About-aHUS-EMBARGOED-JUNE-10

advertisement

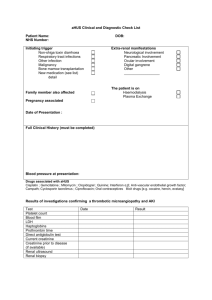

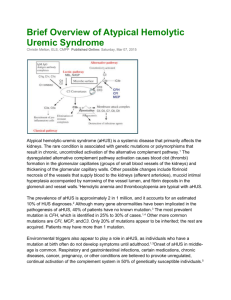

Consumer backgrounder EMBARGOED TUESDAY, JUNE 10, 2014 About atypical Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome (aHUS) About aHUS Atypical Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome (aHUS) is an ultra-rare, life-threatening disease that severely damages vital organs, including the kidneys, heart and brain. 1,2,3 aHUS is caused by chronic, uncontrolled activation of the complement system, (part of the body’s immune system) leading to the formation of micro blood clots in small blood vessels throughout the body. 1,2,3,4 The accumulation of micro blood clots and the associated damage and swelling within small blood vessels is known as thrombotic Blood clots and red blood cells in small blood vessels microangiopathy, ‘TMA’.1,2,3,4 aHUS induced TMA can occur in any part of the body, causing vital organs to fail.5 TMA can also lead to stroke, heart attack, kidney failure and death.1,2,3,4 aHUS can occur at any age; with nearly half all people diagnosed aged 18 and older. This disease is as lifethreatening in adults as it is in children. 2,4,6,7 Between 33 and 40 per cent of people diagnosed with aHUS will die or progress to ESRD following their first clinical manifestation.7,8 10 to 15 per cent of all patients with aHUS die within the first year of diagnosis (mortality in patients within some groups is 19 per cent) and 32 percent die within four years.7 Within one year of diagnosis 64 per cent of patients with aHUS will die, require dialysis or develop permanent kidney damage despite plasma exchange.8,9 In 70 per cent of cases, aHUS is associated with a genetic or acquired abnormality of a part of the immune system known as the ‘complement system’, (30 per cent remain unexplained) which can lead to severe inflammation of the blood vessels and blood clotting that damages the kidneys, causing them to fail.1,4,7,10 Australian aHUS medical registries report a 17 per cent annual mortality rate.11 Prevalence aHUS affects an estimated two in one million people worldwide. Due to the rarity of aHUS, the global incidence is not precisely known.4 It is estimated that between 60 to 70 Australians are living with aHUS.4,12 aHUS and the complement system aHUS is primarily caused by changes in genes that help control and regulate the complement system.1,4,7,10 The complement system is a part of the innate immune system that is “always on” or active. It has the ability to discriminate ‘good’ from ‘bad’ invading organism and to generate a potent ‘first-line’ defence against infections.7,10,13 Damaged red blood cells and clots in small blood vessels 1 In aHUS complement proteins are missing or function poorly and are unable to control the complement system.1 The flaws in complement regulatory genes lead to permanent excessive, chronic and uncontrolled complement activation resulting in TMA and organ damage.1,13 Diagnosis aHUS is a chronic, extremely rare type of TMA and overall awareness of the In patients with aHUS, the body is disease and its natural history has been very limited. Patients with aHUS are unable to control the complement distinct from patients with STEC-HUS, a bacterial-induced (usually Escherichia system. coli) and non life-threatening HUS.8,12 The life-threatening consequences of aHUS make rapid diagnosis critical.8 Clinically acute patients with aHUS induced TMA present to hospital, usually in a critical condition with severe complications including microvascular thrombosis, and multiple end organ involvement.1,4,14 A variety of blood tests and stool samples are used to identify aHUS. Various blood tests can help diagnose the disease or rule out other diseases with similar symptoms.1,4,7,14 aHUS is typically characterized by low red blood cell and platelet counts and kidney or other major organ failures.2,15 Evaluating red blood cells, platelets and creatinine (a sign of kidney function), can assist in confirming an aHUS diagnosis, as well as ruling out STEC-HUS as the cause of the TMA.2,3,4,7,14 Symptoms Understanding aHUS and being able to recognise its signs and symptoms are important steps in managing the disease. Patients with aHUS face a life-long risk of sudden, catastrophic and life-threatening complications due to TMA.2,6,4,7,16 The most common complication of aHUS is kidney impairment affecting up to 100 per cent of patients, often resulting in long-term dialysis and the need for a kidney transplant.2,4,17,18,19 Approximately 48 per cent of patients experience neurological symptoms, including stroke, brain damage and seizures.2,4,17,15,18 Nearly 43 per cent experience cardiovascular symptoms, including heart attack, abnormal blood clotting, blood vessel damage and high blood pressure. 2,4,15,17,18,19 Kidney complications include high levels of creatinine leading to dialysis, transplant, oedema (swelling resulting from fluid retention), and extremely high blood pressure.8 Diarrhoea and other gastrointestinal complications, such as inflammation of the bowel, nausea and vomiting effect 30 per cent of aHUS patients. 2,4,15,17,18,19 Other complications inlcude colon and digestive tract inflammation, lung, liver and pancreatic damage, nausea/vomiting and abdominal pain. 2,4,15,17,18,19 Treatment Until recently, there was little hope of effective treatment for aHUS.2,3,4,6 Current management options for people living with aHUS are limited to supportive care, including plasma exchange and infusion, dialysis and kidney transplantation. These options are clinically inadequate, lifedisrupting and pose significant safety risks to patients.1 Patients who receive kidney transplants face a 50 to 80 per cent risk of losing the transplanted organ within two years due to recurrent disease and therefore, many are not recommended for organ transplant.2,6,7 2 Most aHUS patients who lose permanent kidney function are treated with long-term dialysis, which heightens the likelihood of morbidity and mortality.4 In patients aged 20 to 60 years old, the death rate for those on dialysis increases 20-fold.20 Plasma exchange is only considered to be supportive care, and has not yet been clinically proven to be safe or effective for people living with aHUS. Soliris is the only approved treatment for aHUS addressing the complement dysfunction causing the problem. 2,4,7,14,21,22,23,24 Approval of Soliris® for the treatment of aHUS Soliris® is the first in a new class of treatments that can prevent death and prevent kidney failure in people with aHUS. 3,22,23 Soliris is the only approved treatment for aHUS addressing complement system dysfunction.22,23 Access to Soliris® will give many people living with aHUS the opportunity to receive a life-changing organ transplant, removing the need for dialysis.3,20 The Australian Therapeutics Goods Administration (TGA) approved Soliris® as a safe and effective treatment for aHUS in October 2012. 25,26 Soliris® is the only clinically proven, life-saving treatment indicated for aHUS, and provides a new standard of care for people living with aHUS.3,20,22,23 The cost of Soliris® is currently out of reach for all Australians living with, or caring for someone with aHUS.27 The Life Savings Drugs Program (LSDP) currently funds ten different treatments for seven different rare diseases with costs ranging between $150,000 to $1,000,000 per patient.25 Soliris® is currently funded under the LSDP for paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) another ultra-rare and life-threatening blood disorder affecting an estimated 150 Australians.25 ends # For more information, please contact Kirsten Bruce or Emma Boscheinen from VIVA! Communications on 02 9884 9100 or 0401 717 566 / 0410 630 531. References 1. Noris M, Remuzzi G. Atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009; 361 1676-1687. 2. P. Hirt Minkowski, M. Dickenmann. Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Update on the Complement System and What is New. 3.Scully M, Goodship T. How I treat thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. 2014 January, The British Journal of Haemotology. 4. Loriat, C, Fremeaux-Bachhi V, Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Orphan Journal of Rare Disease 2001;6;120. 5. Sallee M, Daniel, L Piercecchi MD. Myocardial infarction is a complication of factor H-associated atypical HUS. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25 2028–2032. 6. Loirat C, Noris M, Fremeaux-Bacchi V. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23;1957-1972. 7. Noris, M, Caproli, Bresin, E et al. Relative role of genetic complement abnormalities in sporadic and familial aHUS and their impact on clinical phenotype. Clim J am Soc Nephrol 2010;1844-1859. 8. Caprioli J, Noris M, Brioschi S, Pianetti G, et al.Genetics of HUS the impact of MCP, CFH, and IF mutations on clinical presentation, response to treatment, and outcome. Blood 2006 1081267–1279. 9. Brodsky R.A. Clinical Indications for Terminal Complement Inhibition. Johns Hopkins University School ofMedicine2007.http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/hematology/fellows/summer%20course/slides/Brodsky_PN H%20and%20HUS%2007.06.12.pdf. 10. Tsai HM. The molecular biology of thrombotic microangiopathy. Kidney Int 2006 Jul;70(1):16-23 11. Tsai H-M. Pathophysiology of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Int J Hematol. 2010;911-19. 12. Chantal Loirat, Véronique Frémeaux-Bacchi. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011; 6: 60. Published online 2011 September 8. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-60. 3 13. Benzk, Amann K. Thrombotic microangiopathy: new insights. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2010 May; 19(3):242-7. 14. Delmas Y, Loirat C, Muus P, et al. Eculizumab (ECU) in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) patients (pts) with long disease duration and chronic kidney disease (CKD): sustained efficacy at 3 years. Presented at American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Kidney Week 2013, Atlanta, Ga., November 8, 2013. Abstract FR-PO536. 15. M, Remuzzi G. Hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;161035-50. 16. Ohanian M, Cable C, Halka K. Elizumab safely reverse neurologic impairment and eliminates needs for dialysis in serve atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clinical Pharmacology Advances and Applications 20113. 17. Constantinescu A.R., Bitzan M., Weiss L.S., Christen E., Kaplan B.S., Cnaan A. Non-enteropathic hemolytic uremic syndrome causes and short-term course. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43976–982. 18. Neuhaus, T, Calonder S, Leumann, E, P. Heterogeneity of atypical haemolytic uraemic syndromes. Archives of Disease Childhood 1997;76518-521. 19. Dragon-Durey MA, Kumar Sethi S, Bagga A et al. Clinical features of Anti-Factor H Autoantibody-Associated Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 21 2180–2187, 2010. 20. aHUS Action. Atypical Haemolytic Uremic Syndrome: The Experiences of Patients and Families. aHUS Action 2012. 21. Vilalta R, Al-Akash S, Davin J, et al. Eculizumab therapy for pediatric patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: efficacy and safety outcomes of a retrospective study [abstract 1155]. Haematologica. 2012;97(suppl 1):479. 22. Greenbaum LA, Fila M, Tsimaratos M, et al. Eculizumab (ECU) inhibits thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and improves renal function in pediatric atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) patients (pts). Presented at American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Kidney Week 2013, Atlanta, Ga., November 9, 2013. Abstract SA-PO849. 23. Fakhouri F, Hourmant M, Campistol JM, et al. Eculizumab (ECU) inhibits thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and improves renal function in adult patients (pts) with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). Presented at American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Kidney Week 2013, Atlanta, Ga., November 8, 2013. Abstract FROR057. 24. Gaber O, Loirat C, Greenbaum L, et al. Eculizumab (ECU) maintains efficacy in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) patients (pts) with progressing thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA): 3-year (yr) update. Presented at American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Kidney Week 2013, Atlanta, Ga., November 9, 2013. Abstract SA-PO852. 25.Department of Health| Other Supply Arrangements Outside The Pharmaceutical Benefits Sceme. The Life Saving Drugs Program 2014. www.health.gov.au/lsdp. 26. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing: Guidelines for the treatment of Paroxysmal Nocturnal Haemoglobinuria through the Life Saving Drugs Program. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/lsdp-info/$File/pnh-guidelines-june-2013. 27. The aHUS Patient Support Group 2014. http://ahusaustralia.org.au. 4