Presentation handout 3

advertisement

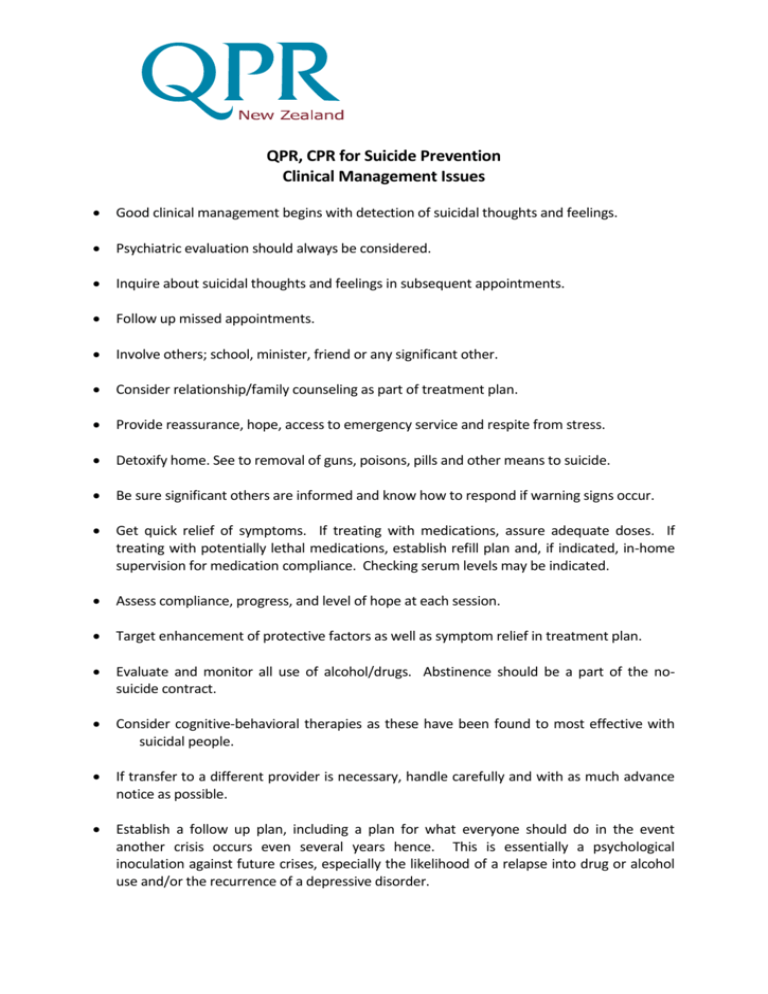

QPR, CPR for Suicide Prevention Clinical Management Issues Good clinical management begins with detection of suicidal thoughts and feelings. Psychiatric evaluation should always be considered. Inquire about suicidal thoughts and feelings in subsequent appointments. Follow up missed appointments. Involve others; school, minister, friend or any significant other. Consider relationship/family counseling as part of treatment plan. Provide reassurance, hope, access to emergency service and respite from stress. Detoxify home. See to removal of guns, poisons, pills and other means to suicide. Be sure significant others are informed and know how to respond if warning signs occur. Get quick relief of symptoms. If treating with medications, assure adequate doses. If treating with potentially lethal medications, establish refill plan and, if indicated, in-home supervision for medication compliance. Checking serum levels may be indicated. Assess compliance, progress, and level of hope at each session. Target enhancement of protective factors as well as symptom relief in treatment plan. Evaluate and monitor all use of alcohol/drugs. Abstinence should be a part of the nosuicide contract. Consider cognitive-behavioral therapies as these have been found to most effective with suicidal people. If transfer to a different provider is necessary, handle carefully and with as much advance notice as possible. Establish a follow up plan, including a plan for what everyone should do in the event another crisis occurs even several years hence. This is essentially a psychological inoculation against future crises, especially the likelihood of a relapse into drug or alcohol use and/or the recurrence of a depressive disorder. QPR, CPR for Suicide Prevention in General Medical Settings Source: Susan J. Blumenthal, M.D. Suicidal behavior is the most common psychiatric emergency. Most general physicians see at least six seriously suicidal people each year; many more will have thoughts and feelings but go undetected. Between 50% and 80% of people who commit suicide have seen a doctor in the weeks to month preceding their death, often using medication prescribed to them. Most suicidal patients are suffering from a psychiatric disorder. Suicidal thoughts and feelings are one of the most common complications of untreated psychiatric illness. In general, psychiatric illness increases the risk of suicide 10 fold. 80% of the time, people experiencing a first psychiatric illness see a general physician, not a mental health professional. It has been estimated that between 25% and 30% of all ambulatory patients in general medicine have a diagnosable psychiatric condition. Including depression, bi-polar illness and schizophrenia, 10% to 20% of all such patients will die by suicide. Only about 10% of suicides have no documentable psychiatric illness. Physicians detect only one in six patients who go on to kill themselves, yet warning signs of suicide crisis are known by others (family members, friends, co-workers, etc.). In one study of practice patterns for suicide risk detection, the odds of being asked if you were having thoughts of suicide by a general physician was one in 20 (these were patients who made a suicide attempt within 60 days of their visit). Even after a psychiatric diagnosis has been made, under treatment of the disorder is common. Untreated depression has been found in 60% of suicides worldwide. The key to suicide prevention is early detection, effective intervention, and aggressive treatment of the underlying condition/situation that is propelling the crisis. Medical Illness and Suicide Chronic medical illnesses are a risk factor suicide, especially ones with a debilitating course. Between 25% and 70% of completed suicides were physically ill at the time of death, with physical illness believed to be a major contributing factor in some 11% to 51% of the cases. Medical illnesses contribute to suicidal behavior in several ways: by precipitating a severe depression making an existing psychiatric illness worse producing an organic mental disorder, impairing judgment. Suicide occurs only rarely in the physically ill where a psychiatric illness is not also present. AIDS, Huntington's chorea, epilepsy, cancer & musculoskeletal disorders have been found to be associated with suicidal behavior. The suicide rate for epileptic patients is four times that of normal controls; in temporal lobe epilepsy the rate is 25 times greater. Secondary depression may be the common pathway. The suicide rate in cancer patients is several times higher than health controls. Risk is highest right after diagnosis and in those receiving chemotherapy. Complicating factors of depression and/or alcohol abuse often cloud the data, especially with, for example, gastrointestinal carcinoma. People with severe and morbid fear of cancer are at elevated risk should they be diagnosed. There is a six fold increase in the rate of suicide among people suffering from Huntington's chorea and in family members not yet suffering overt symptoms of the disease. There is a 10 to 100 times greater risk for suicide in those people undergoing renal dialysis, especially if complicated by depression. Spinal cord injuries, multiple sclerosis, Cushing's disease, thyroid disorders, and other endocrine diseases have been found to be associated with higher rates of suicidal behavior, again probably through the common pathway of co-morbid depression. AIDS victims suffer a 36 times greater incidence of suicide than the general population. Ideation after diagnosis is extremely common. Coupled with a high incidence of depression, dementia and the potential for extreme debilitation preceding death, suicide risk assessment should be routine and monitored over time. Some medications produce depressions and/or diminished judgment, the consequence of which may be suicidal behavior.