways to establish vascular access for the rapid infusion of fluids, drugs, and blood products in an emergency. In adults and pediatrics after 2 peripheral IV attempts, IO is the next-line modality. IO vascular access was first used in 1922 as a method to administer fluids and medications through the venous system of the bone marrow cavity into systemic circulation. The bone marrow cavity contains a rich vascular network within the Haversian canals. In the 1940s, IO access gained popularity for pediatric infusions. Through the 1960s and '70s, flexible catheters replaced IO in popularity. In the 1980s with the development of such programs as PALS (Pediatric Advanced Life Support) and ATLS (Advanced Trauma Life Support), IO access resurfaced once again as a viable option. Although early guidelines recommended limiting IO access only to children aged 6 years or younger, recent studies have shown that IO access is safe in patients of all ages. IO access in newborns is faster than umbilical vein catheterization. IO access can be established within 1 minute. IO access is a temporary emergency measure and should be limited to 7 hours until intravenous or intra-arterial access is achieved. IO access is indicated when immediate vascular access is required, but standard peripheral IV access is challenging or impossible. Typical circumstances include cardiac arrest, rapid sequence induction, profound hypovolemia and decompensated shock, severe burns, trauma resuscitation, mass casualty situations, and overwhelming sepsis. IO access is contraindicated in an injured lower extremity, at the site of local infections, amputations, or fractures, or recent IO placement in the same extremity and may require an alternative IO site. Some orthopaedic procedures such as a total knee replacement would leave the IO space inaccessible secondary to the indwelling prosthetic device. Fractures may cause fluid or medications to escape from the intramedullary space. The site of choice for IO insertion in adults and pediatric patients is the proximal tibia 1-3 cm below the tibial tuberosity, then medial along the flat anterior surface (arrow). In adults, the site is easily identified as the wide flat anteromedial aspect of the bone lying just under the skin. Other anatomic sites for IO insertion include the proximal tibia, distal femur, medial malleolus, proximal humerus, sternum, and iliac crest. IO devices have evolved significantly over the years. The first-generation IO devices (left) had to be manually forced into the bone to gain access to the medullary canal. Second-generation devices, like the Bone Injection Gun (B.I.G.), are designed to facilitate rapid IO access in less than 60 seconds. The B.I.G. (right) has a spring-loaded handle that injects the IO needle to a preset depth depending on the patient's age. The third-generation IO devices are autoinjectors, like the EZ-IO® by Vidacare (Shavano Park, Texas) (left). It is one of the most commonly used devices in the United States. Both the length of the needle (right) and the depth of insertion can be customized. The beveled, hollow, drill-tipped needles are designed to provide safe and controlled access through the bone. The device contains a lithium battery that can be expected to last for 2000 IO insertions. Gaining IO access via the EZ-IO® proceeds in a stepwise fashion. 1. Choose the site: The tibial tuberosity is the principal landmark; however, in pediatric patients the tibial tuberosity can be difficult or impossible to palpate. If you cannot palpate the tibial tuberosity, the insertion site is 2 finger widths below the patella and then medially along the flat surface. 2. Prep the site with a topical antiseptic, such as povidone iodine. 3. Administer local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine in the awake patient. 4. Select the appropriate needle for the patient's age. The adult set is blue, 25 mm in length for patients 40 kg and greater. The pediatric set is pink, 15 mm in length for patients 3-39 kg. If your patient fits on the Broselow tape, use the pediatric needle set. 5. Attach the needle to the EZ-IO® drill. 6. Position the needle and EZ-IO® drill at 90 degrees to the bone. Press the trigger on the drill handle and apply moderate pressure, while letting the drill do the work for you. When you feel the "pop" -you're in. The pain of IO insertion is generally equivalent to that of peripheral IV insertion. 7. Disconnect the EZ-IO® drill while leaving the needle in place. 8. Withdraw the needle stylet and confirm placement by aspiration of blood with syringe; however, the inability to aspirate blood does not necessarily indicate improper placement. There may be a blood clot in the needle if there is a delay between placement and aspiration. 9. Attach the catheter to the needle hub. Tape or other adhesive may be helpful to ensure that access is not lost during manipulation of the needle. 10. Flush with sterile solution: 10 mL in an adult and 5 mL for pediatric patients. In adults, the use of a pressure infuser will improve flow rates. Pediatric infusion, however, should be carefully regulated via a syringe. The pain from IO infusion may be severe, but many studies have validated the use of 5 mL of 2% lidocaine infusion after IO access to provide analgesia. Blood can be aspirated with a syringe and sent for laboratory testing. Any medications that can be given through a peripheral or central line can be given through the IO route, and the dosing does not change. The sternum was the original site of access reported, and it is still a useful option in adult patients. The problems with sternal access are that it can interfere with chest compressions during resuscitative efforts, and it does carry a risk for pneumothorax, mediastinal injury, great vessel injury, and death. Complications from IO placement must be carefully monitored. IO access is meant to be a bridge to alternative access. Cellulitis and osteomyelitis may develop, especially if there is poor antiseptic technique or prolonged needle placement (> 72 hours). Extravasation due to incorrect insertion may lead to compartment syndrome or incomplete infusion. A bent needle (shown) may develop if proper landmarks are not utilized. Bone fracture or through-and-through penetration may occur from excessive force, but this is less common with newer devices that do not rely on brute force for access.