On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense

advertisement

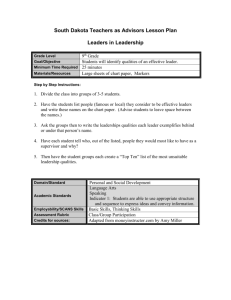

Tyler Tkach 1 Inspiration for Truth and Nietzsche’s Methods Friedrich Nietzsche wrote On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense in 1873. Nietzsche never actually published this piece. It is uncertain as to why, but Maude Marie Clark writer of “Nietzsche on Truth and Philosophy” suggests, he either thought better of the piece; or perhaps for fear of it being misinterpreted. Most scholars including Clark agree Nietzsche’s goal of such a short piece is not to offer criteria for intellect but rather inspire us to question what we think we know. Supported by commonplace views via examples, metaphors, and valid arguments Nietzsche leads us to believe a deceptive sort of intellect as what we mainly desire. Nietzsche’s grounds rely on a higher standard for intellect then what we typically think of for intellect today. His evaluation of partial qualities as skewed qualities is what sets the new standard for intellect. Nietzsche’s proposition on not overlapping reason and desire reveals a similar contrast to the Apollonian and Dionysian tension in Greek mythology. Apollo being the god of the sun is the source of reason. According to Greek mythology, Dionysus the god of ecstasy works best in juxtaposition to Apollo. Our perceptional relationship to things is made possible by the sun. However, the sun doesn’t satisfy our appetites. Both gods play an important role within their own relation to humans. One represents truth and another for pleasures. A brief understanding of these literary figures provides insight as to why Nietzsche evaluates partial qualities as skewed. Nietzsche observed that most are concerned with illusion and beauty causing them to rationalize and accept beliefs according to their desires. Impartial intellect on the other hand is free from illusion. The second group learns directly from first principals in Tyler Tkach 2 order to avoid deception. “He desires the pleasant, life-preserving consequences of truth. He is indifferent toward pure knowledge which has no consequences.” His evaluation of knowledge with partial qualities reveals how common people rationalize beliefs around their wants. Nietzsche’s theory is extremely useful because it sheds insight on the difficult problem of deception and arrogance. This issue shares a commonplace among most audiences. Nietzsche uses a parable to express the destructive nature of combining desire and reason. “There was a star upon which clever beasts invented knowing. That was the most arrogant and mendacious minute of "world history," but nevertheless, it was only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths, the star cooled and congealed, and the clever beasts had to die” This metaphor uses a clever beast to represent the partial knowledge as arrogance, which is soon to be defeated by nature or the truth. Nietzsche’s first reason to explain why most skew concepts with a unification of desire and reason is from what he observed our primary goal for intellect being. He talks about our drive for intellect as not being after truth itself but two other goals. First is the pleasure of believing you know something. The pleasure of skewing beliefs according to Nietzsche via metaphor “The pride connected with knowing and sensing lies like a blinding fog over the eyes and senses of men, thus deceiving them concerning the value of existence. For this pride contains within itself the most flattering estimation of the value of knowing.” Our second drive to intellect is for its usefulness. Our self-interests and reason combined develop useful social strategies as a means of preserving the individual. He projects a commonplace idea of how we muddle up beliefs according to Tyler Tkach 3 place ourselves better within the midst of a disguising culture. The disguises are formed by rationalizing beliefs according to our unification of desires and reason. Both drives for intellect are not after truth. “Deception is the most general effect of such pride, but even its most particular effects contain within themselves something of the same deceitful character.” Nietzsche softens the blow with commonplace appeal by suggesting that “it’s not deception itself we hate but rather what we hate is only sorts of deception.” Mixing emotion into reason isn’t an issue unless there are disruptive or less pleasing consequences. Unifying reason and emotion offer illusion and beauty which provide common men their means for ruling over life. Deceptive intellect is not only “more authoritative and victorious to help one get what he desires” and also helps one disguise, pleasure of intellect. Man strives to exist socially and as long as the consequences of intuitive deception provoke good in some appealing sense he will not to desire Truth. Nietzsche’s defense for this unification being deceptive is based on our selfinterested measure of concepts. The greatest source of our intellect is based on language and “language is a sum of poetically and rhetorically intensified, transferred, and embellished qualities.” He illustrates this idea of what we typically refer to truth as being impartial when instead it’s a skewed interpretation. A stone for instance under man’s measure of all things, exists as something we perceive as hard, yet! The language we use to refer to the qualities of the stone are as if the qualities were something objective to the stone. Tyler Tkach 4 According to Nietzsche, man’s self-interested measure of things causes man’s interpretation of concepts to become deceptive. Our beliefs of what is true based on language are no longer reliable correspondents to truth due to the combination of emotion within the concepts. Nietzsche states “language is built on arbitrary assignments, ideals and metaphors” referring to how man’s assignments are built of relative personal experience. This idea that people mainly concern themselves with skewed terminology was somewhat new for the time. The idea that concepts rely on a partial relationship has grown more accepted with our move to be less dogmatic. Nietzsche’s grounds for impartial qualities as skewed qualities making deception inherent include logical proofs. According to his argument, any concept in the external world that exists, let’s say X. X’s impartial existence exists only as X. However, he emphasizes that human’s perceptions of X is partial due to a personal relationship between X and its perceiver. Human’s perception of X can only be understood through the individual’s relative relationship to X. Therefore, X is up to personal interpretations of how X relates to us individually from the actual world. This relativity in understanding concepts is what makes human’s use of language and subsequently intuitions skewed. Nietzsche’s argument more formally follows: X is only X with all qualities of X, and perceived X are not all qualities of X, perceived X is not X. His second premise would be the stasis for the counterargument. That our perceived relationship to X can assign impartial qualities of X. Human’s relation to X even though it will always be partially individualized doesn’t entail deception. Some beliefs about X’s qualities consistently correspond to X’s actual qualities. Tyler Tkach 5 Nietzsche’s evaluation doesn’t distinguish between relative objective, and relative subjective qualities of objects. Although I agree that perceived qualities can’t form completely impartial concepts. His argument to show our impartial existence to objects would also destroy our knowledge by scientific theories like theories on solar events. Philosophical theories about what knowledge is, are similar to scientific methods where in both cases you have data and theories which explain it by consistently explaining the results of experiments. Nietzsche’s evaluation of intellect recognizes partial rightness as skewed or deceptive. A more sensible view is that relative qualities are not certain but depending on the propositional seeming of the person they can be knowledgeable. If we could make a distinction between each person’s seeming’s of the rock then we could also make a distinction about knowledgeable and ignorant qualities about rocks. The perceived qualities of X are not subjective because both have identical sensations of X. The rock expert has greater experience with rocks so his seemings of qualities of X will differ from Ignorant’s qualities of X. However, we don’t say neither of them knows qualities of rocks because of different interpretations of those definite qualities. This distinction between sensations and the propositional seemings creates our impartiality. Although by distinguishing between a relative objective and a relative subjective qualities of objects some not completely impartial intellects can correspond to truth. Our individual relation to objects simply entails different propositional knowledge of X. Ignorant may only know X is not a tree when looking at the same rock but this different interpretation of X doesn’t make the objective qualities of X change. Tyler Tkach 6 This strategy of evaluating our relationship to the external can make distinctions on our perceived relationship to X. This theory works better than Nietzsche’s with common sense beliefs. Insofar as common sense seemings like tables, trees, and other things generally corresponds to truth. The ‘common sense’ beliefs should correspond to commonly produce seemings which should also correspond to truth. Nietzsche’s theory of abstraction would produce specific beliefs about tables, tree, etc. which aren’t commonly held beliefs. Knowledge, how we use it today does entail truth, but the standard we set on truth differs upon the situation. Nietzsche does not want to say beliefs do not correspond at all but that they include self-interested interpretations. Nietzsche’s conclusion of popular intellect being deceptive is based on how a personal relation to truth can’t assign objective qualities. He deems all qualities subjective because they’re relative and therefore partial. He doesn’t allow people to be epistemically sincere with beliefs because they can’t be completely impartial. This idea adds higher standards for knowledge which doesn’t match the terminology we use today. Standards for truth don’t have to be all-inclusive to communicate actual concepts that do in fact correspond to truth of the matter. This truth of the matter idea is more accepted for discerning the truth or what it means to know propositions particularly. Our personal relations to things are limited, so we offer the best truth of our seeming’s which may differ from more experienced perspectives. The qualities of propositional seemings determine the truth value of our intellect. What we consider knowledge involves some Tyler Tkach 7 self-interest but this partial knowledge doesn’t suggest all theories derived through partial understandings are unreliable correspondents to truth. Distinguishing seemings will position some with greater experience to know more objective concepts than others with identical sensations. To manage our unification of reason and desire in such a way that it is not deceptive would not be to ignore intuitions or what others try to teach us, but instead be responsible by respecting our own as well as others relative experience positioning their seemings with greater propositional knowledge. His argument leads us towards a different means for knowledge which seems now to be dubious. Nietzsche himself may not have believed these arguments to be reason enough to question, but that was not the goal. Ultimately his goal of inspiration of what we think we know is perhaps better expressed through complex proofs which are difficult to prove wrong. I see the purpose of this paper more as inspirational, rather than reasonable. To believe its proof through coherency would be a mistake. However, to serve its purpose understanding its counterargument is all it would take to show how relative humans really are.