The Gettier Problem Ontology - NCOR: National Center for

The Gettier Problem Ontology

Paul Poenicke

This paper is dedicated to explaining the Gettier Problem Ontology (GPO). The scope of the ontology is to represent the subfield of epistemology dedicated to the

development of the Gettier Problem. Gettier’s “Is Justified True Belief

Knowledge?” demonstrated that the traditional concept of knowledge was mistaken.

That is, it was assumed by a number of philosophers—including Plato, A.J. Ayer, and

Roderick Chisholm—that knowledge could be analyzed as having justified true belief as necessary and sufficient conditions. However, through various counterexamples, Gettier and others demonstrated that justified true belief is not sufficient for knowledge.

1.

Background to the Gettier Problem Ontology

How does one go about doing an ontology of philosophy? The challenge is significant for an ontology of philosophy is more than just conceptual analysis of knowledge or the Gettier Problem. An ontology is more than just a bibliographical catalogue, such as Phil Papers, or a structured thesaurus, which defines terms according to the meaning of various terms. An ontology of philosophy ought to do more than simply catalogue the field or provide an exhaustive description of the meaning of philosophical terms. Rather, an ontology of philosophy should explain the structural relations between terms beyond mere meaning. Such an ontology would explain the reference of terms and to connect concepts to reality. This is the unique job of an ontology, particularly discussed by Barry Smith and Pierre Grenon in “Foundations of an Ontology of Philosophy.” The GPO is an extension of Smith and Grenon’s work to provide a clear framework to discuss the variety of entities associated with the philosophical subfield of Gettier Problems and their development.

The guiding principles for GPO inspired by Smith and Grenon include:

Relevance: The GPO represents entities or features of entities which belong exclusively to the selected domain. GPO is not interested in philosophy or even general epistemology. Instead, its domain is the subfield of Gettier Problem

Epistemology, the subfield of Post-Gettier Epistemology that advances and refines the work and themes Gettier uncovered.

Philosophical Neutrality: The GPO represents the field from a theory- neutral perspective. Work associated with the Gettier Problem is rife with dispute. But an ontology of philosophy does not have to resolve philosophical disputes. Rather, it is concerned with what entities there are in the domain of philosophy, and thus, also with what entities philosophical debates are concerned. An ontology of philosophy has to be guided by a principle of neutrality regarding its content in order to make room for all

philosophical views, the latter themselves, together with the associated disputes, being treated as entities in their own right.

Revisability: The GPO is a non-static way of representing the growth of knowledge. The GPO rests on basic distinctions on what all parties agree upon to have a dispute about the Gettier Problem. From this information a basic ontology can be constructed to encourage additional evolution and representation of advances in the field.

2.

A Basic Outline of the GPO

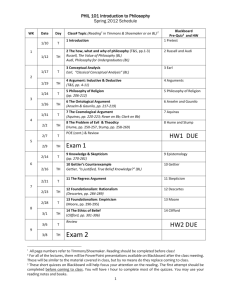

As you can see in this screenshot, the GPO includes occurrents (fields and subfields of philosophy—‘Epistemology,’ ‘Post-Gettier_Epistemologym’

‘Gettier_Problem_Development’), independent continuants (epistemologists, epistemological documents), and dependent continuants (epistemological objects).

Various individuals, particularly papers and authors, are included respectively under the classes of ‘Philosophical Document’ and ‘Epistemologist.’

The subclass ‘Epistemological_Concept’ contains most of the basic ideas related to the Gettier Problem. The GPO briefly defines truth, belief, and justification, along with more technical notions (The KK Thesis, the difference between externalism and

internalism conceptions of justification—points that will be expanded upon later). The

Classic Concept of Knowledge has the necessary and sufficient conditions of truth, justification, and belief—neatly representing the conceptual target of Gettier and types of the Gettier Problem.

The true path rule is followed explicitly in the ontology through:

‘Epistemological_Objects,’ ‘Epistemological_Documents,’ and

‘Epistemologists’ are in the field of ‘Epistemology’ via the is_in_field_of

Object Property relation. (The advancement of the subfield of Gettier

Problem Development is the general aim of the ontology.)

Epistemologists author documents (e.g. “Lehrer authored ‘Knowledge,

Truth, and Evidence.’”). Each epistemologist and document is listed as an individual. The relation between epistemologist and document is via the inverse relations author_of and authored_by. Epistemologists are active in the field of epistemology (represented via the Objet Property

active_in_field), explicate various epistemological concepts (represented via the Object Property explicated_by), and advocate particular theories

(e.g. Ayer, Plato, and Chisholm advocated the Classical Conception of

Knowledge)

for the GPO:

This shot displays that a particular case (Newtonian Physics Case) is an example of the subclass ‘Truth-Based Problem,’ which has the Object

Property of is a type of ‘Gettier_Problem.’ An Annotation Property,

Description_From_Inaugural_Text, provides the case as presented in the document recognized as inducting the case into the field.

Papers present cases; in this instance, “The Analysis of Knowledge” presents the Newtonian Physics Case. This is represented in two ways.

First, each paper is a member of the case-class it is associated with.

Second, each individual paper is associated with the case via the Data

Property inaugurated, which is another way of stating that the document presented a particular case.

See the screenshot below for a summary of the relationship between papers and cases:

3.

Adding to Smith and Grenon through Inauguration and Exemplification

The GPO adds to the work of Smith and Grenon by developing the concepts of inauguration and exemplification. An important aspect of any philosophical field are the papers that inaugurate a particular idea or concept in the philosophical literature. In the

GPO with its heavy emphasis upon the development of various Gettier cases, this is of particular importance. The Annotation Property Description from Inaugural Text incorporates the first presentations of various cases from the actual inaugural text. This ties the ontology even closer to the field it is attempting to represent—a very useful feature of the GPO.

Exemplification is a critical part of the GPO. The key insight of the GPO is that cases exemplify particular subclasses of the Gettier Problem. Various cases illustrate conceptual divisions of Gettier cases, and anyone who has understood correctly each case can reasonably predict how they would be divided. For example, the Chicken Sexer

Case is an instance where a person does not have justification for a true belief: the chicken sexer has true beliefs about the sex of the chicken but has no reason from perception or intuition as to why his belief is justified. This case seems fundamentally different from the Newtonian Physics Case. The Newtonian Physics Case begins by considering that it is intuitively plausible that Newtonian Physics is part of our overall scientific knowledge. But Newtonian Physics is false. So is it possible to know something false after all?

Each of these cases is a Gettier case, an instance where justified true belief is not sufficient for knowledge. Yet each has a unique distinguishing feature: the Chicken

Sexer Case seems problematic because of justification; the Newtonian Physics Case seems problematic because of truth. Thus, it seems that there is a neutral, intuitive method to dividing developments in the field of Gettier Problems. The key to GPO is collating cases and major concepts associated with the Gettier Problem.

The screen shot is the heart of GPO. The various subclasses are collated with a concept that is (1) an agreed upon term related to the Gettier Problem and (2) a central feature of the case in question. Truth, belief, justification—these concepts formed the

foundation for the first subclasses. Associating cases with truth, justification, and belief into various types of Gettier Problems seems to be the easiest, most agreeable way to establish Gettier Problem ontology.

Things became trickier when explicating the ‘Justification-Based Problem’ subclass. Various conceptions of justification have been popular after Gettier’s paper in

1963. Characterizing these various conceptions can be fairly tricky. The standard way to do so is through accepting or rejecting the KK Thesis. As defined by Peter Carruthers, in formal notation the principle can be stated as: "Kp → KKp" (literally: "Knowing p implies the knowing of knowing p"). The KK thesis holds that in order to know something, you must at the same time know that you know it.

1 Internalism and externalism can then be defined through accepting (internalism) or rejecting (externalism) the KK Thesis.

This common distinction between internalist and externalist conceptions of justification unites nicely with luck, the last major term in the Gettier literature to be included in the ontology. Luck is an intuitive part of Gettier cases, instances where punitive knowers gain justified true beliefs based upon some kind of accident or coincidence. Coincidence shouldn’t determine knowledge, as many epistemologists have argued. GPO includes luck only regarding justification. This is not because the GPO does not have space for luck in the ontology; instead, luck is used to differentiate kinds of justification-based problems. (Perhaps the greater inclusion of luck would be an improvement for the next version of GPO.)

Duncan Pritchard’s recent work on luck nicely correlates with the distinction between internalism and externalism based on the KK Thesis. Of the many types of epistemic luck, Pritchard focuses on reflective versus veritistic luck. Reflective luck is associated with internalism: “It is a matter of luck, given what the agent is able to know by reflection alone, that she has knowledge of what she truly believes.” 2 Veritic Luck is associated with externalism: “It is a matter of luck, given that the agent’s belief meets all the relevant epistemic conditions, that the belief is true.” 3

With this distinction in place, it is now possible to turn to the most recent advances associated with the Gettier Problem, what I have described under the subclass

‘Pragmatic_Encroachment_Problem.” The cases in this subclass are still undergoing a good deal of study in experimental philosophy and linguistics. Both the Bank Case and the Knobe Effect Case are associated with situational contexts and the problematic attribution of knowledge based on contextual and pragmatic factors. The Bank Case is associated with predicating knowledge based on situations of high versus low risk, while the Knobe Effect Case associates knowledge predications with various non-epistemic factors (e.g. the drastic impact a negative result can have on whether knowledge is predicated of an individual). The Bank Case and associated cases are at the core of debates over contextualism and the context sensitivity of ‘knows.’ Jason Stanley is one of the many philosophers who has analyzed linguistic data about knowledge attributions and tried to explain why knowledge predications can shift based on context and

1 Carruthers 1992.

2 Pritchard 2004.

3 Ibid.

knowledge attribution (in cases of know-wh versus know-how). The Knobe Effect Case has been a very recent application of the general Knobe Effect to epistemology. James

Beebe, who applied the Knobe Effect to epistemology in 2010, and other experimental philosophers will continue to work on this feature of knowledge associated with the

Gettier Problem.

4.

Future work and Expanding the GPO

While the Gettier Problem is entering its fifth decade, the types of Gettier Cases continue to multiply. How various cases currently subsumed under the

‘Pragmatic_Encroachment_Problem’ subclass will evolve and develop is still unknown.

However, the GPO has based its method on collating cases with accepted concepts and distinctions already utilized in discussions and debates within the subfield of Gettier

Problem Development. I expect the foundation of GPO to remain steady given its already fruitful utility and reliance upon sound ontological principles of relevance, neutrality, and revisability. The representation of GPO may be limited, but its focus is upon critical, central epistemological occurrents and continuants. Such a foundation is responsible practice and has provided a sound ontology of a very confusing field.

Integrating recent work in experimental epistemology would be very helpful to explore Pragmatic Encroachment Problems. However, altering GPO must be done carefully; a firm review of the ontology, removing any errors and adding distinctions of greater centrality, must be done before attempting to make revisions concerning areas already undergoing great revision. Only after the foundation of GPO has been addresses can more information from experimental philosophy be included.

Ideally, the GPO would be expanded to include far more cases and texts than it currently encompasses. Certainly there are different versions of the cases in the subclasses of ‘Truth-Based Problem’ and ‘Belief-Based Problem’—indeed, experimental philosophy may add cases to these seemingly empoverished subclasses. Beyond the inclusion of debates concerning contextualism, the other major area that was left untouched by the GPO was compositional problems associated with the Gettier Problem and attempts to resolve the Problem via changing conditions for knowledge. When

Gettier first offered his paper, philosophers thought that it would be quite easy to resolve the Gettier Problem by adding a fourth condition to the Classic Conception of

Knowledge. Instead, such additivity is difficult to justify, given that many conditions are

“swamped” by truth: a probable or reliable condition for knowledge is simply instrumentally valuable because of its likelihood of associating a belief with truth. One can also ask whether knowledge is more valuable than any than any proper subset of its parts. Additionally, one might wonder why we should attribute significance to a certain value for knowledge over and above the value of this proper subset of conditions for knowledge. All of these concerns are related to the Gettier Problem and part of the subfield of Gettier Problem Development, but could not be integrated into this version of the GPO.

The ultimate goal of the GPO would be to represent the field commenced by the

Gettier Problem so that epistemologists could best understand their field and more efficiently research various questions. The main ontology considered other than that of

Smith and Grenon was the Indiana Philosophy Ontology project (InPhO). Its usefulness as an ontology is extraordinarily limited. It functions extraordinarily well as a hub for hyperlinks to philosophical resources, including the Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy. Below is the screen shot of the ontology’s categorization of the Gettier

Problem ( https://inpho.cogs.indiana.edu/idea/1550).

To say this is a sloppy ontology might be an understatement. The Gettier Problem seems to be a subclass of knowledge, which is a subclass of knowledge and skepticism

(logic of terms problem), and, perhaps, a subclass as well of justification. The merits of

InPhO are significant: there are hyperlinks detailing particular terms and thinkers, making this representational schema potentially very useful. GPO attempted to mimic this utility by including bibliographical information in addition to providing the inaugural representation of various cases. It is this interconnection between web-based utilities and ontology that would greatly enhance GPO and further set it apart as a way of representing the field started by Gettier and developed in his wake.

In conclusion, I believe the GPO is a small but significant advance in representing a significant subfield of philosophy. The range of GPO is certainly less than its scope of representing the Gettier Problem Epistemology. However, the strengths of GPO—its conceptual framework, sensible division of Gettier Problems, correlating cases with various subclass Problems—seems to be a promising way forward for ontologies of philosophy. The GPO would be a great project to publish and encourage institutions like the InPhO to continue. Professionals, graduates, and undergraduates could all benefit from an ontology like GPO, which would hopefully encourage more ontologies of philosophy to support the discipline and philosophical research.

Bibliography:

Ayer, A.J. 1957. The Problem of Knowledge. New York: Penguin Books.

Beebe, J.R., & Buckwalter, W. 2010. “The Epistemic Side-Effect Effect.” Mind & Language, No 25: 474-

98.

Brandom, R. B. 1998. “Insights and Blindspots of Reliabilism.” The Monist, Vol. 81: 371–392.

Carruthers, Peter. 1992. Human Knowledge and Human Nature: A New Introduction to an Ancient

Debate. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chisholm, Roderick. 1957. Perceiving: A Philosophical Study. Cornell, NY: Cornell University Press.

Gettier, Edmund. 1963. “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?” Analysis, Vol. 23: 121–123.

Goldman, A. I. 1967. “A Causal Theory of Knowing,” The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 64, No.12: 357–372.

Goldman, Alvin I. 1976. “Discrimination and Perceptual Knowledge.” The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 73,

No. 20: 771-791.

Harman, Gilbert. 1973. Thought. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press.

Hazlett, A., 2010. “The Myth of Factive Verbs,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 80(3): 497–

522.

Hawthorne. 2003. Knowledge and Lotteries, New York: Oxford University Press.

Ichikawa, Jonathan Jenkins and Steup, Matthias, "The Analysis of Knowledge", The Stanford

Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL =

<http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2013/entries/knowledge-analysis/>.

Lehrer, Keith. 1965. “Knowledge, Truth, and Evidence.” Analysis, Vol. 25, No.5: 168-175.

Putnam, Hillary. 1981. Knowledge, Truth, and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pritchard, Duncan. 2004. “Epistemic Luck.” Journal of Philosophical Research, Vol. 29: 193-222.

Radford, C., 1966. “Knowledge—By Examples,” Analysis 27: 1–11.

Smith and Grenon. 2011. “Foundations of an Ontology of Philosophy.” Synthese, Vol. 182, No.2: 185-204

Steup, Matthias. 2013. "Epistemology", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. URL:

<http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2013/entries/epistemology/>.

Stanley, Jason. 2005. Knowledge and Practical Interests. New York: Oxford University Press.