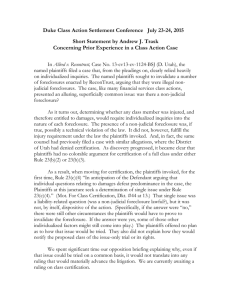

Page Page 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 123743, * 3 of 4 DOCUMENTS

advertisement