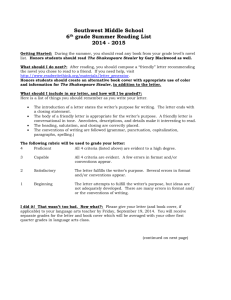

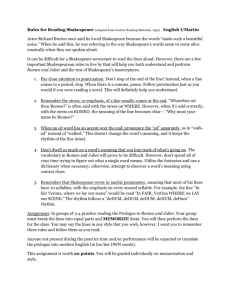

AP Handbook - SchoolRack

advertisement

Jeri Birdwell English II Pre-AP jeri.birdwell@pflugervilleisd.net AP HANDBOOK Students: This handbook is to be in your possession each time you enter my classroom. Enclosed are vital handouts that will help you succeed in my class and in college. You should will them to your children, and they, in turn, to theirs. Keep this handbook in a three-ring binder. I will not replace lost handbooks. It is your responsibility to do so. 1 2 AP HANDBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Literary Terms Glossary 5 2. Levels of Questions 24 3. Tone Words 25 4. Fiction Analysis a. Character 27 b. Setting 28 c. Plot 30 d. Theme 32 5. Mnemonic Devices For Literary Analysis a. TPCASTT 34 b. SOAPS 35 c. DIDLS 35 6. Expanding DIDLS: Analyzing Prose and Poetry 7. Plagiarism: A Very Big Deal/Pitts Article 36 37 8. POWER 41 9. Quadcards 42 10. Phrase Toolbox 43 11. The Essence of Style/Literary Analysis 45 12. Mrs. Lake’s Handy Dandy Grammar Guide 3 46 4 LITERARY TERMS AKA DEVICES THAT WILL HELP ME BECOME A MORE DISCERNING READER, SMARTER THAN THE AVERAGE JOSEPHINE, FITTER IN THE ACADEMIC ARENA. THUS BETTER EQUIPPED THAN MY LESSER (NON-PANTHER) NEIGHBORS WHILE TAKING THE AP TEST, I WILL ENTER COLLEGE WITH SUPERIOR DENDRITIC ACTION. MY FAMILY WILL BEAM WITH PRIDE, AND I WILL HOLD MY HEAD UP JUST-THAT-MUCH-HIGHER. TERM DEFINITION EXAMPLE(S) and/or ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Absolute A term applied to anything totally A word, such as “unique,” that cannot be compared (in vocabulary) independent of conditions, limitations, controls, or modifiers Absolute A phrase consisting of a noun or pronoun (in grammar) and a participle as well as any related modifiers. Absolute phrases do not directly connect to or modify any specific word in the rest of the sentence; instead, they modify the entire sentence, adding information. They are always treated as parenthetical elements, set off by commas or dashes. Abstract Abstract language refers to things that are (opposite: concrete) through the senses but by the mind Acronym A word formed by combining the initial intangible, that is, which are perceived not letters or syllables of a series of words to form a name or modified “About the bones, ants were ebbing away, their pincers full of meat.” Lessing, African Stories “Six boys came over the hill half an hour early that afternoon, running hard, their heads down, their forearms working, their breath whistling.” Steinbeck, The Red Pony Truth, God, education, vice, transportation, poetry, war, love NATO - North Atlantic Treaty Organization radar - radio detecting and arranging SAT – Scholastic Achievement Test CD-ROM - Compact Disc read-only memory Act A major division of a drama Dating from ancient Greece, the five-act structure corresponded to the five main divisions of dramatic action: exposition, complication, climax, falling, and catastrophe. Subsequent centuries have seen the evolution of the three-act and one-act plays. Action The series of events that constitute a plot, what the characters say, do, think, or in some cases fail to do Affix Allegory A verbal element added before (prefix), inside Prefixes: Millimeter, euphoria, predetermine meaning Suffixes: wonderful, resistance (infix), or after (suffix) a base to change its A narrative (e.g., fable, parable, poem, story) that serves as an extended metaphor. The main purpose of an allegory is to tell a story that has characters, a setting, and other types of symbols that have both literal and figurative meanings. 5 Infixes: abso-freakin-lutely, edumacation William Golding’s Lord of the Flies George Orwell’s Animal Farm Alliteration The repetition of identical initial consonant sounds or any vowel sounds in successive or closely associated syllables, especially stressed “The moan of doves in immemorial elms, And the murmuring of innumerable bees.” Tennyson, “Come Down, O Maid” syllables Allusion A figure of speech that makes brief reference to a historical or literary figure, event, or character who underwent years of anguish yet object. Its effectiveness relies on a body of knowledge shared by writer and reader. The patience of Job refers to the biblical never relinquished his faith. “But just as soon as the sun (which should make you happy)/Moves well above the horizon, as the Goddess of Morning Aurora/ Draws back the shady bed curtains from her bed,/My depressed son runs away from the light and comes home,/And locks himself in his bedroom” Ambiguity (am-bi-GYOO-i-tee) Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet The capacity of language to function on more In Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s main meaning, with resultant uncertainty as to the translucently pure as a cliff of crystal." A surface clause the epitome of integrity, but Conrad leaves it to the than one level, to have more than one intended significance of the word, phrase, or character, Marlow, speaks of Kurtz as a “soul as reading may show Kurtz to be morally upstanding, discerning reader to derive the connotations of pure and crystal, given his knowledge of Kurtz. Even Marlow seems to be ambivalent in his own feelings towards Kurtz. Ambivalence The existence of mutually conflicting feelings In Keats’ line, “O golden-tongued Romance,” or attitudes, often used to describe the “golden-tongued” could mean euphonious or contradictory attitudes an author takes toward characters or societies Anachronism (uh-NAK-ruh-niz-uhm) Assignment of something to a time when it was not in existence deceptive. Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court Mechanical clocks in Julius Caesar Renaissance artists often depicted ancient subjects in contemporary clothing Anadiplosis (an-uh-di-PLOE-sis) A kind of repetition in which a word or "All service ranks the same with God, place in one sentence or line is repeated at the Are we." phrase coming last or in another important beginning of the next With God, whose puppets, best and worst, Anagram A word or phrase made by transposing the Analogy A comparison between two things, alike in An English teacher is like a golden retriever. S/he is certain aspects, usually by which something usually good with kids, has a reputation for being something more familiar. A simile is an load of you-know-what. letters of another cask Robert Browning, Pippa Passes dormitory sack snooze alarm unfamiliar is explained by being compared to expressed analogy, a metaphor an implied one. 6 dirty room Alas! No more Z’s fiercely loyal, and is quite practiced at sniffing out a Anaphora Repetition, in which the same expression (uh-NAF-er-uh) (word or words) is repeated at the beginning (opposite: epistrophe) sentences. Anecdote A short narrative detailing particulars of an of two or more lines, phrases, clauses, or I have been one acquainted with the night. I have walked out in rain—and back in rain. I have outwalked the farthest city light. Frost, “Acquainted With the Night” interesting episode or event Annotation The addition of explanatory notes to a text by the author or an editor to explain, translate, cite sources, comment, or paraphrase Antagonist The adversary of the protagonist of a drama, Jack in Lord of the Flies Anthem A song of praise, rejoicing, or reverence National and religious anthems Antihero A protagonist of a modern play or novel who Holden Caufield from Catcher in the Rye attributes of the hero. This hero is graceless, Edmond Dantes from The Count of Monte Cristo novel, short story, or narrative poem has the converse of most of the traditional inept, sometimes stupid, sometimes dishonest. Bob Ewell in To Kill a Mockingbird Heathcliff from Wuthering Heights Batman Sweeney Todd Mal Reynolds from Firefly (TV sci-fi) Antithesis (an-TITH-uh-sis) A figure of speech characterized by strongly “Man proposes, God disposes.” ideas. True antithesis is presented in similar And wretches hang that jury-men may dine.” contrasting words, clauses, sentences, or grammatical structure. “The hungry judges soon the sentence sign, “Extremism in defense of liberty is no vice, moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” ~Barry Goldwater Brutus: “Not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved Rome more.” Shakespeare, Julius Caesar Aphorism (AF-uh-riz-uhm) Apostrophe A brief saying embodying a moral; a concise Pope: Some praise at morning what they blame at words Emerson: Imitation is suicide. A figure of speech in which someone (usually, “Age, thou art sham’d!” statement of a principle given in pointed night. Franklin: Lost Time is never Found again. but not always absent), some abstract quality, or a nonexistent personage is directly Shakespeare, Julius Caesar addressed as though present. Archetype A character, action, or situation that is a prototype, or pattern, of human life, Characters: the temptress, mentor, damsel in distress, the “old crone,” the naïve young man occurring over and over again in literature from the country Actions and situations: a quest, an initiation, or an attempt to overcome evil Argumentation One of the four chief forms of discourse, the others being exposition, narration, and description. Its purpose is to convince by establishing the truth or falsity of a proposition. Aside A dramatic convention by which an actor directly addresses the audience but is not 7 The main character in Malcolm in the Middle does this all the time. supposed to be heard by the other actors on stage. Assonance The repetition of vowel sounds but not consonant sounds Asyndeton A lack of conjunctions between succeeding (uh-SIN-di-ton) phrases, clauses, or words. explanation) “Veni, vivi, vici”(I came, I saw, I conquered). night" Caesar “…government of the people, by the people, for the people…” (opposite: polysyndeton) (See mood for a fuller rage, against the dying of the light." Dylan Thomas, "Do not go gentle into that good (opposite: consonance) Atmosphere "Old age should burn and rave at close of day;/Rage, Lincoln The prevailing mood of a literary work, usually when established in part by setting or landscape Axiom An aphorism whose truth is held to be self- "Goods and services can be paid for only with goods evident. In logic, an axiom is a premise and services." accepted as true without the need of demonstration and is used in building an argument. Background Either the setting of a piece of writing or the tradition and point of view from which an author presents his or her ideas Banality A quality referring to phrases and statements “Things are not always as they seem.” that lose effectiveness due to having been Wording that tempts you to use quotation marks over-used. Such wording is characterized as stale, trite, clichéd. because you’ve “heard it before, [you’re] just not sure where.” Anything that starts with, “A wise man once said….” Bard Today, a poet; historically, a poet who sang of heroes THE Bard Belles-Lettres William Shakespeare. Period. Paragraph. (Fr. , bel-LE-tR ) uh That body of writing (drama, fiction, poetry, and essays) valued for its aesthetic qualities and originality of style and tone rather than Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland Jane Austen’s Emma its informative or moral content Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations Bildungsroman A novel that deals with the development of a (BIL-doongz-roh- young person, usually from adolescence to Bit A very small role in a dramatic piece Sampson and Gregory in Romeo and Juliet Blank verse Poetry with unrhymed lines but with regular What flocks of critics over here to-day, mahn) maturity meter, usually written in iambic pentameter Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (Jem, not Scout) As vultures wait on armies for their prey, All gaping for the carcase of a play! With croaking notes they bode some dire event, And follow dying poets by the scent. Dryden, “All for Love” 8 Bon Mot A witty or clever saying “A man cannot be too careful in the choice of his (BON MOE) enemies” ~Oscar Wilde Caesura A pause or break in a line of verse To err is human, to forgive, divine. A harsh, unpleasant combination of sounds “Whereat, with blade, with bloody blameful blade, (si-ZHOOR-uh) Cacophony (kuh-KOF-uh-nee) He bravely broach'd is boiling bloody breast” (opposite: euphony) Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream Caricature Writing that exaggerates certain individual qualities of a person to produce a ridiculous effect Character People or animals who take place in the Scout, Jem, Atticus, Tom Robinson, and Boo Radley One for whom the author emphasizes a single Mrs. Dubose in To Kill a Mockingbird action of a literary work Flat important trait Round Jem in To Kill a Mockingbird One with a complex, fully-rounded personality Dynamic Static in To Kill a Mockingbird One who changes in response to the Jem in To Kill a Mockingbird One who changes little over the course of a Dill in To Kill a Mockingbird experience through which s/he passes narrative Foil A character, usually minor, designed to Frances, the cousin who brutalizes Scout, would be Stock A flat character in a standard role with Aunt Stephanie, the town’s spinster and gossip, in Characterization highlight qualities of a major character standard traits To Kill a Mockingbird The author directly states a character’s traits “Miss Caroline was no more than twenty-one. She (Direct) Characterization (Indirect) considered a foil to Jem in To Kill a Mockingbird had bright auburn hair, pink cheeks, and wore crimson fingernail polish.” A method of characterization in which “You’re scared,” Dill said… they say (dialogue), do (actions), what others Dill said, “You’re too scared even to put your big toe readers learn about characters through what say about them, and how other characters “Ain’t scared, just respectful,” Jem said. The next day in the front yard.” react to them Chronology The temporal design of a work. A story told from beginning to end has a linear chronology. Cinquain (sing-KANE) Any five-line stanza Cliché Any expression so often used that its “Every cloud has a silver lining.” freshness and clarity have worn off “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink.” Coined words Words consciously manufactured Telephone, airplane, zipper, blurb, spoof 9 Colloquialism An expression used in informal conversation (kuh-LO-kwee-uh- but not acceptable universally in formal liz-uhm) speech or writing I’m worn to a frazzle. She told him how the cow ate the cabbage. Little man, I’m fixin’ to tear you up if you don’t git in this house right this instant! Comedy As opposed to tragedy, a lighter form of drama that aims to amuse. In medieval times, comedy referred to non-dramatic works with a happy ending and a less exalted style than tragedy. Comic relief A humorous scene, incident, or speech, Mercutio’s death scene in Romeo and Juliet contrast, heighten the seriousness or The drunken porter in Macbeth interjected in the course of a drama to, by highlight the tragedy of the story Concrete The gravedigger scene in Hamlet Having the quality of the physical, tangible, actual, real, particular (opposite: abstract) Connotation The emotional implications and associations that words may carry, be they personal or private, group-oriented (national, linguistic, (opposite: denotation) Consonance racial), or general or universal (held by all or most people) the repetition, at close intervals, of the final consonants of accented syllables Context The cat peered into the night having stopped just short of the hut. Matter that surrounds a word or text in question Couplet Two consecutive lines of verse with end rhymes Three couplets follow: “Love looks not with the eyes but the mind; And therefore is winged Cupid painted blind. Nor hath love’s mind of any judgment taste; Wings and eyes figure unheedy haste; And therefore is Love said to be a child, Because in choice he is so oft beguiled.” Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream Deduction The process of deductive reasoning that moves from general principles to individual cases Denotation The dictionary definition of a word Details The facts, revealed by the author or speaker, (opposite: connotation) that support the attitude or tone in a piece of poetry or prose Deus ex Machina The employment of some unexpected and kuh-nuh) right Dialect The speech of a particular region or group as “Now don’t you fret, ma’am,” [Little Chuck Little] it differs from that of standard speech said. There ain’t no need to fear a cootie. I’ll just (DAY-uhs eks MAH- improbable incident to make things turn out 10 (Latin for “god from the machine”) fetch you some cool water.” Dialogue Conversation of two or more people Diction Word choice intended to convey a certain (See denotation and effect town when I first knew it. In rainy weather the streets turned to red slop…the courthouse sagged connotation) Double Entendre (DUHB-uhl-ahnTAHN-druh) “Maycomb was an old town, but it was a tired old on the square.” A word or phrase that has dual meanings, one of which is often sexual in nature "If I told you you had a beautiful body, would you hold it against me?" ~Benny Hill, Groucho Marx, John Cleese, and many others “I will be cruel with the maids and cut off their heads.” Sampson, Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet Drama A play; a dramatic work intended for performance by actors on a stage Effect Totality of impression or emotional impact Elaboration A rhetorical method for developing a theme Romeo and Juliet, A Raisin in the Sun, Julius Caesar, The Crucible, Death of a Salesman or picture in such a way as to give the reader a completed impression Elizabethan Age The segment of the Renaissance during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603). Ellipses (dot, dot, dot) A construction in which words are left out or You only need three dots in the middle of a sentence; at the implied end of a sentence, a fourth dot would be the period. End Rhyme Rhyme at the ends of lines in a poem “The old dog barks backward without getting up. I can remember when he was a pup.” Frost English Sonnet A sonnet consisting of three quatrains (Shakespearean followed by a couplet, rhyming abab cdcd Epanalepsis The repetition at the end of a clause of a word sonnet) (ep-uh-nuh-LEP-sis) efef gg or a phrase that occurred at its beginning Blood hath bought blood, and blows have answered blows;/Strength match’d with strength, and power confronted power. Epic A long, narrative poem about the adventures Epic Simile An elaborated comparison Epigram A pithy saying of a central hero Shakespeare, King John Homer’s Odyssey Virgil’s Aeneid To be safe on the Fourth, Don't buy a fifth on the third. ~ James H Muehlbauer God bless our good and gracious king, Whose promise none relies on, Who never said a foolish thing, Nor ever did a wise one. Epigraph An inscription on a tomb or on a statue or a coin 11 “In God We Trust” Wilmot, "Impromtu on Charles II" Epilogue A concluding statement Epiphany A sudden unfolding in which a character (i-PIF-uh-nee) proceeds from ignorance and innocence to knowledge and experience Epistle Any letter, but usually limited to formal (i-PIS-uhl) composition written to a distant individual or Epistrophe A rhetorical term applied to the repetition of (i-PIS-truh-fee) group the closing word or phrase at the end of “And all the night he did nothing but weep Philoclea, sigh Phgiloclea, and cry out several clauses ~The New Arcadia Philoclea.” (opposite: anaphora) “…of the people, by the people, for the people…” Essay A moderately brief prose discussion of a Ethos The source's credibility, the speaker's/author's Lincoln restricted topic authority. Ethos (Greek for 'character') refers words on mental illnesses than that same to the trustworthiness or credibility of the writer or speaker. Ethos is often conveyed through tone and style of the message and through the way the writer or speaker refers I would sooner trust a doctor of psychiatry’s doctor’s advice on landscaping. Were I forced to listen to a celebrity’s advice on parenting, I would opt for Jennifer Garner over Britney Spears. to differing views. It can also be affected by the writer's reputation as it exists independently from the message--his or her expertise in the field, his or her previous record or integrity, and so forth. The impact of ethos is often called the argument's 'ethical appeal' or the 'appeal from credibility.' Euphemism From the Greek, the use of good words, the Sanitary landfill – garbage dump use of a word or phrase that is less expressive At liberty – out of work offensive than another In the family way – pregnant or direct but considered less distasteful or Senior citizens – old people Man of leisure - hobo Euphony (opposite: cacophony) The subjective impression of pleasantness of sound I WANDER’D lonely as a cloud That floats on high o’er vales and hills, When all at once I saw a crowd, A host of golden daffodils; Beside the lake, beneath the trees, Fluttering and dancing in the breeze. ”Daffodils,” William Wordsworth Eye Rhyme Figurative Language Rhyme that appears correct from the spelling “Watch” and “latch,” good” and “food,” “bowl” and but is not so from the pronunciation “jowl,” “imply” and “simply,” “move” and “dove” The use of imaginative, non-literal words and phrases Figure of Speech An expression that uses language in a nonliteral way, such as a metaphor or a simile Flashback A literary or cinematic device in which an 12 earlier event is inserted into the normal chronological order of a narrative Foreshadowing the presentation in a work of literature of The imagery in the opening paragraph of “The hints and clues that tip the reader off as to Scarlet Ibis” leaves little doubt as to the outcome of Framework-Story A story within a story The Canterbury Tales, Frankenstein Free verse Verse that lacks regular rhyme and regular “Winter Poem” what is to come later in the work meter the story. by Nikki Giovanni once a snowflake fell on my brow and I loved it so much and I kissed it and it was happy and called its cousins and brothers and a web of snow engulfed me then I reached to love them all and I squeezed them and they became a spring rain and I stood perfectly still and was a flower Freytag’s Pyramid A diagram of the general structure of the plot of a story or drama Genre The classification of literary works according Epic, creative nonfiction, autobiography, biography, (ZHAHN-ruh) to common elements of content, form, or fiction (adventure, comedy, fantasy, horror, mystery, Hyperbole Over-exaggeration for effect technique romance, satire, science fiction, slave narrative, thriller, tragedy, etc.), diaries… “It was not a mere man he was holding, but a giant; or a block of granite. The pull was unendurable. The (hie-PUR-buh-lee) pain unendurable.” Ullman, “A Boy and a Man” Idiom An accepted phrase or expression having a meaning different from the literal reliable source Imagery Straight from the horse’s mouth – from a Words or phrases appealing to the senses— the descriptive diction—a writer uses to represent persons, objects, actions, feelings, and ideas 13 to get one’s goat – to anger a person to string someone along – to deceive someone “It was the clove of seasons, summer was dead but autumn had not yet been born, that the ibis lit in the bleeding tree. The flower garden was stained with rotting brown magnolia petals and ironweeds grew rank amid the purple phlox. The five o’clocks by the chimney still marked time, but the oriole nest in the elm was untenanted and rocked back and forth liked an empty cradle. The last graveyard flowers were blooming, and their smell drifted across the cotton field and through every room of our house, speaking softly the names of our dead.” Hurst, “The Scarlet Ibis” Inversion The placing of a sentence element out of its House beautiful (noun-adjective) normal position Lady fair (noun-adjective) Never have I seen such a mess (adverb auxiliary) “A damsel with a dulcimer/In a vision once I saw” (subject-verb-direct object) Coleridge Invocation An address to a deity for aid "Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns driven time and again off course, once he had plundered the hallowed heights of Troy." Homer, The Odyssey Irony A broad term referring to the recognition of a reality different from appearance Verbal Irony a figure of speech in what is said is the opposite of what is meant In a popular song from the ‘70’s, a farmer says to his wife who has abandoned him, “You picked a fine time to leave me, Lucille/with four hungry children and a crop in the field.” Dramatic Irony an incongruity or discrepancy between what In every cheesy horror flick, the killer is behind the a character says or thinks and what the door/in the closet/under the bed, while the character perceives and what the author while waiting for her date. And the audience gasps. reader knows to be true (or between what a intends the reader to perceive) Situation Irony A situation in which there is an incongruity between appearance and reality, or between unsuspecting victim applies pearly pink nail polish Donald Trump winning the lottery The ending of just about every M. Night Shyamalan film—except for maybe The expectation and fulfillment, or between the Happening, which was so bad, I really don’t actual situation and what would seem remember the very ending…oh yeah…France. appropriate The only good thing about it was John Leguizamo. Jargon Juxtaposition 1. Confused speech, resulting from the youth and old age mingling of several languages or dialects servants and nobles 2. nonsense or gibberish 3. the special love-sick Romeo and fiery Tybalt language of a group or profession the noisy public feast and the private whispers the act or instance of placing two things close Examples from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet: of the lovers together or side by side. This is often done in youth and old age order to compare/contrast the two, to show servants and nobles similarities or differences, etc. In literature, a love-sick Romeo and fiery Tybalt 14 juxtaposition occurs when two images that are otherwise not commonly brought the noisy public feast and the private whispers of the lovers together appear side by side or structurally close together, thereby forcing the reader to stop and reconsider the meaning of the text through the contrasting images, ideas, motifs, etc. Kenning A figurative phrase used in old Germanic Kennings from Beowulf are “the bent-necked Kennings are often picturesque metaphorical sea wood,” for a ship; the “swan road” and “the languages as a synonym for a simple noun. compounds Legend wood,” “the ringed prow,” “the foamy-necked,” “the whale road” for the sea A narrative or tradition handed down from the past; distinguished from a myth by having more of historical truth and perhaps less of the supernatural Leitmotif (LITE-moe-teef) A recurrent repetition of some word, phrase, situation, or idea, such as tends to unify a work through its power to recall earlier The idea of the mockingbird in To Kill a Mockingbird occurrences Literal Accurate to the letter; without embellishment One cannot truthfully say, “LITERALLY, Dude, my Litotes A form of understatement in which a thing is ( LI-toe-teez) affirmed by stating the negative of its teacher is so old, Shakespeare was her prom date!” "'Not a bad day's work on the whole,' he muttered, as he quietly took off his mask, and his pale, foxlike eyes glittered in the red glow of the fire. 'Not opposite a bad day's work.'" from Orzy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel “As you first see him he wonders frequently whether he is not without honor and slightly mad…” from Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and the Damned A few unannounced quizzes are not inconceivable. Logical Fallacies Fallacies are common errors in reasoning that will undermine the logic of your argument. Avoid these in writing and look for them in your reading. Ad Hominem Argument Literally “to the man”; attacks the character of the speaker or writer rather than his faithfulness of dogs because he has no faith at argument Begging the Question all in anything.” Assumes something to be true that needs proof. The arguer uses as proof the very Similar to false dilemma in that argument does not allow for shades of meaning, 15 “The reason George is so smart is because he is very intelligent.” argument that needs proving. Either/Or Fallacy “John Smith can’t tell us anything about the “Either we abolish cars, or the environment is doomed.” compromise, or intermediate cases Emotionally Charged Diction False Dilemma Uses vocabulary carrying strong connotative meaning, either positive or negative heart liberal who hates his mother, babies, apple pie, and the American way.” Uses a premise that presents a choice which does not include all the possibilities Glittering Generality “People hate politics because politicians often lie.” The premise that people hate politics is not necessarily true. Emotionally appealing words so closely associated with highly-valued concepts and “organic” supporting information or reason Rushing to a conclusion before gathering “working families,” the American Dream,” “your hard-earned freedom,” “motherhood,” beliefs that they carry conviction without Hasty Generalization “Senator Jones is a commie, pinko, bleeding- “Only motivated athletes become champions.” enough relevant facts Maybe not. There may be other factors in becoming champions, like good health, superior genes, etc. Post hoc ergo propter hoc (or Circular Reasoning) Attempts to prove something by showing one thing was caused by another merely because Texas won when I wore my lucky jersey. Texas won because I wore my lucky jersey. it followed that prior event in time (X happened because of Y, just because X happened after Y) Red Herring A diversionary tactic that avoids the key issues, often by avoiding opposing arguments rather than addressing them Straw Man Slippery Slope Logos The level of mercury in seafood may be unsafe, but what will fishermen do to support their families? Oversimplifies an opponent's viewpoint and then attacks that hollow argument People who don't support the proposed state minimum wage increase hate the poor. A faulty claim that taking one action inevitably leads to further negative actions The logic used to support a claim, it can also be the facts and statistics used to help support the argument. Logos (Greek for 'word') refers to the internal consistency of the message-the clarity of the claim, the logic of its reasons, and the effectiveness of its supporting evidence. The impact of logos on an audience is sometimes called the argument's logical appeal. 16 The state of Texas has deemed it necessary to fingerprint teachers. The next step will be blood and urine testing. Loose Sentence A sentence grammatically complete before I’m still hungry, although I just ate. the end Malapropism An inappropriateness of speech resulting The Nurse in Romeo and Juliet says “confidence” for (MAL-uh-PROP-iz-uhm) from the use of one word for another, which “conference.” Mrs. Malaprop (from whom the term resembles it is derived), a character in Sheridan’s The Rivals instructs, “illiterate him, I say, quite from your memory.” Maxim A concise statement, usually drawn from It is better to be alone than in bad company.” experience and instilling some practical George Washington advice Meiosis ( My –OE-sis) Intentional understatement for humorous or satiric effect "The unspeakable in full pursuit of the uneatable."(Oscar Wilde on fox hunting) "right-wing nutjobs" for Republicans; "leftwing pansies" for Democrats Memoir (MEM-wahr) Form of autobiographical writing dealing usually with the recollection of one who has been a part of or has witnessed significant Elie Wiesel’s Night; James McBride’s The Color of Water events Metaphor A comparison of two unlike things ”So excellent a king was, to this, Hyperion to a satyr…,” Shakespeare, Hamlet. In Act I, Scene 2, Hamlet compares his father, Claudius, to Hyperion, a Titan in classical mythology. The godlike view is enhanced by the comparison of Claudius to Hyperion's antithesis, the satyr, a creature half-goat and half-man, known for its drunken and lustful behavior—the behaviors of the new king, Claudius. Metonymy (Muh-TAH-nuh-mee) The substitution of the name of an object Referring to the queen as “the crown” itself Genesis 3:19 closely associated with a word for the word “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread,” Monologue A speech delivered to other characters Mood The atmosphere of a piece of writing. It is the Refer to the opening lines of James Hurst’s “The mind involved. It is different from the tone in ambience does Hurst create? prevailing feeling of a work, or the frame of that it will generally stay the same throughout the work. It sets an expectation of what is to follow. Think of the ambience in a restaurant and the details that create that ambience. In much the same way, a writer creates mood. Motivation The reasons, justifications, and explanations for the action of a character Myth refers to a body of folklore and legends that a particular culture believes to be true and that often use the supernatural to 1) interpret 17 Scarlet Ibis” (see imagery). What kind of mood or natural events and 2) explain the nature of the universe and humanity Narration One of the four types of composition, its purpose is to recount events Narrative An account of events; anything that is narrated Homer’s The Odyssey Narrative Poem A poem that tells story Narrator (see Point of Anyone who recounts a narrative; the View) storyteller Nobel Prize The Nobel Prize, established in Alfred Nobel’s Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird will in 1895, was first awarded in Peace, Literature, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, and Physics in 1901. The first Nobel Prize for Economics was awarded in 1968. The awards, conferred yearly, are widely regarded as the most prestigious award one can receive in said fields. Nom de plume (or pen A name adopted by a writer for professional William Sydney Porter became O. Henry name) use or to disguise his or her true identity Samuel Clemons became Mark Twain Novel Any extended fictional narrative almost To Kill a Mockingbird Lord of the Flies A Tale of Two Cities Candide Of Mice and Men Heart of Darkness always in prose Novella A short prose tale often characterized by moral teaching or satire Octave An eight-line stanza Ode A lyric poem of some length, usually of a serious or meditative nature and having an elevated style and formal stanzaic structure Onomatopoeia Words that by their sound suggest their Hiss, buzz, whirr, whistle meaning Oration A formal speech delivered in an impassioned manner Organization The structure of a piece of writing Overstatement Exaggeration for effect; hyperbole See hyperbole Oxymoron A figure of speech that combines two Bittersweet, jumbo shrimp, known secret, well- Parable An illustrative story teaching a lesson In Christian countries the most famous parables are Paradox A statement that may seem contradictory but (cousin to the oxymoron) may be well founded or true normally contradictory terms preserved ruins, current history, exact estimate those told by Christ, the best known of which is that of the Prodigal Son “I can resist anything except temptation. Less is more. “What a pity that youth must be wasted on the young.” 18 Oscar Wilde George Bernard Shaw Parallelism Using the same pattern of words to show that ( or Parallel structure) two or more ideas have the same level of the road, crashed into a barrier and popped me phrase, or clause level Mockingbird “The tire bumped on gravel, skeetered across like a cork onto pavement”(37). Lee, To Kill a importance. This can happen at the word, “…with his statues, his recognizances, his fines, his double vouchers, his recoveries: is this the fine of his fines…” Shakespeare, Hamlet Paraphrase A restatement of an idea (typically for the purposes of clarity) in such a way as to retain the meaning while changing the diction and form. Parenthesis An explanatory remark inside a statement, frequently separated from it by parenthesis. However, any comment—whether a word, phrase, clause, sentence, or paragraph—that is an interruption of the immediate subject is considered parenthetical. Pathos The emotional or motivational appeals, it uses Sarah McLachlan’s commercial about animal abuse vivid language, emotional language and relies heavily on pathos. numerous sensory details. Pathos (Greek for 'suffering' or 'experience') is often associated with emotional appeal. But a better equivalent might be 'appeal to the audience's sympathies and imagination.' An appeal to pathos causes an audience not just to respond emotionally but to identify with the writer's point of view-to feel what the writer feels. In this sense, pathos evokes a meaning implicit in the verb 'to suffer'--to feel pain imaginatively.... Perhaps the most common way of conveying a pathetic appeal is through narrative or story, which can turn the abstractions of logic into something palpable and present. The values, beliefs, and understandings of the writer are implicit in the story and conveyed imaginatively to the reader. Pathos thus refers to both the emotional and the imaginative impact of the message on an audience, the power with which the writer's message moves the audience to decision or action. Periodic Sentence a sentence that is not grammatically complete Though generally a tolerant sort, deceit or treachery Persona Literally, a mask. The term is widely used to The character of Huck Finn allowed Mark Twain to and through whom the narrative is told—a otherwise would not have been as palatable to many until its end refer to a “second self” created by an author 19 she could never forgive. communicate many of his political views which voice not directly the author’s but created by of his Southern readers. the author and through whom the author speaks. Personification A figure of speech that lends human qualities to animals, idea s, and inanimate objects "Because I could not stop for Death-He kindly stopped for me-- The Carriage held but just Ourselves-And Immortality." Dickinson Persuasion A major type of writing whose purpose is to convince others of the wisdom of a certain line of action. Plagiarism the unauthorized use or close imitation of the language and thoughts of another author and the representation of them as one's own original work Play a dramatic work intended for performance by Plot By Aristotle’s definition, “the imitation of an actors on a stage Romeo and Juliet A Raisin in the Sun action,” the “arrangement of the incidents” of a story which necessitates a beginning, a middle, and an end Poet Laureate (LAWR-ee-it) 1. a poet honored for achievement 2a. a poet Some American Poets Laureate: Ted Kooser, Billy appointed for life by an English sovereign as a Collins, Rita Dove, Robert Frost expected to compose poems for court and Hughes, Robert Bridges, William Wordsworth member of the royal household and formerly national occasions b. a poet appointed Some British Poets Laureate: John Dryden, Ted annually by the United States Library of Congress as a consultant and typically involved in the promotion of poetry Point of View First-person Second-person The perspective from which a story is told Pronouns frequently used by narrator: Narration in which a character tells the story I, me, my, mine, our, ours Narration in which the narrator tells the story You, your, yours to another character using “you,” so that the story is told through the addressee’s point of view. Second person is the least commonly used POV in fiction. Many of the stories in Lorrie Moore's book "Self-Help" are written in the second person, as is Tom Robbins's "Half Asleep in Frog Pajamas," which begins: "The day the stock market falls out of bed and breaks its back is the worst day of your life. Or so you think. It isn't the worst day of your life, but you think it is." 20 Third-person limited Narration in which the narrator, an outsider, He, him, his, she, her, hers, it, its, their, theirs knows the thoughts and feelings of only one character Third-person Omniscient Narration in which the narrator knows the He, him, his, she, her, hers, it, its, their, theirs thoughts and feelings of all the characters Polysyndeton The inclusion of conjunctions in close "Let the whitefolks have their money and power and (pol-ee-SIN-di-ton) succession, esp. where one typically uses segregation and sarcasm and big houses and schools commas and lawns like carpets, and books, and mostly-mostly--let them have their whiteness.” Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings counter term: asyndeton Précis (PREY-see) A concise summary of a text Preface An introduction to a book written by the author. While not a part of the story, it typically provides insight into the text and acknowledgments those who helped and/or inspired the writer in the creation of the book. Prologue A prologue is to a play what a preface is to a book, minus the acknowledgements. Prose Ordinary speech or writing as distinguished Pun A humorous play on words that may be based words or between different senses of the same from verse "Ask for me tomorrow, and you shall find me a grave man...." Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet on similarities in sound between two or more or derivative words. Tom Swifties "The doctor had to remove my left ventricle," said Tom half-heartedly. "I have a split personality," said Tom, being frank. Quatrain A stanza of four lines Redundancy Excessive repetition Repetition Reiteration of a word, sound, phrase, or idea. Rhetoric The art of persuasion; the art of speaking or (RET-er-ik) writing effectively Rhetorical Question A question meant to elicit discussion rather "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?" But where will Europe's latter hour /Again find than a definitive answer. If answered, the implied answer is yes, no, or never. Shakespeare, Sonnet 18 Wordsworth's healing power? (Matthew Arnold. "Memorial Verses") (The implied answer is "Never! Wordsworth was one-of-a-kind as far as "healing power" goes!") Satire Humorous or witty writing in which human folly or vice is attacked for the purpose of improving human institutions or humanity. Scene A subdivision of a play; a division of an act Short Story A short piece of prose fiction, briefer than a 21 novella; short story can typically be read in a sitting “Show, don’t tell.” A directive to writers of fiction to engage/involve the reader through action, dialogue, imagery, etc., as opposed to lifeless narration. Soliloquy A speech delivered while the speaker is alone. Protagonist The central character of a drama, novel, short Sonnet A poem typically consisting of fourteen lines counter term: antagonist story, or narrative poem Odysseus in The Odyssey, Jonah in The Giver and a given rhyme scheme depending on the type of sonnet Source a document (or organization) from which Stage Directions Directions, usually in italics, added to a script Stanza a fixed number of lines of verse forming a Structure The planned framework of a piece of Style The use of language that is unique to each information is obtained to instruct actors how to carry out a scene “Enter OPHELIA, distracted,” Shakespeare, Hamlet unit of a poem literature author, much like a fingerprint. It results from the rhetorical use of such devices as diction, imagery, repetition, and syntax. Syllogism (SIL-uh-jiz-uhm) A formula for presenting a logical argument, 1. No dogs have wings. This animal is not a dog. consisting of a major premise, a minor 2. This animal has wings. premise, and a conclusion 3. Symbol Something that retains its identity while Winter often represents death, loss, or emptiness, Synecdoche A figure of speech in which a part of (si-NEK-duh-kee) representing something else while spring represents birth, renewal, hope. something represents the entire thing (the deck!” refers to the sailors not just their hands, part for the whole) thankfully. Syntax A ship captain’s command, “All hands on The rule-governed arrangement of words in sentences Some folks refer to cars as their “wheels.” The syntactical rules for today’s English dictate that we say, “My dogs are fabulous” rather than “Fabulous are dogs my.” Theme The central idea about which one writes or speaks. Theme cannot be expressed as a simple subject or an idea, but must include a predicate. Through reading a work, then, one determines the writer’s point and can then fill Examples for Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet: Rash actions lead to tragic consequences. Old grudges against those we hate the most can ultimately destroy those we love the most. in the blanks: The writer is saying _____ (writer’s opinion) about _____ (the subject of the piece). Thesis The position a writer or speaker takes and While arguably our most intellectual and supports in a rhetorical situation contemplative president, Thomas Jefferson remains 22 our most enigmatic, given his ambivalence on the subject of slavery. Stylistic/clichéd NEVERS: Tone Things are not always as they seem. Actions speak louder than words. The writer’s attitude toward his subject. Awestruck, belligerent, compassionate, derisive, Think of this also as the attitude the writer incredulous, philosophical, reverent, self-pitying, through the writer’s use of rhetorical devices Stylistic/clichéd NEVERS: In general, a work that deals with the idea Antigone, Julius Caesar, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, Othello wants the audience to take. Tone is conveyed as diction, imagery, repetition, and syntax. Tragedy In this paper, I will write about… that through fate, human failure, irony, or simply the human condition, man is doomed. skeptical, world-weary. good, bad, happy, sad The tragedy’s focus and ultimate triumph lies in how the hero (typically of high birth and noble character) meets his certain failure. Tragic Flaw The idea that the tragic hero possesses an inherent quality that ultimately brings about his downfall. The trait, however, need not If one buys the theory, the following would be considered tragic flaws: Romeo’s rashness always be a flaw, as with Antigone’s duty to Othello’s jealousy God and family. In such tragedies, outside Hamlet’s indecision forces working against the hero bring the character trait into play; given the right—or wrong, as it may be—circumstances, the hero meets his untimely demise. So the idea of a tragic hero is somewhat controversial. Tudor The royal house that ruled England from 1485 to 1603: Henry VII (1485-1509), Henry VIII (1509-1547), Edward VI (15471553), Mary I (1553-1558), and Elizabeth I (1558-1603) Verse 1) A unit of poetry, a stanza 2) poetry Sources http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/ http://courses.durhamtech.edu/perkins/aris.html http://grammar.about.com http://www.merriam-webster.com http://orwell.ru/library/ http://owl.english.purdue.edu/ http://en.wikipedia.org http://wordnet.princeton.edu Harmon, William and Hugh Holman. A Handbook to Literature 9th ed Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Prentice Hall 2003 23 Levels of Questions Level 1: On the Line Readers find concrete, factual information directly in the text. Readers can literally put their fingers on the answer in the text. Key questions include who, what, where, and when. Level 2: Between the Lines + Readers reason, compare, and contrast. This level is more abstract, thoughtful, analytical, interpretive. Readers still consider the text, but cannot point to the literal answer in the text. They can, however, point to hints and suggestions in the text that lead to answers. Key questions include how and why. Key verbs might include represents, suggests, personifies, alludes to, etc. Level 3: Beyond the Lines + This level is super-abstract. Readers think outside of the text, discussing ideas found in the text but not necessarily discussing the text itself. Readers make connections between the text and themselves, the rest of the world, other pieces of literature, film, etc. Readers evaluate, synthesize, create information, using the text as a springboard. Key questions include: Why is this text relevant? What does is have to do with me? What do I think of this text and why? What does this text say about ideas or issues found in the text such as goodness, humanity, relationships, etc.? 24 Tone Words 1. accusatory - charging of wrong doing 2. apathetic - indifferent due to lack of energy or concern 3. awe - solemn wonder 4. bitter - exhibiting strong animosity as a result of pain or grief 5. cynical - questions the basic sincerity and goodness of people 6. condescension; condescending - a sense of superiority 7. callous - unfeeling, insensitive to feelings of others 8. contemplative - studying, thinking, reflecting on an issue 9. critical - finding fault 10. choleric - hot-tempered, easily angered 11. contemptuous - showing or feeling that something is worthless or lacks respect 12. caustic - intense use of sarcasm; stinging, biting 13. conventional - lacking spontaneity, originality, and individuality 14. disdainful - scornful 15. didactic - author attempts to educate or instruct the reader 16. derisive - ridiculing, mocking 17. earnest - intense, a sincere state of mind 18. erudite - learned, polished, scholarly 19. fanciful - using the imagination 20. forthright - directly frank without hesitation 21. gloomy - darkness, sadness, rejection 22. haughty - proud and vain to the point of arrogance 23. indignant - marked by anger aroused by injustice 24. intimate -very familiar 25. judgmental - authoritative and often having critical opinions 25 26. jovial - happy 27. lyrical- expressing a poet’s inner feelings; emotional; full of images; song-like 28. matter-of-fact - accepting of conditions; not fanciful or emotional 29. mocking - treating with contempt or ridicule 30. morose - gloomy, sullen, surly, despondent 31. malicious - purposely hurtful 32. objective - an unbiased view-able to leave personal judgments aside 33. optimistic - hopeful, cheerful 34. obsequious- polite and obedient in order to gain something 35. patronizing – with an air of condescension 36. pessimistic - seeing the worst side of things; no hope 37. quizzical- odd, eccentric, amusing 38. ribald - offensive in speech or gesture 39. reverent - treating a subject with honor and respect 40. ridiculing - slightly contemptuous banter; making fun of 41. reflective - illustrating innermost thoughts and emotions 42. sarcastic - sneering, caustic 43. sardonic - scornfully and bitterly sarcastic 44. satiric - ridiculing to show weakness in order to make a point, teach 45. sincere - without deceit or pretense; genuine 46. solemn - deeply earnest, tending toward sad reflection 47. sanguine - optimistic, cheerful 48. whimsical - odd, strange, fantastic; fun 26 CHARACTER Authors reveal what characters are like in two general ways: directly or indirectly. In the direct method, the author simply tells the reader what the characters are like. When the method of revealing the characters is indirect, however, the author shows us, rather than tells us, what the characters are like through what they say about one another, through details (dress, bearing, looks), and through their thoughts, deeds, and speech. Characters who remain the same throughout the work are considered static, while those who change over the course of the work are considered dynamic. Dynamic characters, especially main characters, typically grow in understanding. The climax in this growth is called an epiphany, a term that Irish author James Joyce used to describe a sudden revelation of truth experienced by a character. The term comes from the Bible and describes the Wise Men’s first perception of Christ’s divinity. ACTIVE READER: You can ask many revealing questions about characters and the ways they are developed. 1. Are they flat, round, static, or dynamic? 2. If they change, how and why do they change? 3. What steps do they go through to change? 4. What events or moments of self-revelation produce these changes? 5. Does what they learn help or hinder them? 6. What problems do they have? 7. How do they attempt to solve their problems? 8. What types of stock characters do they represent? (ex: repressed housewife, mad scientist) 9. If the characters are complex, what makes them complex? 10.Do they have traits that contradict one another and therefore caused internal conflicts? 11.Do they experience epiphanies? When? Why? 12.What does the epiphany reveal to the character and to us? 13.How does one character relate to others in the novel? 14.Do they have speech mannerisms, gestures, or modes of dress that reveal their inner selves? 15.Comment on the emotional state of the characters. Keep in mind: The conflicts created through the plot directly affect character development. 27 SETTING Setting includes several closely related aspects of a work of fiction. First, setting is the physical sensuous world of the work. Second, it’s the time in which the action of the work takes place. And third, it’s the social environment of the characters: the manners, customs, and moral values that govern the characters’ society. A fourth aspect—atmosphere—is largely, but not entirely, an effect of setting. Issues to consider when thinking about the setting of a novel: Questions about place: Get the details about the physical setting clear in your mind. Where does the action take place? On what planet, in what country or locale? What sensuous qualities does the author give to the setting? That is, what does it look like, sound like, smell like, feel like? DO you receive a dominant impression about the setting? What impression, and what caused it? Once you have established the above, what relationship does the place have to characterization and theme? In what ways does the physical, or external, setting correspond to or contrast with the psychological, or internal, landscape? In some fiction, geographic location may be of importance. Questions about time: Three kinds of time occur in fiction. First, at what period in history does the action take place? Many stories occur during historical events that affect the characters and themes in important ways. Second, how long does it take for the action to occur? How does the author use the passage of time as a thematic and structuring device? Third, how is the passage of time perceived? Time may seem to move very slowly or quickly, depending on a character’s state of mind. Thus, our recognition of a character’s perception of time helps us understand the character’s internal conflicts and attitudes. Questions about atmosphere: Atmosphere refers to the emotional reaction we, and usually the character, have to the setting of the work. Sometimes the atmosphere is difficult to define, but it is often found or felt in the sensuous quality of the setting. ACTIVE READER: Use the following strategies when analyzing setting. 1. Mark the most extensive or important descriptions of physical place. Underline the most telling words and phrases. 2. Characterize physical locales, such as houses, rooms and outdoor areas. 28 3. Explain the relationship of one or more of the main characters to the physical place. Explain the influence that place exerts on the characters. 4. Arrange the main events in chronological order. Indicate when each main event occurs. 5. Mark passages where a character’s emotional state effects the way the passage of time is presented to us. 6. List the historical, factual circumstances and characters that occur in the work. Explain their importance and their relationship with themes and characters in the book. 7. Lit the patterns of behavior that characterize the social environment of the work. 8. Mark the scenes in which the author or characters express approval or disapproval of these patterns of behavior. 9. Explain the influence one or more of these patterns have on a character or characters. 10.Mark sections that contribute to atmosphere. Underline key words and phrases. 11.List the traits of atmosphere. 29 PLOT The Nature of Fiction: As a descriptive term, “fiction” is misleading, for although fiction does often include made-up or imaginary elements, it has the potential for being “true”: true to the nature of reality, true to human experience. Both writers of history and fiction attempt to create a world that resembles the multiplicity and complexity of the real world. What makes fiction different, of course, is its ability to build conflict, to be imaginative, to order events, and be dramatic. Writers of fiction celebrate their separateness, distinctness, and importance of individuals and individual differences. They assume that human experiences, whatever they are, and whenever they occur, are intrinsically important and interesting. Additionally, writers of fiction see reality as welded to psychological perception, as refracted through the minds of individuals. Writers arrange fictional events into patterns (plot), such as that in Freytag’s Pyramid. ACTIVE READER: Probably the most revealing question one can ask about a work of literature is: What conflicts does it dramatize? Since that question might be a bit broad and overwhelming, the following sub-questions can break it down for you: What is the main conflict? What are the minor conflicts? How are all the conflicts related? What causes the conflicts? Which conflicts are external and which are internal? Who is the protagonist? What qualities or values does the author associate with each side of the conflict? Where does the climax occur? Why? How is the main conflict resolved? Which conflicts go unresolved? Why? Additional strategies for thinking about plot: 1. List the qualities of the protagonist(s) and antagonist(s). 2. Draw a two-column chart on a sheet of notebook paper. On the left side, list the external conflicts of the work. On the right side, list the internal conflicts. Draw a line connecting 30 the external and internal conflicts that seem related. 3. List the key conflicts. For each conflict, list the ways in which the conflict has been resolved, if it has. Mark the conflicts that are left unresolved. 4. List the major structural units of the work (chapters, scenes, parts). Summarize what happens in each part. What relationship does the action or conflicts have to the structure? 5. Are certain episodes narrated out of chronological order? What is the effect of the arrangements of episodes? 6. Are certain situations repeated? If so, what do you make out of the repetitions? 7. Describe the qualities that make the situation at the beginning unstable. Describe the qualities that make the conclusion stable, if in fact it is. 8. List the causes of the unstable situations at the beginning and throughout the work. 31 THEME The key questions for eliciting a work’s themes are: What is the subject? (What is the work about?) What is the theme? (What does the work say about the subject?) Finally, in what direct and indirect and indirect ways does the work communicate the theme(s)? One strategy for discovering a work’s theme(s) is to apply frequently asked questions about areas of human experience, such as the following: Human nature: What image of human kind emerges from the work: Are people, for example, generally good? …deeply flawed? The nature of society: does the author portray a particular society or social scheme as lifeenhancing or life-destroying? Are characters we care about in conflict with their society? If so, in what ways do they conflict with that society? Do these characters want to escape from it? What causes and perpetuates this society? If the society is flawed, how is it flawed? Human freedom: what control over their lives do the characters have? Do they make choices in complete freedom? Are they driven by forces beyond their control? Does Providence or some grand scheme govern history, or is history simply random and arbitrary? Ethics: what are the moral conflicts of the work? Are they clear cut or ambiguous? That is, is it clear to us what is right or what exactly is wrong? When moral conflicts are ambiguous in a work, right often opposes right, not wrong. (Don’t forget to examine these from the perspective of every character.) What rights are in opposition to one another? If right opposes wrong, does right win in the end? To what extent are characters to blame for their actions? Finally, another, strategy for discovering a work’s theme(s) is to answer this question: Who serves as the moral center of the work? The moral center is the one person whom the author vests with right action and right thought (that is, what the author seems to think is the right action and the right thought)—the one character who seems clearly good and who often serves to judge the other character(s). 32 Additional strategies to develop a thematic statement: 1. List the subject or subjects for the work. For each subject, see if you can state a theme in a complete sentence. Put a check next to the ones that seem the most relevant. 2. Explain how the title, subtitle, epigraph, titles, and/or names of characters may be related to theme. 3. Describe the work’s depiction of human behavior. 4. Describe the work’s depiction of society. Explain the representation of social ills and how they might be corrected or addressed. 5. List the moral issues raised by the work. 6. Name the character who is the moral center of the work. List the traits of this character that support your choice. 7. Mark statements by the writer or characters that seem to state or imply themes. 8. Does the theme of the work reinforce values you hold, or does it to some degree challenge them? 33 TPCASTT Term Title Explanation Examine the title before reading the poem. What do you predict the poem will be about? Paraphrase Translate the poem into your own words. Connotation Contemplate the poem for meaning beyond the literal. Examine literary devices. Examine specific words and phrases that contribute to the meaning of the poem. Note your gut instincts/emotional responses. UNDERLINE, CIRCLE, DRAW ARROWS BETWEEN RELATED IDEAS/IMAGES, ETC. LABEL, LABEL, LABEL…AND MAKE NOTATIONS ABOUT MEANINGS AND CONNECTIONS, ETC. Attitude Observe both the speaker’s and the poet’s attitude (tone). Remember, the poet and the speaker are seldom the same person. Examine specific word choice/diction. Shifts Note shifts in the speakers and in attitudes. Rarely does a poet begin and end in the same place. Look for key words (but, yet, however, although) Punctuation (dashes, periods, colons, ellipses) Stanza divisions Change in line and/or stanza length Irony Effect of structure on meaning Changes in sound Changes in diction (i.e., slang to formal) Title Examine the title again, this time on an interpretive level. Theme Write a thematic statement. What message is the poet trying to convey? What point is he trying to make? Remember the three requirements for your thematic statement: a. It must be universal. b. It must be arguable. c. You must be able support it with the text of the poem. 34 SOAPS (A general mnemonic for any type of writing: what you should address immediately) S = Speaker - Who is speaking? What do you know about this person? What is the perspective and point of view? O = Occasion - What are the time and place of the situation? How do they affect the situation? How did they encourage the writing? A = Audience - Other than the reader, to whom is the writer directing this work? Is it a type of person? P = Purpose - Why is the writer writing (or speaker speaking)? S = Subject - What is the general topic? Is there more than one subject? Does the piece purport to be about one topic but is really about another? DIDLS – Elements of Tone D = Diction: word choice for effect I = Imagery: vivid appeals to understanding through the senses D = Details: facts that are included or omitted L = Language: the overall use of language, such as formal, clinical, jargon S = Syntax: Sentence structure and how it affects the reader’s attitude 35 Expanding DIDLS: Analyzing Tone in Prose and Poetry Diction 1. Circle all the words you do not know. 2. Underline words that seem especially meaningful or well-chosen. For each word, explain denotations and connotations in the margin. 3. Underline any word play such as double meanings and puns. In the margin, explain what the word play adds to the sense of the passage. 4. Underline any uses of unusual words. In the margin, explain what qualities and meaning these words add to the passage. 5. Explain how the choice of words contributes to the speaker’ tone. Imagery (and Figurative Language) 1. Mark the descriptive passages. For each image, name the sense appealed to. Characterize the dominate impression these images make. 2. Explain the relationship of descriptive images to the speaker’s state of mind. 3. Note any progression in the descriptive images; for example, from day to night, hot to cold, soft to loud, color to color, slow to fast, etc. 4. Explain how the descriptive images help create atmosphere and mood. Slow movements for example, are conducive to melancholy, speed to exuberance and excitement. 5. Mark the similes and metaphors in the passage. Explain the implications of the analogies. 6. Mark any personification in the passage. Explain the implications of the analogies. 7. List the senses appealed to in each analogy. Make note of any links to meaning conveyed through these appeals. Details 1. What details are included in the passage that reveal the speaker’s attitude about the subject? 2. What details are omitted in the passage that reveal the speaker’s attitude about the subject? 3. How does the inclusion or exclusion of details in the passage help create tone? Language 1. Identify the level of diction (formal, informal, colloquial, slang, dialect, etc.) What does the level of diction have to do with the speaker’s attitude towards the subject? Syntax 1. Examine the position of words, paying close attention to such placements as first order, last order, 36 isolated words, inverted word order. Consider why the writer made these choices. 2. How does the sentence structure affect the reader’s attitude? Plagiarism: A Very Big Deal Wikipedia defines plagiarism as “the passing off of another person's work as if it were one's own, by claiming credit for something that was actually done by someone else. It is not plagiarism to use wellknown or common sense facts, such as “Thomas Jefferson wrote The Declaration of Independence.” The most blatant examples of plagiarism I find in the classroom include students 1. Turning in papers written entirely by someone else with his/her name on it, the “someone else” ranging from another students to overzealous parents to anonymous writers on commercial websites 2. Cutting and pasting from several papers 3. Copying other students’ work Perhaps not so blatant but still deliberate plagiarism includes students: 4. Copying sentences from another source while changing a few of the words 5. Paraphrasing without giving credit to original source 6. Using the questionable “brain matter” of sources such as Sparknotes for their literary analysis instead of reading the book Why students plagiarize: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Laziness/failure to manage time Lack of knowledge/ability Stress Insecurity/perceived lack of knowledge/ability Not realizing they’re plagiarizing Not taking assignment seriously Have never been caught/don’t care if they’re caught Why plagiarism doesn’t work in the long run: 1. Loss of trust is a very big deal. 2. You need to be evaluated in what you can do. When we’re studying a new concept, I need to know if you got it, and more importantly, YOU need to know if you got it. 3. Cutting and pasting is for little kids. Penalties in this class: 1. A zero on the assignment; this could result in a failing grade for the class. Depending on your grade for the remainder of the course, it could also result in a failing grade for the term, semester, or course. If you’re a senior, it could mean you don’t graduate. 2. Possible failure to gain entrance to or expulsion from the National Honors Society. 3. My refusal to recommend you to any organizations and/or universities. 37 Possible penalties in and out of the classroom: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Zeros on assignments/failing grades Expulsions from classes/universities Public distrust/humiliation Loss of job/income Jail time How to avoid plagiarism 1. Simple: Do your own work. 2. Document, document, document. When doing research for an English class, this means using the MLA (Modern Language Association) format. 3. Don’t procrastinate. 4. Attend tutorials. 5. Trust yourself. 38 Posted on Fri, Jun. 03, 2005 IN MY OPINION Chris Cecil, plagiarism gets you fired By Leonard Pitts Jr. D ear Chris Cecil: Here's how you write a newspaper column. First, you find a topic that engages you. Then you spend a few hours banging your head against a computer screen until what you've written there no longer makes you want to hurl. Or, you could just wait till somebody else writes a column and steal it. That's what you've been doing on a regular basis. Before Tuesday, I had never heard of you or the Daily Tribune News, in Cartersville, Ga., where you are associate managing editor. Then one of my readers, God bless her, sent me an e-mail noting the similarities between a column of mine and one you had purportedly written. Intrigued, I did a little research on your paper's website and found that you had ''written'' at least eight columns since March that were taken in whole or in part from my work. The thefts ranged from the pilfering of the lead from a gangsta rap column to the wholesale heist of an entire piece I did about Bill Cosby. In that instance, you essentially took my name off and slapped yours on. On March 11, I wrote: I like hypocrites. You would, too, if you had this job. A hypocrite is the next best thing to a day off. Some pious moralizer contradicts his words with his deeds and the column all but writes itself. It's different with Bill Cosby. On May 12, you ''wrote:'' I like hypocrites. You would, too, if you had this job. A hypocrite is the next best thing to a day off. Some pious moralizer contradicts his words with his deeds and the column all but writes itself. It's different with Bill Cosby. The one that really got me, though, was your theft of a personal anecdote about the moment I realized my mother was dying of cancer. ''The tears surprised me,'' I wrote. ''I pulled over, blinded by them.'' Seven days later, there you were: ``The tears surprised me. I pulled over, blinded by them on central Kentucky's I-75.'' Actually, it happened at an on-ramp to the Artesia Freeway in Compton, Calif. I've been in this business 29 years, Mr. Cecil, and I've been plagiarized before. But I've never seen a plagiarist as industrious and brazen as you. My boss is calling your boss, but I doubt you and I will ever speak. Still, I wanted you to hear from me. I wanted you to understand how this feels. Put it like this: I had a house burglarized once. This reminds me of that. Same sense of violation, same apoplectic disbelief that someone has the testicular fortitude to come into your place and take what is yours. Not being a writer yourself, you won't understand, but I am a worshiper at the First Church of the Written Word, a 39 lover of language, a student of its rhythm, its music, its violence and its power. My words are important to me. I struggle with them, obsess over them. Show me something I wrote and like a mother recounting a child's birth, I can tell you stories of how it came to be, why this adjective here or that colon there. See, my life's goal is to learn to write. And you cannot cut and paste your way to that. You can only work your way there, sweating out words, wrestling down prose, hammering together poetry. There are no shortcuts. You are just the latest in a growing list of people -- in journalism and out -- who don't understand that, who think it's OK to cheat your way across the finish line. I've always wanted to ask one of you: How can you do that? Have you no shame? No honor or pride? How do you face your mirror knowing you are not what you purport to be? Knowing that you are a fraud? If your boss values his paper's credibility, you will soon have lots of free time to ponder those questions. But before you go, let me say something on behalf of all of us who are struggling to learn how to write, or just struggling to be honorable human beings: The dictionary is a big book. Get your own damn words. Leave mine alone. P.S.: Chris Cecil was fired Thursday by Daily Tribune News Publisher Charles Hurley, immediately after he learned of the plagiarism. 40 Using POWER when you write under pressure FROM PANICKED TO EMPOWERED P = Prewrite O = Organize Get as many ideas down as quickly as you can without thinking about order or form Organize all of your ideas you hope to include in your essay Begin putting all of your ideas by order of W = Write importance, beginning with introduction (including thesis), body paragraphs, and conclusions Re-read what you have written. Make changes that E = Edit you feel will make your paper more effective. Check your concrete detail/commentary ratio. R = Revise Write your final draft. 41 QUADCARDS baneful 42 Phrase Toolbox Phrases are groups of words that do not contain both a subject and a verb. Collectively, the words in each phrase function as a single part of speech. Type of Phrase Absolute Function/Composition A modifier that somewhat resembles a completes sentence Consists of a subject and a partial verb (omitting an auxiliary verb—always a form of the verb to be—is, are, was, or were) Examples Appositive Gerund Renames or identifies an adjacent noun or pronoun Consists of the appositive noun plus any of its modifiers. A gerund is a verbal that ends in -ing and functions as a noun. A gerund phrase is a type of verb phrase that begins with a verb in its -ing form and is followed by modifiers. 43 The safe-cracker lurked, his fingers twitching with anticipation. His head down, his dreams dashed, the little-leaguer trudged wearily to the dugout. The students came to class prepared, notebooks and pens in hand. Glenn, an avid outdoorsman, enjoys poetry as well as fishing. Jake, the musclebound Golden Retriever, is Glenn’s faithful hunting companion. Cooking as a hobby is something Maxine never considered; she has McDonald’s and the local deli on speed dial. Turning in assignments late can be costly. Additional Information Most absolutes phrases begin with a possessive pronoun (my, your, his, her, its, our, or their). Sometimes, however, the possessive is implied, as in the third example. When it adds nonessential information, it is set off by commas. Since a gerund functions as a noun, it occupies some positions in a sentence that a noun ordinarily would, for example: subject, direct object, subject Infinitive A verbal consisting of the word to plus a verb (in its simplest "stem" form) and functioning as a noun, adjective, or adverb. Participial phrase A verb form (past or present) functioning like an adjective. Consists of the participle plus its modifiers. Prepositional phrase A prepositional phrase is a group of words beginning with a preposition and ending with a noun or pronoun (called its object). Prepositional phrases function in a sentence as adjectives or adverbs. Consists of a preposition plus its objects and its modifiers . 44 My dream is to write the great American novel. Some feel that to retire is to die, while others feel that to retire is to live a second time. I implore you to learn the difference between the infinitive “to” and the prepositional “to.” I invited Sheila to go to the movies with me. Mesmerized by the music, Sara drifted into a dream world. Matt, swimming for his life, fled from the crocodiles. Muriel jumped at the offer, intrigued. I went down the street, around the corner, to the store, to buy a quart of milk. “Over the river and through the wood To Grandfather's house we go.” complement, and object of preposition. The infinitive may function as a subject, direct object, subject complement, adjective, or adverb in a sentence. The first word in the phrase is always the participle itself. THE ESSENCE OF STYLE/LITERARY ANALYSIS (What to address in an essay on style analysis) STEP 1 What did the author do with the piece? (What is the purpose, theme, message?) STEP 2 How did the author do it? (What techniques/stylistic devices did the author use?) STEP 3 Why is the way those techniques were used especially fitting for illustrating what the author did? (How do steps 1 and 2 relate?) 45 46 47 48 49 50