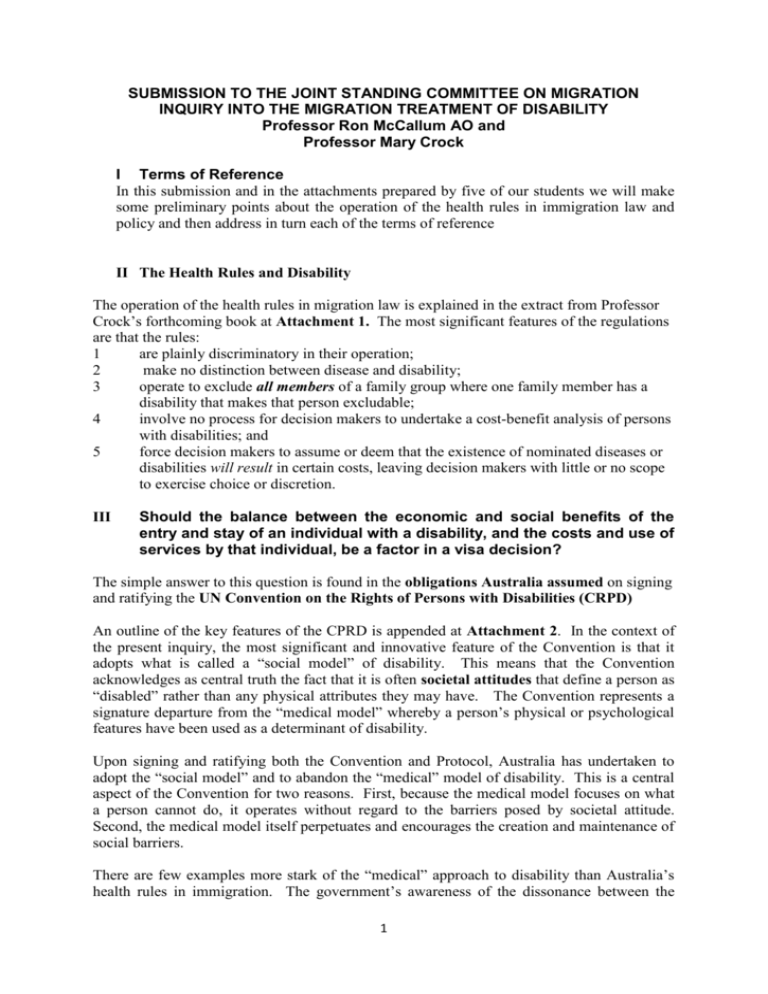

Migration Law - The University of Sydney

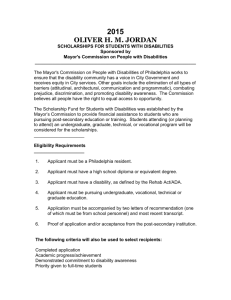

advertisement