Feminist Lens

advertisement

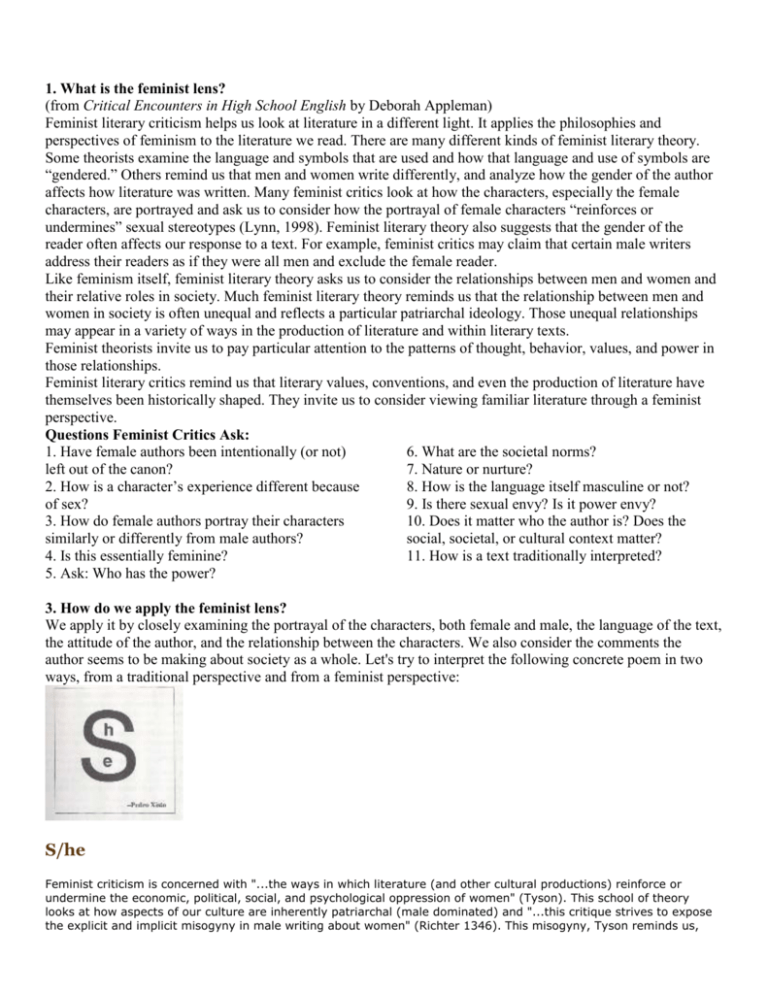

1. What is the feminist lens? (from Critical Encounters in High School English by Deborah Appleman) Feminist literary criticism helps us look at literature in a different light. It applies the philosophies and perspectives of feminism to the literature we read. There are many different kinds of feminist literary theory. Some theorists examine the language and symbols that are used and how that language and use of symbols are “gendered.” Others remind us that men and women write differently, and analyze how the gender of the author affects how literature was written. Many feminist critics look at how the characters, especially the female characters, are portrayed and ask us to consider how the portrayal of female characters “reinforces or undermines” sexual stereotypes (Lynn, 1998). Feminist literary theory also suggests that the gender of the reader often affects our response to a text. For example, feminist critics may claim that certain male writers address their readers as if they were all men and exclude the female reader. Like feminism itself, feminist literary theory asks us to consider the relationships between men and women and their relative roles in society. Much feminist literary theory reminds us that the relationship between men and women in society is often unequal and reflects a particular patriarchal ideology. Those unequal relationships may appear in a variety of ways in the production of literature and within literary texts. Feminist theorists invite us to pay particular attention to the patterns of thought, behavior, values, and power in those relationships. Feminist literary critics remind us that literary values, conventions, and even the production of literature have themselves been historically shaped. They invite us to consider viewing familiar literature through a feminist perspective. Questions Feminist Critics Ask: 1. Have female authors been intentionally (or not) 6. What are the societal norms? left out of the canon? 7. Nature or nurture? 2. How is a character’s experience different because 8. How is the language itself masculine or not? of sex? 9. Is there sexual envy? Is it power envy? 3. How do female authors portray their characters 10. Does it matter who the author is? Does the similarly or differently from male authors? social, societal, or cultural context matter? 4. Is this essentially feminine? 11. How is a text traditionally interpreted? 5. Ask: Who has the power? 3. How do we apply the feminist lens? We apply it by closely examining the portrayal of the characters, both female and male, the language of the text, the attitude of the author, and the relationship between the characters. We also consider the comments the author seems to be making about society as a whole. Let's try to interpret the following concrete poem in two ways, from a traditional perspective and from a feminist perspective: S/he Feminist criticism is concerned with "...the ways in which literature (and other cultural productions) reinforce or undermine the economic, political, social, and psychological oppression of women" (Tyson). This school of theory looks at how aspects of our culture are inherently patriarchal (male dominated) and "...this critique strives to expose the explicit and implicit misogyny in male writing about women" (Richter 1346). This misogyny, Tyson reminds us, can extend into diverse areas of our culture: "Perhaps the most chilling example...is found in the world of modern medicine, where drugs prescribed for both sexes often have been tested on male subjects only" (83). Feminist criticism is also concerned with less obvious forms of marginalization such as the exclusion of women writers from the traditional literary canon: "...unless the critical or historical point of view is feminist, there is a tendency to under-represent the contribution of women writers" (Tyson 82-83). Common Space in Feminist Theories Though a number of different approaches exist in feminist criticism, there exist some areas of commonality. This list is excerpted from Tyson: 1. Women are oppressed by patriarchy economically, politically, socially, and psychologically; patriarchal ideology is the primary means by which they are kept so 2. In every domain where patriarchy reigns, woman is other: she is marginalized, defined only by her difference from male norms and values 3. All of western (Anglo-European) civilization is deeply rooted in patriarchal ideology, for example, in the biblical portrayal of Eve as the origin of sin and death in the world 4. While biology determines our sex (male or female), culture determines our gender (masculine or feminine) 5. All feminist activity, including feminist theory and literary criticism, has as its ultimate goal to change the world by prompting gender equality 6. Gender issues play a part in every aspect of human production and experience, including the production and experience of literature, whether we are consciously aware of these issues or not (91). Feminist criticism has, in many ways, followed what some theorists call the three waves of feminism: 1. First Wave Feminism - late 1700s-early 1900's: writers like Mary Wollstonecraft (A Vindication of the Rights of Women, 1792) highlight the inequalities between the sexes. Activists like Susan B. Anthony and Victoria Woodhull contribute to the women's suffrage movement, which leads to National Universal Suffrage in 1920 with the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment 2. Second Wave Feminism - early 1960s-late 1970s: building on more equal working conditions necessary in America during World War II, movements such as the National Organization for Women (NOW), formed in 1966, cohere feminist political activism. Writers like Simone de Beauvoir (Le deuxième sexe, 1972) and Elaine Showalter established the groundwork for the dissemination of feminist theories dove-tailed with the American Civil Rights movement 3. Third Wave Feminism - early 1990s-present: resisting the perceived essentialist (over generalized, over simplified) ideologies and a white, heterosexual, middle class focus of second wave feminism, third wave feminism borrows from post-structural and contemporary gender and race theories (see below) to expand on marginalized populations' experiences. Writers like Alice Walker work to "...reconcile it [feminism] with the concerns of the black community...[and] the survival and wholeness of her people, men and women both, and for the promotion of dialog and community as well as for the valorization of women and of all the varieties of work women perform" (Tyson 97). The following is an annotated version of the fairy tale. I recommend reading the entire story before exploring the annotations, especially if you have not read the tale recently. ONCE upon a time there lived in a certain village a little country girl, the prettiest creature who was ever seen. Her mother was excessively fond of her; and her grandmother doted on her still more. This good woman had a little red1 riding hood made for her. It suited the girl so extremely well that everybody called her Little Red Riding Hood2. One day her mother, having made some cakes, said to her, "Go, my dear, and see how your grandmother is doing3, for I hear she has been very ill. Take her a cake, and this little pot of butter."4 Little Red Riding Hood set out immediately to go to her grandmother, who lived in another village. As she was going through the wood, she met with a wolf,5 who had a very great mind to eat her up, but he dared not, because of some woodcutters working nearby in the forest. He asked her where she was going. The poor child, who did not know that it was dangerous to stay and talk to a wolf, said to him, "I am going to see my grandmother and carry her a cake and a little pot of butter from my mother." "Does she live far off?" said the wolf "Oh I say," answered Little Red Riding Hood; "it is beyond that mill you see there, at the first house in the village." "Well," said the wolf, "and I'll go and see her too. I'll go this way and go you that, and we shall see who will be there first." The wolf ran as fast as he could, taking the shortest path, and the little girl took a roundabout way, entertaining herself by gathering nuts, running after butterflies, and gathering bouquets of little flowers. It was not long before the wolf arrived at the old woman's house. He knocked at the door: tap, tap. "Who's there?" "Your grandchild, Little Red Riding Hood," replied the wolf, counterfeiting her voice; "who has brought you a cake and a little pot of butter sent you by mother." The good grandmother, who was in bed, because she was somewhat ill, cried out, "Pull the bobbin, and the latch will go up." The wolf pulled the bobbin, and the door opened, and then he immediately fell upon the good woman and ate her up in a moment,6 for it been more than three days since he had eaten. He then shut the door and got into the grandmother's bed, expecting Little Red Riding Hood, who came some time afterwards and knocked at the door: tap, tap. "Who's there?" Little Red Riding Hood, hearing the big voice of the wolf, was at first afraid; but believing her grandmother had a cold and was hoarse, answered, "It is your grandchild Little Red Riding Hood, who has brought you a cake and a little pot of butter mother sends you." The wolf cried out to her, softening his voice as much as he could, "Pull the bobbin, and the latch will go up." Little Red Riding Hood pulled the bobbin, and the door opened. The wolf, seeing her come in, said to her, hiding himself under the bedclothes, "Put the cake and the little pot of butter upon the stool, and come get into bed with me."7 Little Red Riding Hood took off her clothes and got into bed. She was greatly amazed to see how her grandmother looked in her nightclothes, and said to her, "Grandmother, what big arms you have!"8 "All the better to hug you with, my dear." "Grandmother, what big legs you have!" "All the better to run with, my child." "Grandmother, what big ears you have!" "All the better to hear with, my child." "Grandmother, what big eyes you have!" "All the better to see with, my child." "Grandmother, what big teeth you have got!" "All the better to eat you up with." And, saying these words, this wicked wolf fell upon Little Red Riding Hood, and ate her all up.9 Moral: Children, especially attractive, well bred young ladies, should never talk to strangers, for if they should do so, they may well provide dinner for a wolf. I say "wolf," but there are various kinds of wolves. There are also those who are charming, quiet, polite, unassuming, complacent, and sweet, who pursue young women at home and in the streets. And unfortunately, it is these gentle wolves who are the most dangerous ones of all. by Charles Perrault Lang, Andrew, ed. "Little Red Riding Hood." The Blue Fairy Book. New York: Dover, 1965. (Original published 1889.) Amazon.com: Buy the book in paperback. Lang's source: Charles Perrault, Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités: Contes de ma mère l'Oye (Paris, 1697). The annotations for the Little Red Riding Hood fairy tale are below. Sources have been cited in parenthetical references, but I have not linked them directly to their full citations which appear on the Little Red Riding Hood Bibliography page. I have provided links back to the Annotated Little Red Riding Hood to facilitate referencing between the notes and the tale. 1. Red: Scarlet or red is a sexually vibrant and suggestive color. At one time, it was not worn by morally upright women thanks to its sinful symbolism. It is also the color of blood with all of its connotations. Perrault introduced the color red to the tale when he first wrote it. Return to place in story. 2. Little Red Riding Hood: The red riding hood is a popular and familiar symbol to much of Europe and North America. In the height of portraiture in the nineteenth century, many young daughters of wealthy families were painted wearing red capes or hoods. Today, some little girls still want to wear red capes for Halloween or other imaginative play. Some scholars, such as Erich Fromm consider the hood to symbolize menustration and the approaching puberty of the young character who wears it. Scholars also debate whether the red garment is a hood or a cap according to the earliest versions which more closely translate from the French and German to "cap." Return to place in story. 3. Go, my dear, and see how your grandmother is doing: In Charles Perrault's version of the tale, the mother simply instructs the young girl to take the items to her grandmother. The Grimms, however, added an admonition from the mother to not stray from the path, adding a moral message to children. Perrault adds the moral to "not talk to strangers" at the end of the tale. Through the moralizing of both Perrault and Grimms', critics explain that the tale moved away from its obvious sexual and horrific tones, to more closely resemble a fable or cautionary tale (Tatar 1992). You can read the Grimms' version here: Little Red Cap. Return to place in story. 4. Cake, and this little pot of butter: These are the food items originally described by Charles Perrault. Later versions have included other food items, most often a bottle of wine. Return to place in story. 5. Wolf: The wolf has become a popular image in fairy tales thanks to this tale and The Tale of the Three Little Pigs. The wolf is a common predator in the forest and thus is a natural choice for the story unlike the witch, ogre or troll found in other tales. The wolf is often a metaphor for a sexually predatory man. The wolf also figures prominently in other parts of British folklore, such as the traditional children's game, "What's the Time, Mr. Wolf?" Return to place in story. 6. Ate her up in a moment: In some versions of the tale, the wolf swallows the grandmother whole, foreshadowing her rescue by a huntsman later. In feminist criticism of the tale, the eating of the grandmother and Little Red Riding Hood is seen as a metaphor for rape. This interpretation has led to the story's frequent reinterpretation by authors, both male and female, in poetry, fiction, and film. Return to place in story. 7. Come get into bed with me: Most of the later versions of the tale omit this element of the story due to its sexual connotations. However, one of the most famous illustrations of the tale by Gustave Dore shows Little Red Riding Hood in bed with the wolf. A study from the illustration is in the upper right hand corner of this page. The full illustration can be seen here Gustave Dore's Little Red Riding Hood. Return to place in story. 8. "Grandmother, what big arms you have!": These exclamations are a favorite story element for tellers and listeners. They are an excellent storybuilding tool, creating anticipation and horror for the listener/reader as Little Red Riding Hood realizes she is not talking to her grandmother. Many oral versions of the story add extra body parts to increase the bawdiness of the story. The list inevitably ends with the teeth however. Marina Warner considers Little Red Riding Hood's initial failure to distinguish the wolf from her grandmother to be a crucial element of the story. She explains that the wolf and the grandmother (as a crone character) are related as forest dwellers needing nourishment (Warner 1994). Return to place in story. 9. Ate her all up: In Perrault's version, Little Red Riding Hood is not rescued but actually dies at the end of the story. The terrifying ending makes the story more realistic and solidifies his advice to not talk to strangers. Bruno Bettelheim is especially critical of Perrault's version since it "deliberately threatens the child with its anxiety-producing ending" (Bettelheim 1976). The Grimms offer a different ending in which a huntsman happens by and rescues the grandmother and Little Red Riding Hood by disemboweling the wolf. The two females escape from the wolf unharmed, like Jonah from the belly of the whale. The huntsman then sews rocks back into the wolf's stomach for punishment. The huntsman in this version represents patriarchal protection and physical superiority. Yet another version of the tale--the French "The Story of Grandmother"--has Little Red Riding Hood rescuing herself. After she is fed a piece of her grandmother by the wolf, she announces that she needs to go to the bathroom. Since this activity is done outside--this is before the common appearance of indoor bathrooms--she goes outside and then runs away. While the interpretations are almost unanimously dismissed today, early scholars considered the tale to symbolize death and rebirth specifically with Little Red Riding Hood as the sun or dawn and the wolf as night (Dundes 1988). Both Roald Dahl's poem of the tale and Stephen Sondheim's musical, Into the Woods, have Red Riding Hood overcome the wolf and later appear wearing a fur coat made of the wolf's fur, instead of the identifying red cloak. But perhaps my favorite version of the tale comes from James Thurber's "The Little Girl and the Wolf." Red Riding Hood is not fooled by the wolf, but takes a gun from her basket and shoots him. Thurber explains, "It is not so easy to fool little girls nowadays as it used to be." You can find full bibliographic references for this short story and the others mentioned in these notes on the Modern Interpretations of Little Red Riding Hood Page.