Horror and Disgust as Gendered Emotional Experience in Dans ma

advertisement

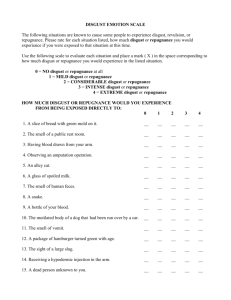

SCSMI Conference 2013, Berlin, June 12-15 Cover sheet Paper title: In Her Skin: Horror and Disgust as Gendered Emotional Experience in Dans ma peau (2002), Martyrs (2008), and Black Swan (2010) Associate professor Rikke Schubart University of Southern Denmark Campusvej 55, 5230 Odense, DK schubart@sdu.dk Bio Rikke Schubart is associate professor at the University of Southern Denmark. She presently works on women, contemporary horror, and emotions. She is the author of Super Bitches and Action Babes: The Female Hero in Popular Cinema, 1970-2006 (2007, McFarland), Mission Complete: The Action Film From Dirty Harry to The Matrix (Med vold og magt, 2002, Rosinante), and co-editor of Eastwood’s Iwo Jima: Critical Engagements With Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima (with A. Gjelsvik, forthcoming Summer 2013, Columbia UP) and War Isn’t Hell, It’s Entertainment: Essays on Visual Media and the Representation of Conflict (2009, McFarland). Paper proposal SCSMI Conference 2013, Berlin, June 12-15 Title In Her Skin: Horror and Disgust as Gendered Emotional Experience in Dans ma peau (2002), Martyrs (2008), and Black Swan (2010) Abstract In the last decade, an increasing number of horror fictions in literature, film, and television features female protagonists, female bodies, and female stories. Psychoanalytical film theory has interpreted the horror genre as oppressing and victimizing women (Clover 1992; Creed 1993). The paper argues that this emerging body of horror expresses – rather than exploits or oppresses – female concerns. Analyzing disgust and female self-injury in Dans ma peau (In My Skin, 2002), Martyrs (2008), and Black Swan (2010), the paper shows how a viewer is invited into an emotional experience that affectively and narratively is constructed as female. Focusing on scenes of cutting and scratching skin, the paper first examines disgust as a primary emotion, next discusses self-injury as evoking moral disgust, and, third, analyzes how a viewer makes sense of self-injury through contrasting emotions of disgust and compassion. Through textual and hermenutical analysis the paper examines disgust in film and in viewer response. The paper combines a cognitive approach to horror emotions (Carroll 1990; Grodal 2009) with recent work in film theory concerned with feeling and affect in horror (Hanich 2010; Laine 2011; Ndalianis 2012). All three films have a protagonist who is a self-injurer and contain explicit and graphic scenes of cutting/scratching skin: In Dans ma peau career woman Esther (Marina de Van) becomes obsessed with cutting and eating her own body. Martyrs is the story of torture-victim Lucie (Mylène Jampanoï) who tracks down the people responsible for her pain. And in Black Swan the dancer Nina (Natalie Portman) struggles with hallucinations when she gets the lead role in Swan Lake. Disgust as primary emotion. Together with fear, cognitive film theory identifies disgust as a core emotion of the horror genre (Carroll 1990; Smith 1999; Grodal 2009). Disgust is one of Robert Plutchik’s primary emotions and is universally shared. It is a defensive and aversive emotion protecting us against corrupt food and contagion (Haidt et. al. 1993) and is concerned with physical well-being. Disgust as moral emotion. Evolutionary psychology suggests disgust has evolved into a “broader disgust” which is socially learned and includes the moral domain. Haidt et. al (1993) examine seven domains of disgust of which “body envelope violations” solicits the strongest response from test subjects. Self-injury belongs to this category. Where disgust protects from physical corruption, moral disgust alerts us to what is morally corrupt. Philosopher Aurel Kolnai says disgust “is at work in creating and sustaining our social and cultural reality . . . it helps us to grasp hierarchies of value to cope with morally sensitive situations, and to maintain cultural order” (Kolnai 2004). The self-injurer’s wounds are not physically contagious and our response of disgust is therefore moral, not primary. Where primary disgust is universal, moral disgust is shaped by culture and, we may add, by class and gender. Kleinhans (2009) writes that “within cultures [disgust] seems to be distinct by class, certainly, and it seems to be inflected by gender and other social variables.” In western culture self-injury is considered “socially unacceptable” by therapists who see it as an illness and a cry for help (“a coping strategy”) (Shaw 2002). That selfinjury is “sick” is underlined by the hallucinations of Esther, Lucie, and Nina. Recently, self-injury has been theorized as a response to inner tension, a message of anger, and an act of resistance to hegemonic ideals of female identity and beauty (Sternudd 2011). Wounds become more than body violations, they are written on a skin that is a communicative medium and a metaphor, a “membrane of separation between subject and object” and “a medium of intersubjective connection” (Laine 2006). To cut or scratch oneself is both a story of despair and of resistance. And to see self-injury performed evokes conflicting emotions in the viewer of disgust and aversion as well as empathy and compassion. Disgust as emotional experience. The last part of the article analyzes how the viewer makes sense of self-injury in the films. Kleinhans divides our response to disgusting things into universal, cultural, and individual. Universal response is innate and linked to primary disgust. Cultural disgust is learned through cultural conventions and is linked to moral disgust. Finally, the individual response of disgust is where each of us draws the line. To “draw the line” is to use the aversive reaction and turn away. To one viewer the self-injury may be only nauseating, to another also beautiful, tragic, or fascinating. The responses – universal, cultural, and individual – interact as a viewer experiences disgust. Laine (2011) calls the viewer’s emotional experience “an emotional dialogue.” It takes place if we accept a film’s invitation to feel and enter a mode of “being-with” the film. As we watch, our experience neither duplicates the emotions depicted in the film, nor does it consist solely of our own emotions. Rather, new emotions emerge in our meeting with the fiction. The dialogue is both affective and cognitive, joining the film’s emotions with ours. In Frijda’s term the experience is situational, that is, appraised and cognitively evaluated in a specific situation. And, as Antonio Damasio (1999) points out, we must experience an emotion to feel it. We cannot describe or analyze an emotion in words before we have felt it. The paper argues that rather than use disgust to merely provoke an aversive reaction, the films invite us to feel protagonists’ pain, read self-injury as a communication of anger, and experience disgust as disrupting and not maintaining cultural order, a disruption which leads to a re-evaluation of moral disgust. The emotional experience is felt as primary disgust, experienced as moral disgust, and evaluated cognitively. What this means in terms of a viewer’s affect, his or her emotions, and his or her appraisals, depends on universal and cultural as well as our individual response. Whether the viewer is male or female, Dans ma peau, Martyrs, and Black Swan invite us to feel like a woman before we draw the line. Bibliography Haidt, Jonathan, Clark McCauley, and Paul Rozin. “Individual Differences in Sensitivity to Disgust: A Scale Sampling Seven Domains of Disgust Elicitors.” Personality and Individual Differences, vol 16, no 5, May 1994: 701-713. Hanich, Julian. Cinematic Emotion in Horror Films and Thrillers: The Aesthetic Paradox of Pleasurable Fear. New York: Routledge, 2010. Kleinhans, Chuck (2009) “Cross-Cultural Disgust: Some Problems in the Analysis of Contemporary Horror Cinema.” Jump Cut, no 51, Spring 2009. Accessed from www.ejumpcut.org on July 2, 2009. Laine, Tarja. Feeling Cinema: Emotional Dynamics in Film Studies. London: Continuum, 2011. Ndalianis, Angela. The Horror Sensorium: Media and the Senses. Jefferson: McFarland, 2012. Shaw, Sarah Naomi. “Shifting Conversations on Girls’ and Women’s Self-Injury: An Analysis of the Clinical Literature in Historical Context.” Feminism and Psychology, vol 12 (2), 2002, 191-219.