S4. Air Quality-Guidelines for methods and results

advertisement

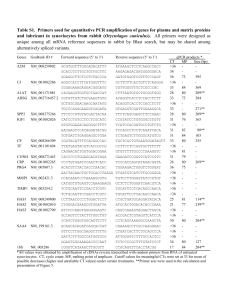

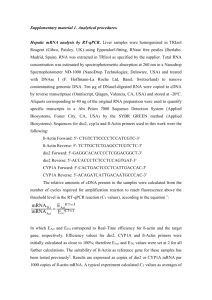

Writing Methods and Results Sections of a Scientific Paper Your assignment You are assigned to write Methods and Results sections in the style of a peer-reviewed scientific paper. You have worked with other people to do your experiment but your write up of your results should be your own work (your own words – not copied from your lab partners). You are obviously expected to share data with your lab partner, but the figures you create and the text you generate should be your own. For examples of scientific papers see the readings for the jigsaw assignment that you did prior to the Daphnia lab. Scientific Papers Writing and reading scientific papers is an acquired skill. Scientific papers are generally organized in a very specific way. They begin with an Abstract, and then have Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion sections. For this assignment you will be writing only the Methods and Results sections, but it might be helpful to have a brief overview of the other sections. Abstract: A very short synopsis of the entire paper. The take home message of each of the other sections of the paper is generally represented in 1 or 2 sentences in an abstract. Introduction: Why we care about the issue and what background information is necessary to understand the topic. Methods: What you did and how you did it. Make sure to include what data analysis you did with your data (ex: We generated summary statistics of gathered data.) Results: What data you collected in the form of written text (describing important observations or results in your data including trends and patterns noticed in your data analyses), a table, graph and/or summary statistics. Discussion: What your results mean in the broader context of the science. What the implications of your experimental results are. Methods In the Methods (sometimes called Materials and Methods) section, you explain how you carried out the experiment. In order for the results of scientific research to be considered reliable, it is important that an experiment be repeatable by other researchers. Keep this concept in mind when you write your Methods. You should give enough detail to allow another person to set up and run the exact same experiment. This will include what equipment you used (and sometimes where you bought it). The Methods section should be a narrative that explains what you did to test your hypothesis. This should include a description of the experiment setup, how the experiment was carried out (i.e. what you did), what kind of measurements or observations you made, and the methods you used to collect and analyze your data. Brief “why” statements can be very helpful in making your methods section clear. For example, “To estimate the Daphnia population...” Also subsection headings within the methods section can help with the organization of this section. Possible subsection headings include “DNA Extraction” or “Data Analysis.” 1 A methods section is not a “how to” guide. It should not be written like a cookbook describing how to do something, it should be written in the past tense describing how things were done in your experiment. Sometimes a figure or table is helpful in describing methods used, such as a sketch of your experimental setup, or a table of volumes added to various vials. If you decide to include a figure or a table, you must reference it in your text. See “Tables and Figures” section below for proper formatting. Give each table or figure a number (in order it is referred to in the text). Results As the name implies, this is the part of your report in which you state your results. It is important that you do not interpret or explain what your results mean in this section (that is what the Discussion section is for). The text of your Results section will essentially be a written guide to your data. It is not necessary to state all of your numeric results – after all, that is what your graphs and tables are for. You should simply point out the highlights of your findings. This may include stating the maximum value, minimum value, significant patterns you see in the data, etc. Consider presenting your data as a chart or a graph. This does not replace having written text in your results; your reader should be able to understand all of the notable information you present without looking at your figures. If you include a chart or graph, be sure to reference it in the text of your paper. It is also good to include any qualitative observations you made while carrying out the experiment. See “Tables and Figures” section below for more details on how to format any tables and figures. Tables and Figures Tables and figures (graphs) should be numbered. Tables should be given one numbering sequence, and figures should be given another sequence. Therefore, if you write a report that includes 2 tables and 4 figures, your tables will be numbered “Table 1” and “Table 2”, and your Figures will be numbered “Figure 1” through “Figure 4.” The order of the tables and figures should match the order in which they are referenced in the text of your paper. Tables Number your tables and include a descriptive title. Below is an example table: Table 1. Cytochrome P4501A (CYP1A) inhibitors used in this study. Compound Abbreviation Alphanaphthoflavone ANF 2 Mechanism of action Partial aryl hydrocarbon antagonist and competitive CYP1A inhibitor Sample references Goujon et al. 1972; Lu et al. 1996 Piperonyl butoxide PBO P450 inhibitor; Binds heme group of P450 Fluoranthene FL Aminoanthracene AA Competitive inhibitor of CYP1A CYP1A inhibitor. Hodgson and Philpot 1974; Miranda et al. 1998 Willett et al. 1998, 2001 Watson et al. 1995 Adapted from Wassenberg and Di Giulio (2004) Figures Label axes on graphs, and include a legend if appropriate. Include a caption explaining your figure with enough detail so that someone glancing at the figure (without reading the text of the paper) can understand what the figure is demonstrating. Below is an example of a figure: 100.00 90.00 80.00 70.00 Percent survival 60.00 0 ng/L 10 ng/L 50.00 100 ng/L 1000 ng/L 40.00 30.00 20.00 10.00 0.00 0.00 10.00 20.00 30.00 40.00 50.00 60.00 Time (hours) Figure 2. Effects of embryonic exposure to various polychlorinated biphenyl 126 (PCB) concentrations on survival of 2-week-old killifish larvae. PCB treatments were for 1 hour beginning at 7 hours post fertilization. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (n=4). 3